RAMSI, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, is the regional policing, peace-keeping and development mission that arrived in Solomon Islands (SI) in 2003 in response to the country’s civil conflict. Nominally it has involved contributions from 15 Pacific countries. In practice, material input has predominantly come from Australia and, to a lesser extent, New Zealand.

2013 marked the tenth anniversary of RAMSI. It was also a year of transition, in which the military component of RAMSI was concluded, and its development functions spun off to bilateral aid programs. RAMSI has thus shrunk to primarily a policing mission.

Last year, we ran a number of blog posts to mark the tenth anniversary of RAMSI. The series ran to 13 articles, and was testimony to the power of expert crowd-sourcing. We received a fascinating range of views making a collection that deserved to be put together – which we have, in this volume [pdf].

Our contributors included the (then) outgoing RAMSI Special Coordinator alongside a range of commentators whose research-related and/or practical experience afforded them insight into RAMSI and Solomon Islands more generally. Several contributors came from within Solomon Islands civil society. Two were expats who have spent much of their lives in the country. Some were integrally involved in peace-building efforts during the Tensions, and all have interacted with RAMSI in a range of ways.

We gave very little guidance to our authors, except to ask them to reflect on RAMSI, and/or Solomon Islands more generally. To disentangle the various views we got, we have grouped the answers we received as if they were responses to one or more of three questions.

- Has Solomon Islands progressed or regressed over the last decade, or both in different ways?

- What have been the strengths and weaknesses of RAMSI?

- What could and should have RAMSI done differently?

In the introduction to the volume, we summarize the views of our various authors in relation to each of these questions. We don’t situate every author in relation to every question, but rather discuss each contribution where we think it fits best.

1. Has Solomon Islands progressed or regressed over the last decade, or both in different ways?

In his post, the first in our series, Nicholas Coppel, then the RAMSI Head, emphasizes the progress Solomon Islands has made: “Security has improved, services are being delivered and the economy is growing.” Coppell also draws attention to a number of SI institutions strengthened by RAMSI, and to improved public finance responses. As the volume shows, each of these claims is contentious, at least as full assessments.

Most other authors are far less positive. On the security front, all would agree that security is now better than ten years ago, but several argue that the country still faces real risks. Ashley Wickham argues that we should “expect further turbulence.” Benjamin Malao Afuga notes that “development conflict” remains a threat. Louise Vella, in her moving account of the reconciliation process, notes that much more needs to be done to build a “durable peace” because “the grievances that lead to the conflict remain”.

Coppel’s claim that “services are being delivered” is supported by survey statistics cited by Clive More that show increased satisfaction with health and police services. But Benjamin Malao Afuga adds a reality check by noting the simple and inarguable point that, “[m]any Solomon Islanders still do not receive the services they need.”

The economy is certainly growing, but Shahar Hameiri highlights what he calls the “inconvenient truth” that the higher growth is largely due to higher, and more unsustainable than ever, levels of logging. Hameiri writes:

..the RAMSI-era has seen a logging boom so big that logged timber volumes have reached extraordinary levels of six to eight times the estimated sustainable yield of 250,000 cubic metres per annum – more than double the previous logging boom of the 1990s.

The legacy of the logging boom, once it is over, will be minimal, Hamieri argues. Graham Baines concurs that “the over-exploitation of the forests has been a long-term economic disaster.” And, indeed, the IMF August 2013 SI country report shows that logging production has already started to fall. However, both Graham Baines and Benjamin Malao Afuga both take a broader, and therefore more optimistic, view, noting the importance of the fact that “investor confidence has returned over the last ten years.” (Baines)

Whether this confidence will lead to growth beyond logging remains to be seen. Matthew Allen and Sinclair Dinnen raise the possibility of a transition from logging to mining, noting that the Gold Ridge mine has re-opened, and that “there is mineral prospecting and mine lease conversion taking place throughout the archipelago.” Allen and Dinnen are appropriately cautious, however, about the welfare implications of any such shift.

What about governance, Coppel’s fourth area of progress? The title of Tony Hughes post – “Solomons saved from sinking, but drifting and taking in water”— tells us that he has a very different view. Transform Aqorau shares Hughes’ perspective: according to him, SI is “falling down in bits and pieces.” He acknowledges some institutional improvements, but argues that: “no one in 2003 could have foreshadowed that, by 2013, corruption would have become so invasive in Solomon Islands …”

Joseph Foukona provides a very valuable contribution by focusing on recent policing developments, which call into question the sustainability of any RAMSI-backed improvements. The acceptance by the police of funding from a Honiara MP to travel to Vanuatu for a soccer tournament and the reinstatement of a deputy police commissioner prior to investigations into allegations against him for malpractice “bring into question the professionalism and impartiality of the RSIP,” as well as its independence.

Terence Wood is somewhat more optimistic, pointing to positive trends such as an increasingly active urban civil society, though even he concludes that prosperity and stability will only be secured if the country sees “the rise of national political movements” to counter the country’s strongly clientelist politics.

Also on governance, Matthew Allen and Sinclair Dinnen point to the rise of constituency funds in Solomon Islands. More generally, Ashley Wickham pins the blame for the country’s ongoing problems on the country’s political culture, as do Terence Wood and Graham Baines. In the words of Wickham:

… many people, including national leaders, see government as a garden of opportunities to harvest as they see beneficial for themselves and their voters. And the country wants a majority of visionary and courageous leaders to provide the space, the resources and the authority to effect change.

2. What have been the strengths and weaknesses of RAMSI?

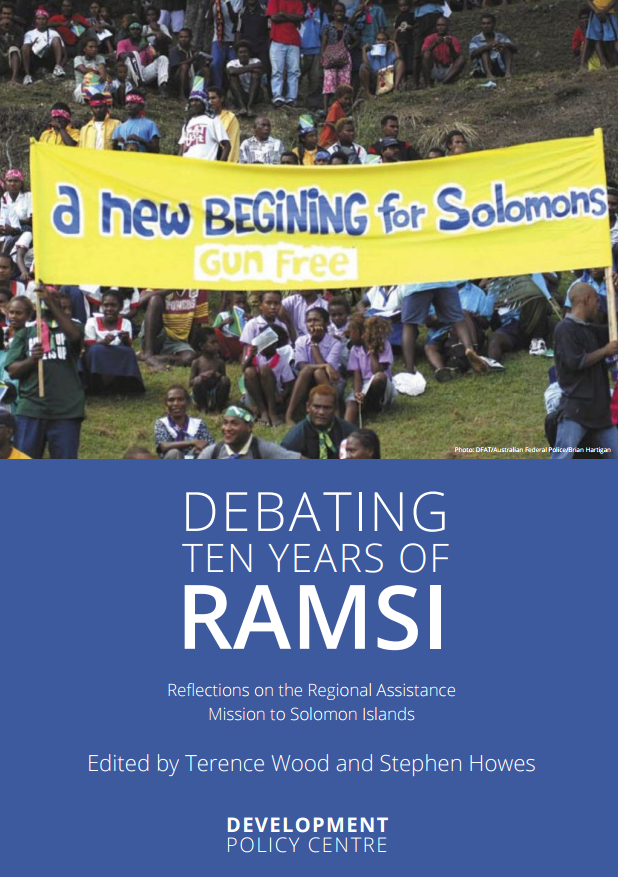

Tony Hughes nicely highlights the very limited consensus around this question. The “only thing” that all assessors agree on “is that getting the guns off the streets of Honiara and the rural roads of Malaita and Guadalcanal in 2002 was essential, and was well done.” Though it was notched up very quickly, mostly within a few weeks of arrival, it was no mean achievement, and it has had long-lasting benefits. As Terry Brown argues, “Unlike Papua New Guinea, the Solomons are still largely gun free.”

Beyond this uncontested contribution, however, the nature of RAMSI’s score-card is a matter of intense debate.

Nicholas Coppel documents RAMSI’s claimed achievements. According to him, RAMSI has strengthened institutions, delivered “key outcomes” in the area of law and justice, and helped the economy, as well as public finances, recover.

Clive Moore adds that the People’s Survey, conducted annually from 2006 to 2013, has never shown support for RAMSI fall below 86%. This itself is strong evidence of an important contribution by the regional mission.

Terry Brown, on the other hand, has little positive to say about RAMSI beyond its extraction of guns. It neglected health, education and infrastructure (building prisons but not hospitals), and supported too many, too highly paid advisers.

Ashley Wickham criticizes RAMSI for not doing enough to influence SI political culture, and for missing opportunities for influence by working too separately.

Other authors take the middle ground. Benjamin Malao Afuga acknowledges the achievements that Coppell articulates, but balances them by noting areas of failure, including the failure to capture, or to keep in custody, key combatants from the pre-RAMSI civil disturbances.

Other authors are more agnostic. Graham Baines argues that it is “too early to reach substantive conclusions” about the impact of RAMSI. Clive Moore agrees that it is “a difficult task.”

Several contributors caution against criticizing RAMSI on the basis of unrealistic expectations. Vella says that RAMSI “has not, indeed could not, build peace and reconciliation.” Afuga notes that “the immediate future of the country lies in the hands of Solomon Islanders.” Baines argues that it is unrealistic to expect RAMSI to influence SI political culture, as Wickham criticizes it for failing to do.

Several authors also credit RAMSI for providing Solomons with breathing space: “some needed space”, in the words of Baines, or “a little extra space”, in the words of Wood. Wood argues that RAMSI is a case study of how little influence donors in fact have, noting its limited impact on governance despite its massive relative size. But, Wood goes on to say, while deep change can only come from within, aid can work, and presumably has in Solomon Islands, to “hold things together.” This is about more than getting guns off the street. “Holding crucial institutions together” and preventing their further decay has also been important. (Wood lists the Electoral Commission, the police force and the Finance Ministry as areas where RAMSI has had a positive impact.)

3. What could and should RAMSI have done differently?

From this collection come a number of suggestions for things RAMSI should have done differently.

Ashley Wickham argues that much more use should have been made of in-line advisoes. The successful governance interventions, Wickham argues, were in-line ones, such as in the Auditor General’s Office and the Internal Revenue Service. More use of such positions “could have broken the cycle of ineptitude and corruption that sadly still exists in the public service today.” As Wickham notes, this is not new advice, and nor is it advice that has only been given in relation to Solomon Islands. Wickham also argues that funds should have been used to educate SI children overseas in order to give “the next two or three generations of high achievers a solid metropolitan education experience.” Wickham’s proposal is:

for Australia and NZ to revise their education policies and each year take all SI’s year 5 and year 6 students achieving B+ passes to study in Australia and New Zealand to complete their high schooling and prepare for tertiary studies.

Terry Brown agrees with Wickham that RAMSI’s advisers were often ineffectual. He adds that they were very expensive, arguing that RAMSI advisers were sometimes paid 13 times their local counterparts:

They were certainly not doing 13 times the amount of work; locals often resented this high pay, and felt that many RAMSI advisers were building up large savings back in Australia while they suffered to survive.

Baine argues that mistakes were made in the in early days: advisers and the “over-built and maintenance-costly” Auki prison.

Clive Moore argues that RAMSI and its police intervention, the PPF or Participating Police Force, must take “a great deal of the responsibility” for the 2006 Honiara riots since the riots occurred “when the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force was weak and the PPF was largely in control.” (p.30)

The PPF’s way of dealing with social tension was very Australian, and they lost control of the situation. I don’t think they had any idea of the capabilities of a Solomons mob moving fast.

Both Clive Moore and Terry Brown argue that RAMSI’s military presence went on far too long. According to the latter, a military presence hasn’t been required in the Solomons “for many years.”

Conclusion

Of course, answers to these three questions are related. The more positive you are about Solomon Islands, the more positive you will be about RAMSI. The more positive you are about RAMSI, the less you will see the need for things to have been done differently.

Nevertheless, it is still useful, we would argue, to separate out responses under these questions or headings. In particular, it makes it clear that even if one is not totally optimistic about SI, one might still be mainly positive about RAMSI. Similarly, even if one is mainly positive about RAMSI, one can still think that it could have done at least some things differently.

Although RAMSI is now winding down, the lessons learnt from the intervention are still of enormous relevance, for at least two reasons.

First, RAMSI may be wound back but the huge concentration of aid in Solomon Islands will remain. Indeed, there seems to us to be more continuity than change in the attitude of RAMSI’s backers towards their charge. The end of the military presence is of little consequence to the Solomons if those who argue that none has been required for several years are correct. And the management of non-policing aid by bilateral donors directly rather than through RAMSI also appears to be a second-order change. If the Solomons ship is taking in water, then the aid journey will become more, rather than less, difficult.

Second, RAMSI has global lessons. It is a textbook case of both the utility and the limits of large aid-backed interventions. On the one hand, such interventions can be critical for ending violence, restoring stability and expanding services. On the other, they do not put countries on the road to prosperity. Rather, they buy them time to work out their destiny. The history of aid suggests that many countries make good use of this time, and in the end make the right decisions: think of much of Africa and of Korea [pdf]. But by no means all do.

We commend this collection [pdf] to all who are interested in the future of Solomon Islands, and to all who are interested in the use of aid in fragile states.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre. Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Democratic Institutions at the Australian National University.

Clarification: An earlier version of this post included a comment calling for RAMSI surveys to be released. The People’s Survey results are publicly available–the authors were referring to the underlying data.

Leave a Comment