Covers of the World Bank Health Financial System Assessments

Making health dollars go further in the Pacific

By Maude Ruest

28 June 2018

As population grows and as the prevalence of chronic and complex diseases increases, the cost of delivering health services in the Pacific is on the rise. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have become the biggest contributor to the burden of disease, while the unfinished agenda of reproductive, maternal and child health, malaria, tuberculosis and HIV continues to significantly affect some countries. In all Pacific countries, deaths from NCDs outnumber deaths from communicable diseases.

Like the rest of the world, the Pacific Islands are faced with the constant challenge of covering their population’s growing health needs with limited financial resources. Furthermore, as income levels increase and countries ‘graduate’ from external development partners (DP) funding, external resources to the sector are not expected to increase on par with costs. This further pressures national health systems to find ways to spend their health dollars more efficiently, and countries will have to develop strategies to manage the financial and institutional changes resulting from these transitions in a sustainable manner.

The World Bank recently conducted Health Financial System Assessments (HFSAs)[1] in Papua New Guinea (PNG), Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Kiribati. These reports aim to evaluate critical opportunities and constraints faced by countries and identify ways to maintain or further improve health outcomes as the health sector goes through changes in its financial and institutional environment.

Total health expenditure per capita for most Pacific Islands is in the range of what can be expected given their levels of income. However, based on available data when the HFSAs were written, in the decade to 2014[2] real total expenditure per capita declined or stagnated in PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Kiribati, largely because nominal increases in expenditure have been offset by population growth.

Figure 1: Nominal and real total health expenditure per capita (in local currency), 2004-2014

Source: World Development Indicators 2017, World Bank

Health expenditures are largely public (81% of total health expenditure in PNG and Kiribati, 90% in Vanuatu and 92% in Solomon Islands in 2014), with varying but relatively high reliance on external financing (Solomon Islands and Vanuatu were in the top ten countries globally with the highest share of total health expenditure financed externally in 2014; in PNG and Kiribati, DPs provided one in every five dollars spent in the health sector that same year). Ongoing high levels of external financing, compounded with low out-of-pocket (OOPs) payments, create a unique health financing landscape in the Pacific. Pacific countries are not experiencing the more traditional health financing transition characterised by a shift from low spending on health and high OOP to higher spending on health and lower OOP.

Following a decade of substantial (but volatile across years) external financing to the health sector, DP support has started decreasing, but is expected to remain significant. Due to increasing income levels, Kiribati stopped receiving Gavi support for immunisation in 2017, whereas PNG and Solomon Islands entered their five-year[3] accelerated transitions in 2016 and 2017 respectively. Vanuatu is not eligible for Gavi support. Although Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (GF) support is provided to the four countries, all have seen reductions in grant allocations since 2014.

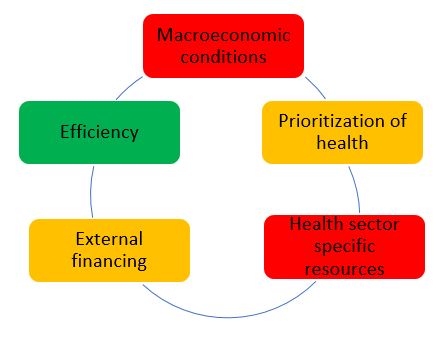

In this context, governments will have to explore alternative sources of funding to meet the sector’s needs (Figure 2). Increased financing opportunities are limited in PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Kiribati. Economic growth forecasts are modest, and health already represents a relatively large share of national government expenditure (between 10% in PNG to 15% in Kiribati). Social health insurance, voluntary private insurance and community-based health insurance are not feasible options to mobilise additional resources given the small populations and/or large informal sectors in the Pacific islands. Low reliance on OOPs should be maintained to ensure pooling of risk and equitable access to healthcare (noting that OOPs don’t include indirect costs such as travel, which can be significant in remote outer islands, or that low OOPs can be a sign of inequitable and low access and utilisation of services, as witnessed in PNG). Finding ways to improve the quality of expenditure, particularly through efficiency gains, offers the most immediate option for freeing up additional money for health in the short term.

Figure 2 – Components of fiscal space for health (red- unlikely, orange-limited scope, green-most likely)

The HFSAs identified a range of priority actions, mostly within the health sector control, that could be implemented to achieve immediate and ongoing substantial improvements in health service delivery.

Strengthening governance and accountability arrangements at all levels of the health sector is a clear prerequisite to improving efficiency, quality and equity of service delivery. This includes, but is not restricted to, committing to regular and thorough performance monitoring and evaluation. To do that, ministries of health and DPs must improve access, use and dissemination of timely and quality data. DPs need to uphold their commitment to the development effectiveness agenda to align and coordinate their support, funding cycles and financial systems to national ones to help reduce fragmentation and strengthen national systems. Improving national financial management systems and cash management would facilitate DPs increasing on-system support. Finalising and implementing clear demarcation of roles, responsibilities and reporting lines through all levels of facilities, and appropriately resourcing them, will help deliver quality services and improved accountability.

Increasing efficiency of health spending will help ensure finite resources are used to purchase the best quality and value goods and services. The WHO estimates that 20-40% of all health resources are wasted globally. Focus for improved efficiency includes, but is not limited to (i) targeting high return health interventions such as prevention and primary health care, focusing on frontline service delivery and the most at-risk populations; and (ii) better purchasing and management of inputs, including through improved planning and budgeting, for better expenditure outcomes in larger expenditure areas such as health workforce remuneration and staff benefits, medicines and vaccines, and hospitals.

PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Kiribati, like other Pacific Islands, face difficult geographic, environmental and social determinants of health. Improving health outcomes requires increased partnership and collaboration within the health sector and across sectors. Within the health sector, this includes better integration of major disease programs, often largely DP funded, into the broader health system. This is particularly urgent considering the transitions from some DP support. Furthermore, as it is unlikely that governments will be able to maintain DP levels of financing for key disease programs, a more effective approach to integrated service delivery needs to be implemented. This also includes partnering with non-state actors, like faith-based organisations, some of which are already providing significant support (in PNG church health services deliver 50% of health care). In other sectors, this includes building relationships with central agencies that manage budget, staffing and payroll, as well as building meaningful engagements with other ministries in charge of education, housing, and access to water.

Taking these actions, with assistance where required, will make health dollars go further, but also help countries to make a case internally, as well as with DPs, for the additional funds that will inevitably be needed to manage the increasing demands on the health system.

This blog post is based on a paper ‘Spending better for health in the Pacific – a study of PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Kiribati’ to be presented at the 2018 Pacific Update in Fiji on 5-6 July.

Notes:

[1] With support from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT), the World Bank has been providing a small program of health advisory services and analytics in the Pacific region since 2012 to assist countries and development partners improve health service outcomes through more efficient, equitable and quality expenditure. More recently, additional targeted DFAT funding under a Multi-Donor Trust Fund was provided to assist countries in East Asia and the Pacific prepare for reductions in external funding of health programs. The HFSAs were conducted as part of this work.

[2] 2014 data was the latest year available in the World Development Indicator database when the HFSAs were completed in 2017. The database now includes 2015 information, but the indicators are different as they have been updated to reflect the new system of health accounts (SHA 2011) reported in WHO’s Global Health Expenditure Database. More time will be needed to update the analysis with the revised 2015 Indicators.

[3] A recent Gavi board decision extended support for one additional year, meaning PNG and Solomons will receive Gavi support until the end of 2021 and 2022 respectively (rather than the end of 2020 and 2021).

About the author/s

Maude Ruest

Maude Ruest is a Health Economist with the World Bank Pacific Health Team.