The PACER Plus negotiations drag on, seemingly without end. There are no potential trade gains for the Pacific from this free trade agreement. They already have tariff-free access to Australia and New Zealand. And they have little to export in any case. Lowering their own tariffs is not going to lead to a burst of growth, and it is doubtful that an investment chapter will result in increased levels of foreign investment.

The PACER Plus negotiations involve not only trade and investment, but also aid and labour mobility. There won’t be any more aid to the Pacific because of PACER Plus, just perhaps more “aid-for-trade”, i.e. aid for trade-related ends. That leaves labour mobility, an area where the Pacific could gain significantly, and that has repeatedly been identified by the Forum Island Countries (FICs) as the most important issue under PACER Plus for them.

My understanding is that the FICS have three demands with regards to labour mobility. One is that the existing seasonal worker arrangements, Australia’s Seasonal Worker Program (SWP) and New Zealand’s Recognized Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme, be given legal underpinnings by including them in the trade agreement. The second is that the caps on these schemes should be lifted or removed. The third is that the schemes should be extended to additional sectors.

All of these demands are problematic. The first has been rejected on the grounds that it would be open to a WTO challenge, and set a precedent for Australia and New Zealand for other free-trade agreements with Asian countries.

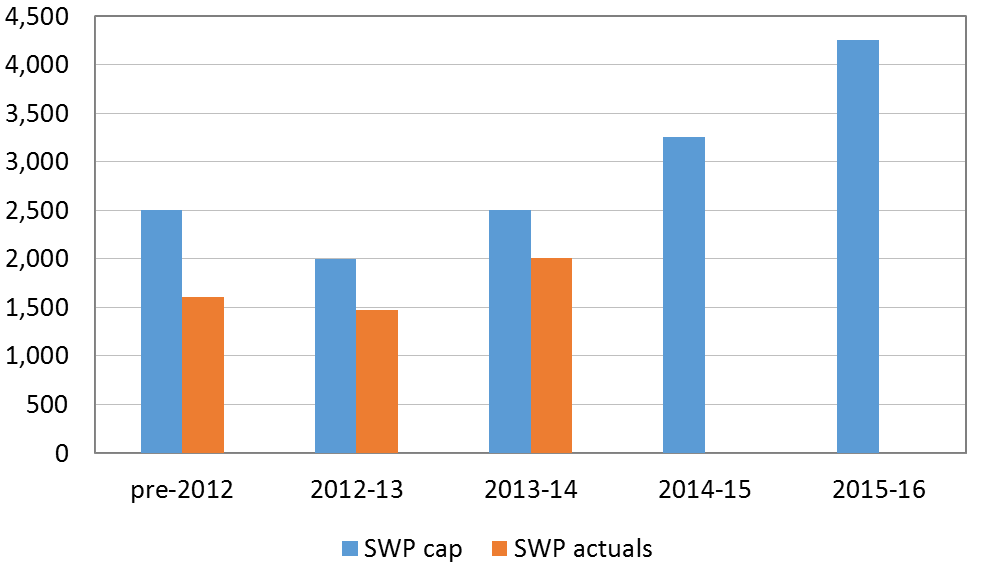

On the issue of caps, New Zealand has already announced an increase in its cap for its RSE from 8,000 to 9,000. That is meaningful, because the New Zealand cap is binding. Increasing the cap by another one thousand means that another one thousand (mainly Pacific) workers will come to New Zealand. Australia has been asked to increase its cap as well, but the problem here is that the cap is not binding. Lift the cap and not a single more worker might come. We have been well below the cap every year, and the cap, though low, is in any case increasing. In 2013-14, the cap was 2,500 and just 2,000 workers came.

Increasing Australia’s SWP cap won’t make any difference since it isn’t binding and is increasing anyway

Note: The pre-2012 cap covered several years

Note: The pre-2012 cap covered several years

Expanding the scheme to other sectors doesn’t make a lot of sense either. Australia tried that with extensions to sugar, cotton, aquaculture and seasonal tourism, but there have been very few takers. And for many other sectors, such as aged care, temporary workers don’t make a lot of sense.

In summary, the demands currently on the table miss the mark for a range of reasons. The good news is that Australia and New Zealand seem to have accepted that they will have to discuss labour mobility and make concessions if they are to get a PACER Plus agreement. So a side agreement might be possible, but not a treaty-backed labour mobility scheme. Would could such an agreement look like?

The key issue for Australia’s SWP is the reform of its Holiday Worker Program. Under this scheme, backpackers are currently rewarded for three months work on a farm by a second year’s visa. This provision was introduced by the Howard government to solve the horticultural labour shortage in 2006, at a time when it was unwilling to introduce a seasonal worker program. It has been incredibly effective in channelling an ever-growing number of backpackers onto farms.

Pacific seasonal workers simply can’t compete with backpackers. The number of backpackers who applied for a second-year visa on the basis of farm work in 2005-06 roughly equals the number of Pacific SWP workers last year. But in the meantime the number of backpackers on farms has shot up to over 40,000! No wonder the SWP is languishing.

Pacific seasonal workers can’t compete with backpackers

Note: The “backpackers on farms” numbers are estimates based on 90% of those who received a second Working Holiday Visa. The actual number is probably many more, as not all who work on a farm would apply for the second year’s visa.

Note: The “backpackers on farms” numbers are estimates based on 90% of those who received a second Working Holiday Visa. The actual number is probably many more, as not all who work on a farm would apply for the second year’s visa.

Now that Australia has the SWP, there is no longer any justification for this second year provision in the backpacker visa. If Australia wants to encourage backpackers to work (though the visa category is promoted as one not primarily intended for work), it should allow those who take any job for three months to get a second year visa, not require that they work on a farm (or mining or regional construction site, though very few do). If Australia is serious about the SWP, it will stop supporting another scheme that directly undermines it. Unskilled Pacific islanders can’t come to Australia as backpackers, a scheme reserved for rich countries. (New backpacker schemes are being developed with PNG and Fiji, but they will be highly regulated and capped at very low levels.) Backpackers can work in every sector of the economy. Why push them into the one sector which is able to employ unskilled Islanders: horticulture?

There are a lot of other things Australia could do to increase the numbers under the SWP. (Pre-election, the Coalition promised a review of the program with an eye to expanding it. More than a year on, that hasn’t happened.) They key is to build employer demand. We could cut red tape, make the scheme more flexible and economical to employers and crack down on illegal labour. But the two most important things we could do are reform the backpacker scheme and increase the SWP cap. Both together are important. Increasing the cap on its own will achieve nothing. Reforming the backpacker scheme and not increasing the cap will quickly make the SWP cap binding.

The Pacific doesn’t count for much in Australia, but Australia wants PACER Plus, and the Pacific needs more labour mobility. Fixing the SWP would not be at the expense of Australian jobs, but those of OECD backpackers. That would be good for the Pacific and good for Australia. And it might even, finally, allow PACER Plus to be concluded.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Many thanks for this blog Stephen. Please see this link for a discussion I had with Amanda Vanstone regarding labour mobility and the PACER-Plus negotiations. It aired on Radio National’s ‘Counterpoint’ program earlier this week.

Regards,

Wesley