We’ve made our submission [pdf] to the Senate inquiry into Australia’s overseas aid program and on Friday we’ll join others in Sydney in answering the committee’s questions. At more than 40 pages, our submission is lengthy, despite our best efforts not to duplicate much of the material already published on this blog by ourselves and others over the past six months. Perhaps some few of you will read the whole thing. For those who do, you’ll find some points we haven’t made before (as well as a few we have) and fourteen specific recommendations.

For those who can’t come at 40 pages, this post pulls out our main points, boiled down to the following half-dozen propositions. Our overall message? That the aid program is going through a tough time right now, but should pull through if the government can achieve a certain kind of policy, budget and management stability.

1. The current budget situation is a joint product, and it’s not disastrous

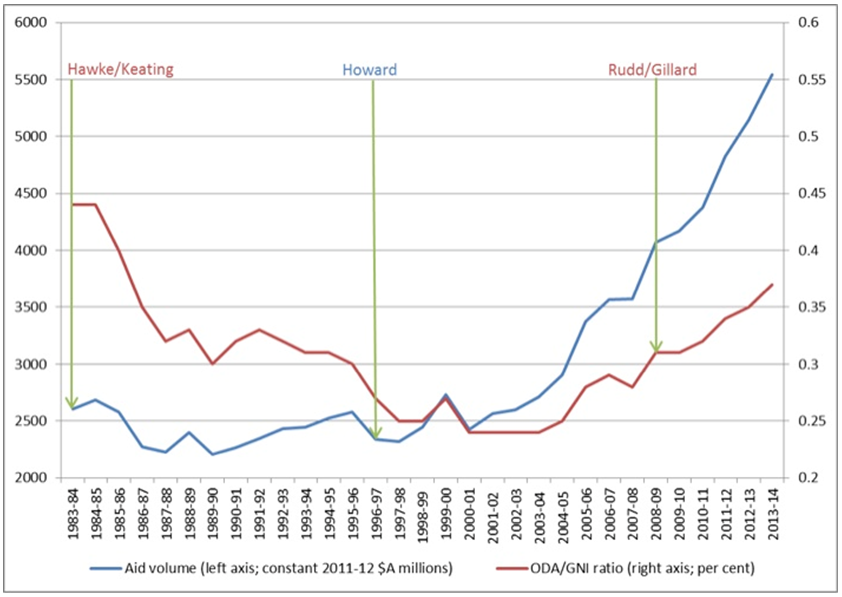

The inquiry’s terms of reference rather imply that Australia’s aid program was blown out of the sky by a deficit-busting missile on or about the date of the 2013 election. In fact, the bipartisan commitment to reaching an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.5 per cent by 2015-16 was replaced, in May 2012, by a new, unstated bipartisan commitment to hollow out the forward estimates for aid.

Labor did so in May 2012, May 2013 and August 2013, to the tune of $5.7 billion, and also made reallocations within the aid budget totalling $750 million in December 2012 and May 2013 for onshore asylum-seeker costs. Australia’s Security Council campaign slogan, ‘we do what we say’, was by this time looking tatty. Then, in September 2013, the incoming Coalition government took all that was left in the forward estimates and another $650 million or so from the current year’s allocation. Thus the bottom line we now have, just over $5 billion, is the product of some nice teamwork.

We don’t suggest, however, that this bottom line is an embarrassment. With a program of this magnitude, Australia is still providing aid at a level commensurate with its global economic standing. Of course more could and should be achieved with more aid (see our third point below). But the program still contains within it considerable scope to maintain Australia’s major bilateral and multilateral partnerships at credible levels and accommodate new priorities within a year or two, or faster if resources are reallocated within the DFAT portfolio or between portfolios.

2. Making three big changes simultaneously might well prove to have been disastrous

Abruptly reducing aid, integrating AusAID into DFAT and substantially reducing the number of former AusAID personnel are three major and logically independent steps, which have been taken at the same time. A lesser or more quickly implemented budget cut in 2013-14, and/or a staged or less obsessive integration of AusAID into DFAT, and/or a staged or more targeted approach to achieving staffing reductions, might have reduced the scope for things to go badly awry.

As it is, there will likely be diplomatic friction over certain program cuts (most of which are still invisible), a dangerous period of senior management inattention to the fundamentals of aid planning and management, and a deleterious loss of expert capacity. Time will heal, of course, but the self-inflicted wounds needn’t have been so deep.

Now we come to our more constructive propositions.

3. Budget predictability strengthens aid effectiveness

The foreign minister, Julie Bishop, has issued a rather ironclad guarantee of budget predictability, with aid to stabilise at its present level in real dollar terms. Provided the iron cladding can in fact withstand marauding fiscal consolidators, this has much to recommend it, even by comparison with rapid growth. Predictability is essential for long-term planning. And stability promotes a methodical, orderly approach to program development and constrains the ability of governments to generate ‘announceables’, great and small, on the fly. It introduces a greater degree of competition into the resource allocation process. It increases the amount of time and effort that can be applied to managing the aid program of today as opposed to planning for the aid program of tomorrow.

We argue, however, that in order to keep faith with its continued (but not currently time-bound) commitment to the 0.5 per cent ODA/GNI target, the government should stabilise aid volume not by reference to a real dollar figure but by reference to the post-cut ODA/GNI ratio, which is 0.33 per cent. Holding the ratio constant at this level would require volume growth of perhaps $300 million per year rather than the $100 million per year required to hold the real dollar figure constant. Targeting the ratio in this way would not move us toward the 0.5 per cent target but at least we would be treading water, and not becoming less generous. And $300 million per year is less than it seems when allocated across all major bilateral and multilateral purposes.

4. A policy framework and a linked medium-term expenditure framework for the aid program should be released with the 2013-14 budget

We don’t doubt the government will get around to releasing a policy framework for the aid program, probably with the 2013-14 budget. One is required, but it should not be rushed. Careful consideration of what is needed and feasible at the level of our major bilateral programs is much more important. Our main concern is to highlight areas in which the policy framework should deliver a clarity that is currently lacking. There are many such but we give particular attention to three.

The first is the place of commercial considerations in the aid program. Commercial considerations, at one level, have a legitimate place. However, it is impossible to know right now whether the government is contemplating the re-tying of aid procurement or the use of aid to subsidise Australian firms wishing to enter or expand within developing country markets. Most of what has been said about using aid to ‘leverage’ private sector engagement in development is deeply ambiguous. The policy statement must disambiguate, preferably by ruling out re-tying.

The second is the use of aid for action on climate change in developing countries. The government’s position on this cannot stand. Some aid funding must in the end be used for some purposes related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. The sooner this is factored into budget planning, the better.

The third is the use of aid for the community detention of asylum seekers, onshore in Australia and potentially also offshore. The government strongly opposed using aid for onshore asylum seeker costs when in opposition but has not touched the funding appropriated to the immigration portfolio for this purpose. Spending in this category should diminish as onshore processing becomes a distant memory. The government should resist any temptation to use aid for community detention offshore.

Once the above and a slew of other policy uncertainties (some of which we also discuss) are cleared up, it will be important to link the new aid policy framework to resource allocation—in other words, to develop it into a medium-term expenditure framework. That’s precisely what the 2012 Comprehensive Aid Policy Framework (CAPF) was meant to be, even though it ceased to be relevant within six months of its publication owing to budget raids. The Coalition supported the concept of the CAPF when it was recommended by the Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness. We therefore assume they will want to use a vehicle of this kind to link policy to funding.

5. Stabilising aid management is no less a priority than stabilising the budget

We think the integration of AusAID into DFAT will bring efficiencies and other benefits, though we didn’t think it needed to involve erasing an identifiable, professional aid organisation within DFAT. The latter point is now academic and, in the long run, we don’t think it matters too much where aid policy and management sits. All sorts of approaches can be found among OECD donors and Australia’s new arrangements are common and generally effective. The priority at this point should be to ensure that these new arrangements come together in the best possible way.

We could do worse than look to Canada for guidance. The corresponding merger there has many critics but, to our eyes, some aspects of it have been intelligently done. For one thing, aid policy and management functions, while distributed across the foreign ministry, fall under the overall responsibility of a Secretary-level official (with two others covering foreign policy and trade). A second point is that several senior officials of the former aid agency have been placed in positions with very substantial foreign policy responsibilities. And a third point is that the merger is being implemented under the guidance of an external advisory body, as seems appropriate for a complex and risky undertaking of this nature.

We think similar moves would be beneficial here. We’d also like to see ‘development’ figure prominently in the title and mission statement of the integrated department, as in Canada. Both sides of the shop must change. And we strongly recommend that once the staffing reductions are done, a thorough skills stocktake and workforce planning exercise be undertaken. There will be big gaps to plug.

6. Don’t reinvent wheels in pursuing performance-based resource allocation

Finally, we can understand the oft-expressed disquiet of the foreign minister about the way in which the previous government interpreted recommendation 39 of the Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness, which called for a series of ‘hurdles’ to be identified so that the growth of the aid program wouldn’t get out of step with its performance. The former government responded with the CAPF’s results framework, which sets out mostly ‘headline’ policy-related targets and a few process targets. The first and so far only Annual Review of Aid Effectiveness found absolutely nothing amiss with respect to these targets and generally failed to provide a clear and frank view of the strengths and weaknesses of the aid program, in aggregate and at country and partnership level. Disquiet was inevitable.

However, we hope that the government’s quest for a new set of performance ‘benchmarks’ (they’ve stopped saying ‘hurdles’) for the aid program doesn’t reinvent too many wheels. For one thing, the government shouldn’t set benchmarks that are beyond its control, such as general governance benchmarks for partner governments. It shouldn’t fall into the same trap as the previous government and make too many benchmarks policy-related (‘we will spend X per cent of our aid on Y’). We expect the government will wish to establish more benchmarks relating to operational and organisational effectiveness, which in our view would be appropriate. If so, our recommendation is to look at the range of quite robust systems already in place in the aid program—of which we identify seven—and essentially establish broad benchmarks that measure the extent to which each of these systems is kept in order and consistently applied.

If a simple, high-level set of benchmarks can be devised, this will greatly assist in both the management of aid and the communication of its achievements. A good results framework for the aid program would provide a strong basis for a CAPF-style expenditure framework, for annual reporting against same and for other internal and external reviews. In addition, endorsement by the government of the pre-existing Transparency Charter, as well as the regular conduct of stakeholder surveys (like ours), would do much to improve not only public accountability but also program performance as measured against whatever benchmarks are adopted. Public and parliamentary scrutiny and stakeholder or ‘customer’ feedback are powerful spurs to the achievement of aid effectiveness.

Those, in very brief form, are our main points. The budget and integration decisions have been taken and any unfortunate consequences are now sunk costs—and for the most part short-term ones. It’s time to look ahead and think about how a $5 billion aid program under integrated and leaner management can work most effectively to achieve its newly articulated but ultimately quite familiar purpose: ‘to promote Australia’s national interests by contributing to international economic growth and poverty reduction’.

Robin Davies is Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre. Stephen Howes is Director of the Centre.

Leave a Comment