It has been five years since a post relating to religion and development appeared on Devpolicy. In those intervening years the word ‘religion’ only appears in six other posts, in each case it was included in the text for reasons other than in any way associated with development practice. For many Australian policy makers and practitioners this may seem a wise choice. Engaging with religion could risk legitimising a potentially divisive force or give standing to views that are contrary to what is needed for progress. What value could engaging with religion bring? In my book Religion and Post-Conflict Statebuilding I examine this question within the context of statebuilding.

To begin we should acknowledge the different religious contexts of most developing countries compared to those of many developed countries, such as Australia. By cross-tabulating the World Bank’s list of fragile and failed states to data available in the Gallup World View database (2006–2010), we find that on average 91% of people living within fragile states consider religion important to their daily lives compared to 50% in Australia (Nielson Poll 2009 [pdf]). It is not just failed states or those countries that tend to grab the extremist religious headlines that value religion, within our region Fiji was found to be the fourth most religious [pdf] society in the world.

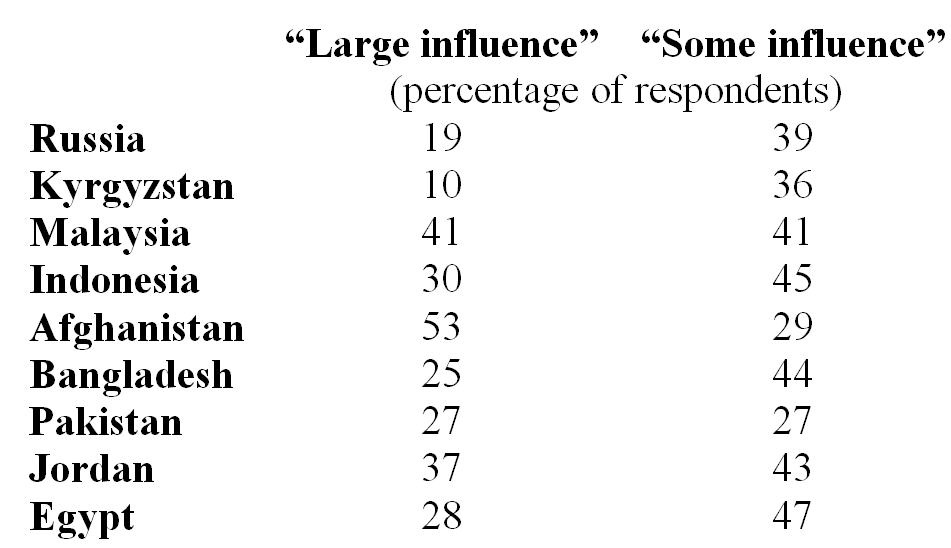

As those of us who have worked overseas know, it is in more than an individual’s spiritual growth that religion plays a role. Religious institutions themselves are actively involved in society, be it through the provision of services to legitimising authority and entrenching values that contribute to statehood and nationhood. One marker of the standing of religious institutions in society from which their influence spreads is the level of trust they hold. 80% of people in the World Bank’s list of fragile states have confidence in religious institutions compared with only 48% in their government. Another indicator is the view of what role religion should play in politics. A Pew Research Centre poll (Table 1) found large numbers of Muslim people from Europe through to Asia and the Middle East thought that religious leaders should have some influence, if not a large influence, in politics.

Table 1: Percentage of Muslims who say that religious leaders should have a small or a large political influence

Note: Countries selected by author.

Note: Countries selected by author.

Source: Pew Research Centre – Religion & Public Life.

This prominence of religion in politics has been considered within academia in the context of its divisiveness during conflict, as a spoiler during peace or as an inhibitor of development. There is limited research on the potential positive role of religion, and when it has been undertaken it is usually considered through a secular lens.

One of Australia’s leading experts on religion and development, Matthew Clarke of Deakin University, has written extensively on religion and development, noting the size of the Catholic Church’s humanitarian work or the extent of communal support instigated by faith-based groups. But even his work is largely presented through a secular lens. This can be problematic, as I have previously written about, because by doing so we project temporal humanist ambitions, such as the reduction of poverty or freedom, as ends in and of themselves when within religion they are only a means to, or sometimes dangerous diversions from, a spiritual end.

Understanding how religion can contribute to peacebuilding, statebuilding or development beyond a limited secular view requires reflecting on how decision making occurs within religious groups—in particular, how resources are allocated and towards which ends. Alternatively phrased: why would a religious group contribute its considerable resources, including high levels of legitimacy and trust, to what could be counterproductive to its cause, such as secular governance, plural nationhood or the adoption of certain rights?

To understand how such decisions are made we must begin outside the secular, rational world in which Western development and academia operates and instead engage with the cosmology of each religion through an understanding of their theology. To presume that every religion has a teleology (end goal) that aligns with a secular humanistic one is not only wrong but goes against some of the basic principles of development, namely respecting local ambitions and definitions of progress. Knowing the teleology of a religion suggests how resources will be allocated.

This becomes a challenge when some communities’ interpretations of their religious or cultural values do not align with those that Western donors are willing to support. Finding where the two overlap, those hopes and ambitions that ‘we’ agree upon is where religion can aid the Western development community. To do so requires moving beyond simplistic engagements of religion in which particular verses or sayings are selectively cut and pasted to match our world view, and instead moving towards recognising it as an alternative world view that may not align in all cases.

Denis Dragovic is the author of ‘Religion and Post-Conflict Statebuilding: Roman Catholic and Sunni Islamic Perspectives’ (Palgrave 2015) and holds a PhD in political theology from the University of St Andrews (UK). He has also worked for over a decade in conflict and post-conflict countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

Denis, I also look forward to reading your book. In 1997, with Bougainville slowly recovering from destruction and theft of property, I was involved in attempting to secure new two way radios for communities right across the region. Isolation, poor roads, lawlessness in some areas, challenged health and education services made the radios almost essential.

Australian Aid, so we were told by officials, was not possible because the radios were to be placed in community headquarters which were church run institutions or parish centres. It seemed that there was a fear that the support would be used for evangelical purposes or at least might appear to be a contribution by Australia to evangelical endeavour.

If there is a concern that the values of the religions, which provide communities with services, do not align with mainstream Western development values then there may need to be a review of Western development values. We have seen this throughout the history of PNG, officials or evangelists who see the need for local alignment with mainstream Western values as a prerequisite to receiving the cargo. There can be good reasons for this but when it is directed at a religion and not state it would seem unfair. If this principle were applied to secular institutions development workers would need to face the probability that they are providing support to institutions and officials showing very little practical signs of alignment with mainstream Western practice.

Lawrence Stephens

Hi,

The points you raise are critical to the development endeavour and much broader than my specific contribution in this book. You ask, what do we do when religious/cultural values don’t align with those of mainstream Western development. Well, for those who believe in grassroots development the answer should be that we don’t impose our values on others, but of course communities are not homogenous units but complex constellations of individuals some who may welcome Western development and others who don’t. This leads into the much more complex debate of whether all aid is a universal right or only humanitarian aid being universal and development assistance being an extension of Western values, the former being apolitical the latter highly political. Rather than arguing a particular perspective, my book offers a model that offers insights into the extent of the assistance that religious groups could offer in the statebuilding endeavour and then providing insights into how to better understand the relevant doctrines of two religions in relation to post-conflict statebuilding, but I leave it to individuals to interpret for their particular situation whether this is to be used as a tool to avoid potential challenges from religious groups or as a means of better tailoring assistance to believer’s hopes and aspirations.

As for religion and culture, yes I agree that religion is a factor that shapes the broader concept of culture, but its a particularly important one that seems to be wilfully taken off of our radar. Its as if there is an unwritten rule that allows for discussions of tribal structures, traditions and practices but none that may fall under the rubric of religion and in particular if its one of the major religions.

Thanks for your comment. Please note that the first chapter of my book is available for free from the Palgrave site.

Denis, thanks so much for this post — I agree that religion is a hugely underrepresented topic in development, and I look forward to reading your book.

Certainly it would be fantastic if development agencies and practitioners routinely sought a deeper understanding of the religious contexts in which they work, with the goal of identifying those mutual ‘hopes and ambitions’ you mention. But I wonder if I could press you a little bit more on ‘what now?’, in those cases where religious/cultural values don’t align with those of mainstream Western development. Do we (development agencies/workers) just have to walk away? I’m thinking particularly of issues of power and oppression within religious communities, and the risk that we might overlook these by accepting the most dominant interpretation of values.

More generally: should (or indeed can) we consider ‘religious’ and ‘cultural’ values as separable? Personally I am inclined to think of religious belief/practice as inextricable from culture, and vice versa. Should those working in development approach ‘religion’ differently from ‘culture’?