DFAT’s country programs bore the brunt of the 20% aid cuts implemented in last week’s budget. The reduction in country programs accounted for almost two-thirds of all cuts.

DFAT’s country programs bore the brunt of the 20% aid cuts implemented in last week’s budget. The reduction in country programs accounted for almost two-thirds of all cuts.

As Matthew Dornan pointed out, the methodology of enacting the largest single year cut ever to Australia’s country and regional aid programs was pretty clear: protect the Pacific, cut Asia (almost) across the board by 40%, and eliminate (or significantly wind down) aid to countries in regions outside of our sphere of influence. But country and regional programs make up only half of the total aid spend. This blog aims to complement Matthew’s country allocation blog, with a similar piece on the ‘non-country’ side of the aid budget. We also draw on a number of insights from Robin Davies’ post-budget blog.

We are interested in who, apart from various countries, are the ‘losers’ and ‘non-losers’ of this budget (to quote a phrase from Devpolicy’s aid budget breakfast). If you don’t have time to read it, in brief, the non-losers are: humanitarian; NGOs; the multilaterals; and other government departments. The losers are: the UN and volunteers. Sectoral funds are a mix of non-losers and losers. And we do find one winner in all the carnage: DFAT.

Table 1 shows the division of the aid program into country and regional programs and everything else. You have to go back to the mid-2000s to find a time when country programs was less than one half of the aid program, as it now is.

Table 1 Australia’s aid: country programs and everything else (current A$ ‘000)

Notes: The small Direct Aid Program ($22 million) – administered by Ambassadors in each aid-recipient country, and which has not been cut – is included under country and regional programs. Cash payments to multilaterals fluctuate year to year (see text below). Table modified from this blog.

Notes: The small Direct Aid Program ($22 million) – administered by Ambassadors in each aid-recipient country, and which has not been cut – is included under country and regional programs. Cash payments to multilaterals fluctuate year to year (see text below). Table modified from this blog.

Source: DFAT budget documents. Underlying data and working available here.

Let’s go through the ‘everything else’ items one by one, in the order of the table. The humanitarian (disaster relief) budget is a clear ‘non-loser.’ This is welcome; the world is facing a humanitarian crisis, and the discretionary funds in the humanitarian aid budget are often the first areas to be put on the chopping block in an aid program facing budget pressure.

Our prior commitments to multilateral replenishments (mainly for the World Bank and ADB) are also safe from cuts and are unlikely to be affected until multilateral replenishments crop up again. The amounts paid vary from year due to the nature of the multiyear commitment ended into. We have been told all commitments will be honoured, and the variation – actually an increase – simply reflects natural variability. There was no mention of the government’s commitment to joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. This will be taken from the aid budget at some stage, but likely not until next year at the earliest. It also appears that the AIIB will have no concessional arm, so there will be no replenishment processes or contributions to the scale of those to the World Bank’s IDA or Asian Development Bank’s AsDB.

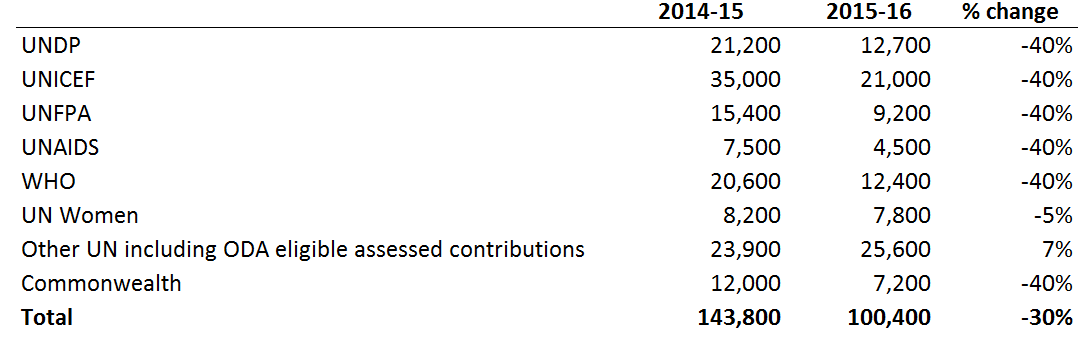

The UN has not been as lucky with only UN Women (receiving a 5% cut) being spared from a 40% across the board reduction (Table 2). The much maligned (and poorly ranked) Commonwealth Organisations have also received an overdue 40% haircut.

Table 2 UN and Commonwealth funding (current A$ ‘000)

Then there are all the sectoral funds and programs, which present a mixed picture. First, a word of definition. This spending is only a small minority of total sectoral spending: it captures funds dedicated to a sector but not a country; for example, funding for GAVI or Transparency International. In a positive move for a budget that has largely taken a step back in aid transparency (no forward estimates in the central budget documents, no updated estimates of 2014-15 spending, no breakdown of funding to other government departments, and no ‘Blue Book’), the budget highlights page does break down what it calls ‘cross regional programs’ into new levels of detail.

Then there are all the sectoral funds and programs, which present a mixed picture. First, a word of definition. This spending is only a small minority of total sectoral spending: it captures funds dedicated to a sector but not a country; for example, funding for GAVI or Transparency International. In a positive move for a budget that has largely taken a step back in aid transparency (no forward estimates in the central budget documents, no updated estimates of 2014-15 spending, no breakdown of funding to other government departments, and no ‘Blue Book’), the budget highlights page does break down what it calls ‘cross regional programs’ into new levels of detail.

Table 3 shows the available data on sectoral funds and programs. The first part of the table shows those areas where large, ‘round number’ cuts are made. The second part shows where cuts have not been made.

If you look at the entries in the second part, it looks like we are cutting funding to global health (Global Fund, GAVI), education (Global Partnership for Education) and climate change (Green Climate Fund). However, we have been assured that in fact this just shows the lumpy and uneven nature of these commitments, with some of the payments due from us in fact brought forward to this year.

In summary, where relatively recent commitments have been made to relatively high-profile global groups with relatively strong support, cuts have not been made: that protects health, education and climate change. Gender and innovation are spared as priorities of this government, as well as disability. We were also told the recent commitments to medical research would not be affected. Everything else gets cut: from governance to infrastructure to sanitation.

Table 3 Sectoral funds and programs (current A$ ‘000)

Note: Global health, education and climate fund commitments have not actually been cut. See text above table for discussion.

Note: Global health, education and climate fund commitments have not actually been cut. See text above table for discussion.

NGOs will be breathing a sigh of relief – they too are among the ‘non-losers’, with just a 5% cut to the ANCP. Australian development NGOs have become very reliant on the ANCP in recent years. Volunteers, however, are not so lucky, as the Australian Volunteer Program will be forced to downsize by 30%. This will likely result in a double impact on organisations within many developing countries, who will be left with a smaller pool of free labour on top of the funding cuts already coming their way.

Funding to other Government Departments has also been reduced, but only by 14%, making them (perhaps just) a non-loser in aggregate. Information on which government departments will get how much aid was unfortunately missing. The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), referred to by Minister Bishop as the ‘diamond in the DFAT crown’, was interestingly left out as a separate line of reporting for the first time, but as noted by Robin Davies only took a 5% reduction.

Given that the aid program’s operational budget has shrunk by 20%, and the Government’s decision last year to restrict aid running costs to 5% of total ODA, many expected that there would be another round of retrenchment this year. Not so. Departmental funding remains unchanged from last year’s budget. Perhaps implementing the cuts will be labour intensive, but that will be done in the first half of the year. The ratio of running costs to total ODA this year is in fact, at 6%, equal second highest ever. The only year it was higher (7%, in 2013-14) there were at least the arguments: (a) that staff had been expanded in preparation for a further increase in aid and (b) that the aid budget was unexpectedly cut in the second half of the year. Running costs are almost twice as high as the last time aid was at around the $4 billion mark, back in 2007-08 (adjusting for inflation of course).

Figure 1 DFAT departmental spending

Keeping running costs fixed in nominal terms might look like a ‘non-losing’ outcome rather than a winning one, but the fact that there will be no reduction in aid staff, despite the biggest aid cut ever, suggests that DFAT in fact emerges as the only winner from last week’s aid budget.

Keeping running costs fixed in nominal terms might look like a ‘non-losing’ outcome rather than a winning one, but the fact that there will be no reduction in aid staff, despite the biggest aid cut ever, suggests that DFAT in fact emerges as the only winner from last week’s aid budget.

The other big surprise is that, as Jacqui De Lacy commented in her budget breakfast remarks, on the whole the cuts to the non-country part of the aid program weren’t more severe. As Jacqui noted, one would have expected a government with a strong focus on economic diplomacy, branding and the national interest to put country programs first not last. The explanation is in at least part luck. The Global Fund, GAVI and the World Bank all had replenishments and pledging rounds in the last year or so, before these massive cuts were announced, and Australia made commitments then more or less in line with earlier contributions. In a sense, they got through the door before it was closed. The real test for them will come in two or three years time, when the next pledging and replenishment rounds come around.

Jonathan Pryke and Camilla Burkot are Research Officers at the Development Policy Centre. Stephen Howes is Director of the Centre.

Thank you all for this useful summary. I’m glad that DFAT aid staffing has not been cut at this stage as it will require significant staffing numbers and skilled staff to ensure that the massive cuts within countries preserve the most effective poverty reduction programs.