Australia’s billion-dollar aid cut: Indonesia gets it, or everybody does

By Robin Davies

11 February 2015

As Australia plummets toward the ranks of the least-generous donors, policy choices of unprecedented difficulty must be made about what not to fund. Those who thought that the aid program was at least respectable at A$5 billion per annum, and also many cut-weary people inside the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), might very much prefer not to contemplate the options. But the Development Policy Centre exists in part to provide gratuitous advice on Australian aid policy, and that includes aid-cutting policy. It is the unpleasant duty of this post to contemplate the options.

In what follows, the chosen problem is to identify savings of $1 billion in the 2015-16 aid budget in line with the government’s announced savings objective. The government will also exact savings totaling a further $300 million in the 2016‑17 budget. The latter problem is not addressed here, in part because it is less immediate, and in part because it will likely be achieved by across-the-board cuts. That approach certainly will not work in 2015-16.

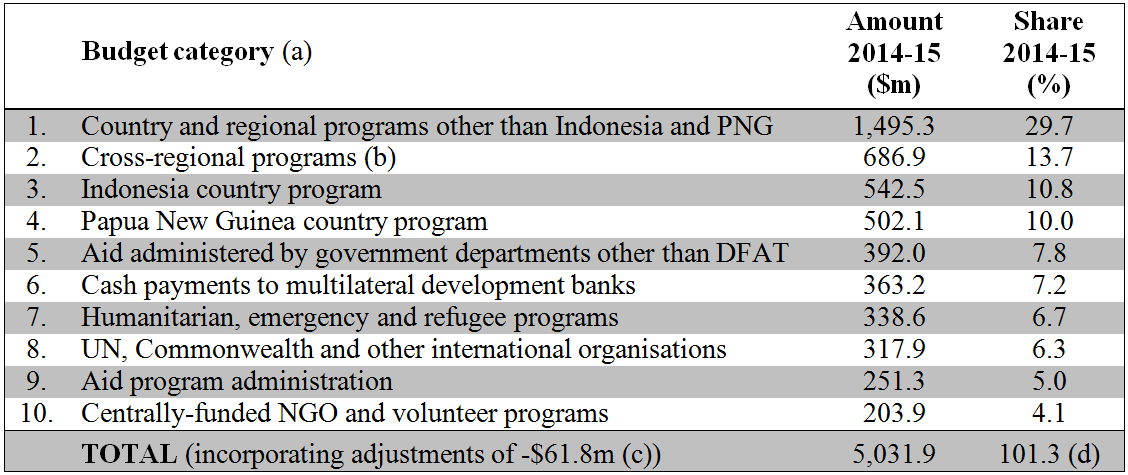

For present purposes, the aid budget can be divided into ten categories of funding, as follows. (Brief explanatory notes are provided at the end of this post.)

Cash payments to multilateral development banks (MDBs) are a no-go area. These payments are made pursuant to legal obligations. The banks hold numerous promissory notes from the Australian government, each of which has an associated draw-down schedule. The timing of payments can be re-negotiated to a degree but the payments must be made. It is not possible to discover what the aggregate cash payment obligation will be in 2015-16 but it does tend to be fairly stable from year to year, so let’s assume it holds steady.

Cash payments to multilateral development banks (MDBs) are a no-go area. These payments are made pursuant to legal obligations. The banks hold numerous promissory notes from the Australian government, each of which has an associated draw-down schedule. The timing of payments can be re-negotiated to a degree but the payments must be made. It is not possible to discover what the aggregate cash payment obligation will be in 2015-16 but it does tend to be fairly stable from year to year, so let’s assume it holds steady.

The budget allocation for humanitarian, emergency and refugee programs was rashly cut in the Coalition’s early-2013 revision of Labor’s 2013-14 budget, then restored in the 2014-15 budget to almost exactly the level previously envisaged by Labor. Labor’s 2013‑14 aid budget was to total $5.6 billion, so Labor was allocating six per cent of it to humanitarian, emergency and refugee programs. This year’s budget is $5 billion, so the Coalition’s restored allocation represented seven per cent of it. One could argue, therefore, that the 2015-16 allocation should be reduced to seven per cent of $4 billion, which is $280 million. However, given the state of the world, the far-reaching impact of the funding provided and the ease of administering it, there is a very strong case for not touching this line.

The allocation for UN, Commonwealth and other international organisations took quite a hit in the last budget, falling from $395 million in the estimated 2013-14 aid budget outcome to $318 million in 2014-15. While commitments to these organisations are in general not legally binding, despite their apparent firmness in so-called ‘partnership agreements’, there would now be little scope to decrease them further. In fact some painful reallocations might need to be made within this allocation to accommodate recent and substantial pledges to the initial capitalization of the Green Climate Fund and to the second replenishment of funding for the Gavi Alliance, as well as commitments [pay wall] to renew funding for medical research into malaria and tuberculosis treatments. This budget line might not be a no-go area, but neither is it a hollow log.

Messing with funding in some of the budget categories above will be fiddly, often diplomatically excruciating, and in many cases only marginally rewarding in savings terms. Nevertheless, some of the savings required will clearly need to be achieved through general shaving. So, for the sake of argument and without endorsing anything that follows, let’s assume a 10 per cent level of savings from the ‘government departments other than DFAT’ category (yielding $39 million), the ‘UN, Commonwealth and other international organisations’ category ($32 million) and the ‘centrally-funded NGO and volunteer programs category’ ($20 million). In addition, let’s assume the current five per cent cap on DFAT’s aid-related departmental expenses as a proportion of total aid is maintained, such that a fall in the aid budget from $5 billion to $4 billion will yield savings of $50 million on the administrative component of the aid budget.

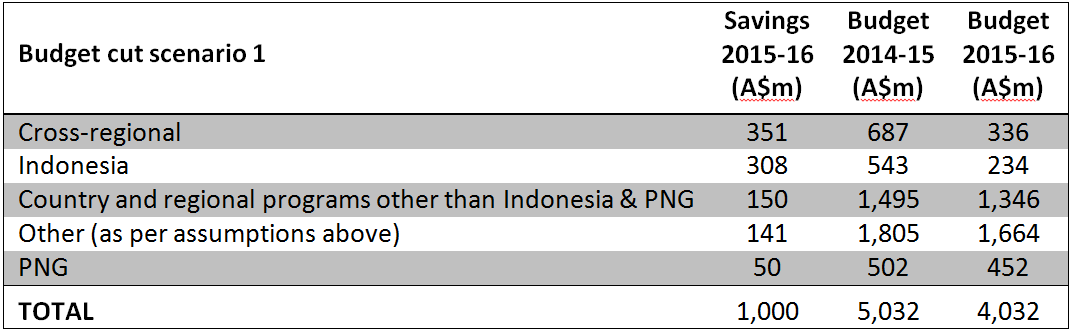

The four assumptions above yield total savings of $141 million in 2015-16, leaving $859 million to be found from the first four of the budget categories above. Together these four categories currently account for 64 per cent of the aid program, or $3.2 billion. Assuming for a moment that the budget cuts could be made in one fell swoop—i.e. that there was total flexibility in all programs funded by the relevant budget lines—one scenario for achieving the required savings is as follows.

This scenario, clearly enough, lands enormous hits on cross-regional programs and Indonesia, while subjecting Papua New Guinea (PNG) and all other country and regional programs to a uniform cut of 10 per cent. (The cut for PNG would preferably be exactly 10 per cent, given the size of this program, while cuts to smaller country and regional programs need not be uniformly applied, provided they yield savings of 10 per cent in aggregate.)

This scenario, clearly enough, lands enormous hits on cross-regional programs and Indonesia, while subjecting Papua New Guinea (PNG) and all other country and regional programs to a uniform cut of 10 per cent. (The cut for PNG would preferably be exactly 10 per cent, given the size of this program, while cuts to smaller country and regional programs need not be uniformly applied, provided they yield savings of 10 per cent in aggregate.)

The cross-regional program, it should be recalled, ballooned from $309 million in the estimated 2013‑14 budget outcome to $686 million in the 2014-15 budget. It is not known what this huge increase was intended to fund, though it is reasonable to assume that part of it was contingency funding for regional resettlement deals, as with Cambodia, and that part of it was meant to cover some of the replenishment costs listed above. Reducing the allocation to $336 million would constitute no cut at all relative to normal levels of funding for this budget line.

As for Indonesia, the size of this country program increased by around 20 per cent after the 2002 Bali bombings, to around $150 million in today’s prices, then almost quadrupled from that base since the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. The first increase was warranted, the second not, or at least not at that magnitude. It is very difficult to maintain that Indonesia, a country whose net aid receipts turned negative for the first time ever in 2013, needs anywhere near $543 million in Australian aid each year. This is arguably the right time to make a step-change in our aid relationship with Indonesia, based on the fact that it is an emerging middle power—a member, with Australia, of the recently formed MIKTA grouping and of the G20 grouping, which has assumed greater significance since being elevated to leaders’ level in 2008. It would be better to cut quickly and cleanly rather than year after year. There is, though, still plenty of work to be done with a budget of over $230 million in Indonesia.

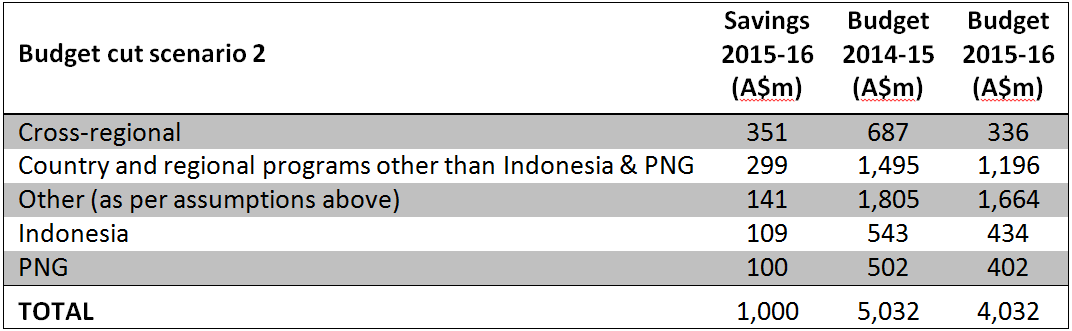

A second, quite different scenario would drop the constraint that limits the impact of the cut on smaller country and regional programs to 10 per cent, while retaining this constraint for less flexible programs (budget lines 5, 8 and 10).

Under this scenario, there is no disproportionate hit on Indonesia. All country and regional programs, including the Indonesia and Papua New Guinea programs, are cut equally by 20 per cent. The cross-regional budget is reduced by $351 million as per scenario 1. The hit on PNG, while not disproportionate, is very large in absolute terms at $100 million.

Under this scenario, there is no disproportionate hit on Indonesia. All country and regional programs, including the Indonesia and Papua New Guinea programs, are cut equally by 20 per cent. The cross-regional budget is reduced by $351 million as per scenario 1. The hit on PNG, while not disproportionate, is very large in absolute terms at $100 million.

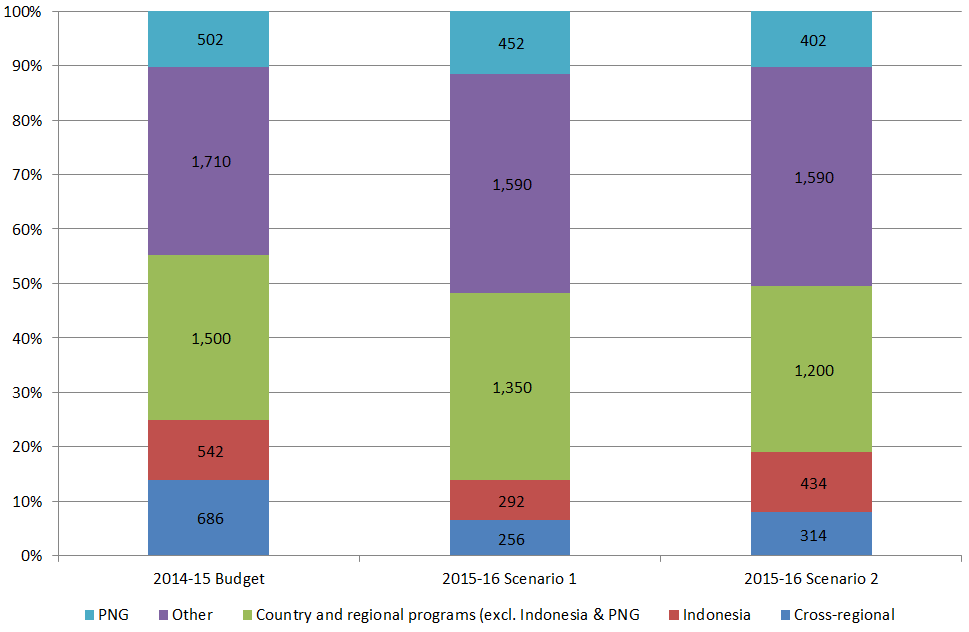

Essentially the two scenarios presented above involve a choice between (i) making a big step-change in aid to Indonesia, with a cut of some 57 per cent, and (ii) cutting all country and regional programs by 20 per cent rather than 10 per cent. The difference between the shape of the aid program now and its shape under both of the two budget cut scenarios is illustrated in the figure below.

Aid budget scenarios compared ($m)

Admittedly, inflexibilities within programs might be such that cuts, wherever they are made, cannot be made in one fell swoop. A pattern of allocations like either of those presented above is very unlikely to be achievable in a single budget. However, as noted earlier, the timing of payments to MDBs is negotiable to some extent, so it may well be possible to move to one of the above patterns over two budgets by adjusting the timing of payments that will fall due in 2015-16.

Admittedly, inflexibilities within programs might be such that cuts, wherever they are made, cannot be made in one fell swoop. A pattern of allocations like either of those presented above is very unlikely to be achievable in a single budget. However, as noted earlier, the timing of payments to MDBs is negotiable to some extent, so it may well be possible to move to one of the above patterns over two budgets by adjusting the timing of payments that will fall due in 2015-16.

Of course, the two scenarios above are drawn from an infinite universe of possibilities. Nevertheless, they illustrate the fundamental choice that the Minister for Foreign Affairs faces, given that she cannot extract large savings from programs other than country and regional programs, and in some cases should not do so anyway. So, which way should she jump?

My vote goes to scenario 1. As argued above, Indonesia can well use a substantial allocation but does not need to consume over 10 per cent of Australia’s aid, or over one-fifth of Australia’s aid through country and regional programs. And aid to PNG should not be reduced much given that country’s woeful development indicators and narrow donor base—though it would be a fine thing to see this part of the aid budget more effectively used.

Nothing in what is said above is based on pragmatic considerations, and certainly not on any assessment of diplomatic feasibility. However, it should be possible to communicate a step-down in aid to Indonesia as quite a deliberate correction now that the tsunami is far behind us and Indonesia is increasingly playing a middle-power role internationally. There is of course a large danger that a cut in aid to Indonesia this year, of any magnitude, will be perceived, or indeed presented, as a retaliation for the (now seemingly imminent) execution of two Australian citizens. But aid to Indonesia can hardly escape a substantial reduction under any scenario.

Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre. He serves on the board of an NGO which has received funding from the Australian aid program, and the Centre itself also receives funding from the aid program.

Notes to budget categories table: (a) Figures are drawn from Table 1 of the DFAT publication ‘The 2014-15 development assistance budget: a summary’, in which allocations to countries and regions reflect DFAT country program budgets, not ‘total flows’ estimates as in Table 2 of the same publication. (b) The cross-regional allocation funds programs that benefit multiple regions, such as sector-based initiatives, but also functions as a war chest in which to park funds that the government does not wish to allocate to programs at budget time. (c) The negative adjustments are not explained in the 2014-15 budget papers but are of a similar magnitude to those made in previous years, which were said to be required to exclude some expenditure not eligible to be reported as Official Development Assistance, like GST payments, and reconcile expenses calculated on an accruals basis with cash payments. (d) This total adds to more than 100 per cent owing to the application of the adjustments described in note (c).

About the author/s

Robin Davies

Robin Davies is an Honorary Professor at the ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy and an editor of the Devpolicy Blog. He headed the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security and later the Global Health Division at Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) from 2017 until early 2023 and worked in senior roles at AusAID until 2012, with postings in Paris and Jakarta. From 2013 to 2017, he was the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.