Australian aid in the Asian century: part one – the humanitarian case

By Stephen Howes

19 July 2012

Last Wednesday (July 11), I debated Professor Hugh White on whether Australian aid has a future in the Asian century (podcast here). I argued that it did. In this, the first of a three-part series, I start to build the case for Australian aid to Asia.

In this post I make a traditional, humanitarian case for aid that, I argue, is relevant for Asia for at least the next couple of decades.

In the next post, I will argue that aid will remain important and relevant even beyond the next couple of decades, though for different reasons, increasingly to do with our national interest.

Finally, in the third post, I will try to rebut the various arguments made by the detractors of Australian aid to Asia.

My argument for this post is simple: Asia is still full of poor people, poor people matter, and aid in general is of assistance to poor people.

Let me take each of these in turn, starting with the argument that poor people matter. Of course, national interests shape aid programs, and we give aid for a variety of reasons. But we should not, in acknowledging the importance of the national interest, ignore the profound obligation that we have to poor people everywhere.

Whether we have the same obligations to an Indonesian poor person as we do to a poor Australian does not really matter for my argument. All I need is to establish that we have some obligation.

Once that is accepted, and it seems self-evident, then we can move on to the second step of this argument. Of course, it has to be shown that aid does some good. If it does no good, or actually causes harm, then it is not a sensible way to fulfill our obligation to the world’s poor. This is a complex subject, but even the detractors of aid concede that it can help improve education and health outcomes.

Bill Easterly is probably the best-known, certainly the best-informed, aid critic. Even he admits that, and I quote (from his book The White Man’s Burden): “foreign aid likely contributed to some notable successes on a global scale, such as dramatic improvement in health and education indicators in poor countries.” (p. 176) As I have shown in my Economic Record review of Easterly’s book, if we attribute just 10% of the increase in life expectancy in developing countries after World War Two to aid, it comes out at $260 of aid spent for every extra year of life lived as a result. That’s an incredibly cheap price to pay for a year of life: we normally value an extra year of life in a developed country at $100,000 or more.

So, even if we refused to admit that aid did any good outside the areas of health and education (itself an extreme, and unjustifiable position), we would have to admit that aid was in general a high-return investment.

Of course, to say that aid in general does good is not to say that it is the main driver of development. For most countries the main drivers of development success are domestic. But simply to show that there are some forces more important than aid is to say nothing about the effectiveness of aid itself. To argue against aid on these grounds (as many do) is like arguing that because parental love is more important for a child’s development than sporting prowess we should not teach children sport. Those engaged in teaching children sport should not give up because they do not and cannot influence how parents treat their children.

Nor is to say that aid in general does good to deny that some aid is wasted or even does bad. I have invested significant energy myself in criticizing and trying to improve the Australian aid program. But let us not make the best the enemy of the very good.

It is also worth noting that where aid has the most potential to do bad is when countries become aid-dependent. This is where aid can, or at least might, undermine institutions and appreciate the exchange rate. One of the good things about aid to Asia is that Asia doesn’t get much aid relative to the size of the region’s economies, and so these possible negative side effects of aid are unlikely to matter.

It remains only to show that Asia has plenty of poor people.

This is the easiest step of all. There are more poor people in Asia than any other part of the world.

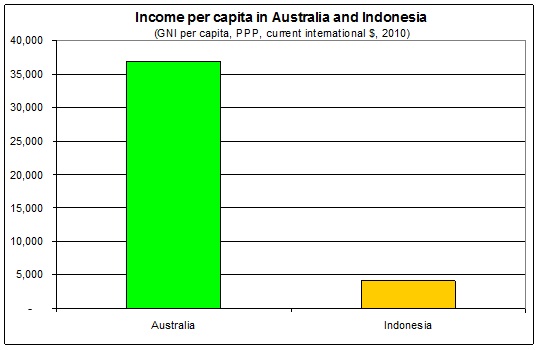

It is in fact almost impossible for us to conceive how poor most Asians are. The graph below reminds us how much richer we are in Australia than, for example, Indonesia. By Australian standards, just about everyone in Indonesia is poor. By Indonesian standards, almost no one in Australia is poor. Half of all Indonesians live in a house without a proper toilet. Half cook on wood or dung. Two-thirds get by without access to clean water.

Source: World dataBank.

Given how poor most Asians are, and how effective aid is on average, one has to only recognize some small obligation to the non-Australian poor to make a compelling argument not just for aid, but for more aid to Asia.

A final point of clarification. To stress this humanitarian obligation is to say nothing about the type of aid we should give. It should not be confined, as is sometimes suggested, to what is often called humanitarian aid, essentially disaster relief. Many types of aid can be effective, and one of the benefits of aid is that it can facilitate innovation and experimentation. In Indonesia, for example, one of most effective aid projects Australia has financed has been to help Indonesia create a large tax payers unit. This has resulted in huge increases of revenue to the Indonesian government, much larger than our aid, collected in a relatively clean, non-corrupt way.

This then is my first argument. Of course, one can go further, and say that if aid helps Asia it also helps Australia. Arguments for aid can certainly be based on our national interest, and indeed I will argue in my next post that this is what will sustain aid in the longer term. But the most obvious and strongest public policy case for aid to Asia at the current time is in terms of it being an effective response to our obligations to Asia’s poor.

In all the talk of the Asian century, it is too easily and often forgotten that emerging Asia is still poor Asia. In our search for new approaches to Asia, it is all too easily and often forgotten that we already have, in aid to Asia, a tool that works. My restating of the traditional case for aid is intended as a reminder of these important facts.

This blog is the first in a three part series on Australian aid in the Asian century. The second and third posts can be found here and here.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.