Budget support: past allocations and future prospects

By Susan Dodsworth

25 August 2014

Budget support has become a prominent part of the aid effectiveness agenda. This form of aid is given directly to recipients, who take responsibility for financial management and implementation. This trades-off a reduction in donors’ control of aid for an increase in recipients’ ownership of development programs. In this context decisions about who should get budget support, and how much, are critical.

Understanding the allocation of budget support

Most research on the allocation of aid budget support employs quantitative methods. This sometimes makes it difficult to interpret results or to examine the impact of variables for which there is no readily available data. In a paper presented at the Australasian Aid and Development Policy Workshop 2014, I tried to fill this gap, using mixed methods to examine the allocation of budget support by bilateral donors.

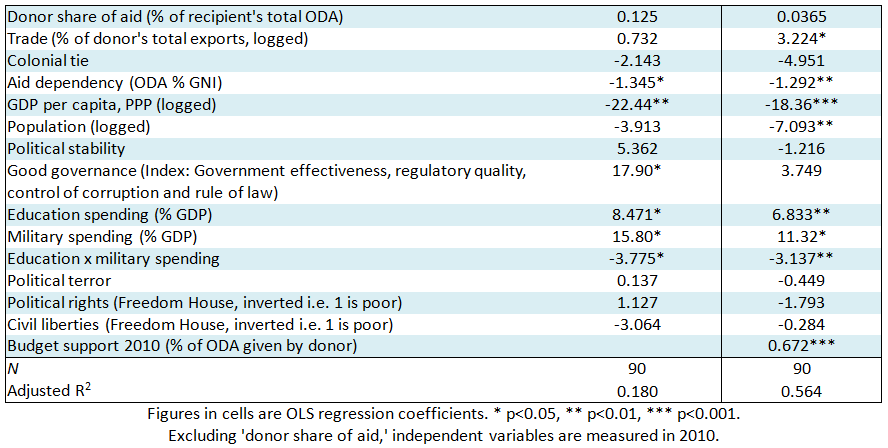

The quantitative component of the paper, partially summarized in Table 1 (available at the end of the post), led to two key findings. First, bilateral donors allocate budget support in a manner generally consistent with their policies. Pro-poor spending and good governance attract budget support, but their effect is not large, nor always significant. Absolute levels of human rights and democracy have little effect on allocations, though this may be because donors care more about trends over time. Second, allocations of budget support are characterized by a significant degree of stability. Donors’ decisions about whether or not to use budget support in a particular country, and to a lesser extent their decisions about how much budget support to allocate, are strongly influenced by whether budget support was provided, and how much, in the previous year. This may reflect the fact that many variables change little from year to year. It may also be the product of what others (such as Carey) have termed ‘bureaucratic inertia’.

The qualitative evidence (which came from a series of interviews conducted in Zambia and Uganda in 2013 and 2014) provides two further insights.

The donor matters

Interviewees consistently emphasized the role of ‘donor side’ variables that are not commonly included in statistical models of aid allocation. These included:

- interactions between public support for aid in the donor country, the economic situation of the donor; and the extent of media coverage of scandals and crises (particularly those relating to corruption) in recipient countries.

- donors’ desire to buy a seat at the table, i.e. the high level policy dialogues that are associated with budget support.

The interdependence of donor decisions

Interviewees made it clear that decisions about budget support are not made in a vacuum; the decisions of other donors matter. This was particularly true of decisions to suspend budget support in response to corruption. This may be an indication that efforts to co-ordinate donor actions, such as the GOVNET Framework for Collective Responses to Corruption, are working (detail available here [pdf]).

Ultimately, the evidence indicates that while donors tend to abide by their own policies, those policies are only part of the picture. Several factors not mentioned in policies have an important influence on the allocation of budget support. In some cases, these appear to be more influential than factors such as good governance, pro-poor policies, and respect for human rights. As disillusionment with budget support grows, fueled by disappointing returns in terms of governance and political reform, perhaps we should be asking whether the problem is the modality, or the manner in which it is allocated

The future of budget support

Until relatively recently budget support was a popular aid modality with donors, particularly multilateral and progressive bilateral donors. This appears to be changing, despite the fact that many (if not most) evaluations of budget support have been cautiously positive (such as this one). The Netherlands, for example, curtailed the use of budget support in 2010 because of doubts about its effectiveness (see this report [pdf]). They are not alone. As Figure 1 shows, allocations of budget support appear to have peaked in 2010, and are now in decline. Total aid allocations have been relatively stable in this period.

Figure 1: Budget support to all developing countries, 2006-2012

Source: OECD, International Development Statistics (available here).

Source: OECD, International Development Statistics (available here).

In recent interviews conducted in Malawi, Zambia and Uganda, donor agency staff overwhelmingly reported negative attitudes towards budget support. Some went so far as to describe budget support, and in particular general budget support, as ‘dead or dying’. This begs the question: does budget support have a future?

Three main factors cast doubt on the future of budget support:

It’s politically unpopular

In the current era of fiscal austerity, aid has become harder to justify and donors are becoming more risk averse. This bodes ill for budget support; even its proponents admit that it’s a high risk modality. The impact of this is magnified by the fact that budget support can’t be directed towards donor country NGOs or credited with specific, easily explainable outputs.

Corruption

Corruption scandals have led donors to freeze, and in some cases cancel, budget support. Recent examples include Cashgate in Malawi, and a scandal at Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister (OPM). Budget support is high profile and perceived as more vulnerable to corruption. Regardless of whether it was actually the problem, it tends to be cut when donors want to send a signal to recipients.

Frustration among recipients

Budget support was supposed to be a reliable and predictable modality that reduced fragmentation and streamlined administration. In practice, recipients face complex performance assessment frameworks and donors who are increasingly willing to suspend or delay disbursements. A surprising number of officials within Ministries of Finance are waxing nostalgic for the era of projects.

Three different considerations suggest that budget support may still have a future.

It buys a seat at the table

Budget support is commonly tied to high level policy dialogues between donors and recipients. Whether these have real influence on recipients is debatable, but they remain a significant consideration for donors, especially those with smaller portfolios.

There’s no clear evidence that budget support increases corruption

A link between budget support and corruption has not been clearly demonstrated. In fact, some of the scandals that have led donors to freeze budget support have been the product of project-era legacies. Following Uganda’s OPM scandal, the Auditor-General documented how old project bank accounts were used to divert aid from its intended purpose.

What’s the alternative?

No-one has come up with a good replacement for budget support. Most donors are attempting to tie budget support more closely to results. Some are re-routing aid through other modalities, primarily projects. But there are limits to the feasibility and desirability of this option; the short-comings of projects are well known.

While budget support is likely to survive, who uses it, and how, is shifting. General budget support, already dominated by multilateral donors, may be abandoned by bilaterals, who see sectoral budget support as easier to justify politically and less susceptible to corruption. Donors are also re-emphasizing the importance of good governance. Whether this can fix the short-comings of budget support remains unclear. Good governance is often equated with public financial management. This technocratic approach allows it to be cast as apolitical, but risks conflating accountability with accounting. If good governance is to save budget support, an approach that recognizes its political dimensions may be required.

Susan Dodsworth is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political Science, McGill University.

Table 1: Proportion of Official Development Assistance (ODA) provided as budget support, 2011

About the author/s

Susan Dodsworth

Susan Dodsworth is a Research Fellow at the International Development Department of the University of Birmingham. Since January 2016, she has been working on the Political Economy of Democracy Promotion Project, co-authoring a number of policy papers on parliamentary strengthening, political party assistance and civil society support. Her research interests include comparative democratisation, the politics of international development, and the interaction of state-capacity and democracy.