(Editor’s note: this is a guest post by Professor Biman Chand Prasad from the University of South Pacific.)

Battered by coups, sluggish growth and in recent years the global increase in food, fuel and commodity prices, Fiji economy is struggling to regain its feet. The December 2006 coup led by Commodore Frank Bainimarama was the fourth in the last two decades. Bainimarama, in ousting the Laisenia Qarase-led Government promised to tackle corruption, put an end to racially discriminatory policies and reform the race-based electoral system.

The Prime Minister promised a general election under a new Constitution in 2014. However, analysis of previous coups in Fiji and the economic recovery plans followed by governments provides little optimism for a swift economic recovery soon.

Apart from the initial shock of the coup, the spike in food and fuel prices in 2008 and the global economic crisis in 2009 put Fiji firmly on the back-foot and made the much-sought after economic recovery even tougher. Government’s hardline approach in dealing with the media and its other critics has not inspired confidence amongst investors and the public. It seems that what began with the best of intentions—changing the political and economic landscape of Fiji for the benefit of the ordinary people—will be harder to achieve than expected.

GDP Growth

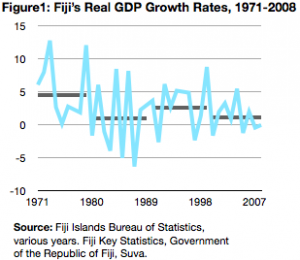

Fiji’s growth rate in the first decade of independence was volatile but on average better than what has been experienced since the 1987 coups. Fiji’s real GDP growth rates for the period 1971-2008 are shown in Figure 1.

Fiji’s growth rate in the first decade of independence was volatile but on average better than what has been experienced since the 1987 coups. Fiji’s real GDP growth rates for the period 1971-2008 are shown in Figure 1.

The government’s estimates show that in 2009 economic output declined by about 2.5 per cent (Ministry of Finance, November, 2009). This is a significant decline and goes against the initial forecast by the government of positive growth of 1.9 per cent. The decline was largely due to the floods at the beginning of 2009 and the domestic impacts of the global economic crisis. All sectors of the economy appear to have declined in 2009. The contraction was led by the transport, storage and communication, wholesale and retail trade, agriculture and forestry, manufacturing, public administration and defence, education, health and social work, and hotels and restaurants. Sectors that grew modestly included construction, mining and quarrying, financial mediation, fishing, real estate and business, electricity and water, and other community, social and personal services.

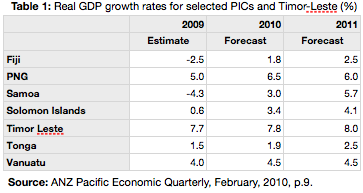

The picture for the next two years does not look optimistic for Fiji. It is expected to do poorly in comparison to other Pacific Island states (see Table 1). The growth forecasts for Fiji for 2010 and 2011 are lower than for almost all other Pacific Island countries.

The picture for the next two years does not look optimistic for Fiji. It is expected to do poorly in comparison to other Pacific Island states (see Table 1). The growth forecasts for Fiji for 2010 and 2011 are lower than for almost all other Pacific Island countries.

Investment

Investment, the key to Fiji’s economic recovery, has been low since the 1980s. In their development plans, various governments set investment targets of 25 per cent of GDP. None of them came anywhere close to this target. A review of investment prior to the coups of 1987 shows that it was relatively high during that time, ranging from 15 per cent to more than 25 per cent of GDP.

Investment levels have been directly affected by political uncertainty and inconsistent policies by subsequent governments. Financial incentives failed to attract the high levels of foreign investment anticipated. The present government continues to provide tax and financial incentives but there are not enough takers.

Inflation, Exchange Rates, and Foreign Reserves

While inflation was relatively low in 2005 and 2006, it increased in 2007 and 2008 due to the sharp increases in oil prices and in food prices, largely rice and wheat prices. In the second quarter of 2009, the inflation rate was down to 2.3 per cent; but by the third quarter it had risen to 6.3 per cent, most likely as a result of the devaluation of the Fiji dollar by 20 per cent in April. Fiji is likely to end up with a higher level of inflation in 2010 as a result of the devaluation.

Fiscal Policy Responses

While the government has put out an optimistic macroeconomic target for the medium term, its policy interventions and the uncertain overall economic and political environment suggest that the targets are unlikely to be achieved. Closely linked to the revenue and deficit policies is debt policy. As a percentage of GDP, total government debt declined by 3.4 per cent in 2007. However, it increased in 2008 and 2009 by 0.8 and 1.2, respectively.

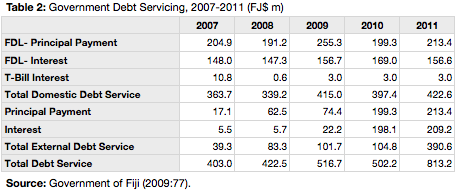

Debt figures show that from 2011 the situation will be very tight and this could have implications for future macro-economic stability. Table 2 shows the total debt servicing requirements of the government between 2006 and 2011.

Debt figures show that from 2011 the situation will be very tight and this could have implications for future macro-economic stability. Table 2 shows the total debt servicing requirements of the government between 2006 and 2011.

The global bonds issued in 2006 account for around 56 per cent of total external debt. These bonds carry an annual fixed rate of interest of 6.875 per cent. They will mature in 2011 and will require a bullet payment of more than US$150 million, amounting to roughly FJ$300 million. This repayment is likely to put a serious strain on government’s ability to service debt and run an appropriate expenditure policy. It could create a foreign reserves crisis, nullifying the gains made through the 20 per cent devaluation. This would be followed by a money supply contraction, a rise in domestic interest rates and, in effect, reduced domestic lending. A further devaluation of the dollar cannot be ruled out if the economy does not make a turn-around very quickly.

Since the 2006 coup the Reserve Bank of Fiji (RBF) has run a tight monetary policy. This is partly in response to the impact of the global economic crisis, which continues to have a serious impact on exports, remittances, and tourism. The decline in these key areas has put further pressure on foreign reserves.

Future outlook

The tourism industry has been the leading industry in Fiji for the past 20 years. While vulnerable to coups and natural disasters, it has been quick to recover from both. Recovery after the 2006 coup has been slow, partly because of the impact of the global economic crisis and partly because of the political instability (figure 3). The importance of tourism industry to Fiji cannot be overstated. It now contributes about 18 per cent to GDP and provides employment directly and indirectly to about 40,000 people. In both 2009 and 2010, Government gave the Fiji Visitors Bureau $F23.5 million for marketing and promotion.

Tourism will be the key industry for Fiji’s future economic growth even though infrastructure for expansion and overpricing will need to be addressed to facilitate growth.

The current government has been in power for the past three years and it says it will stay in power until there is a general election in Fiji 2014. There is now almost zero opposition to the government from any section of the community in Fiji. The international development partners are to a large extent doing business as usual and there is a thawing of relationships with Australia and New Zealand. China and India have continued to do business as usual with Fiji. China, in particular, has taken more interest in Fiji in terms of its support for infrastructure building.

The current government has been in power for the past three years and it says it will stay in power until there is a general election in Fiji 2014. There is now almost zero opposition to the government from any section of the community in Fiji. The international development partners are to a large extent doing business as usual and there is a thawing of relationships with Australia and New Zealand. China and India have continued to do business as usual with Fiji. China, in particular, has taken more interest in Fiji in terms of its support for infrastructure building.

Under the present circumstances the government should consider removing the state of emergency, lifting media censorship and initiating inclusive political dialogue for the development of a new Constitution so that elections could be held even before 2014.

The Bainimarama Government has a wonderful opportunity to engage in a unification process that could help achieve the vision of ‘A Better Fiji for All’. The Prime Minister has said on numerous occasions that he wishes to eliminate the politics of race. This goal cannot be achieved without engaging the broader society in open dialogue on critical issues, including achieving consensus on a new constitution and creating opportunities and conditions for uniting the people.

The Bainimarama Government could leave a lasting beneficial legacy if it takes a different approach over the next year—that of unifying the country in the common vision of ‘Making a Better Fiji for All’. It is time Fiji takes on the lessons from its past.

Professor Biman Chand Prasad is the Dean of Faculty of Business and Economics & Chair of Oceania Development Network, Faculty of Business and Economics, The University of the South Pacific, Fiji.

This article was first presented here as an economic survey in the Pacific Economic Bulletin Vol 25 No 2, 2010. Crawford School of Economics and Government, ANU

Can you explain the sudden decrease in tourism arrivals in 2013?

why do you have a picture of the virgin islands on an article about fiji? you call yourself a reliable source ?