International official development organisations – entities such as the World Bank and the Global Fund – raise funds every few years through replenishment rounds. These involve major conferences at which donor countries are pressured to give more than last time and more than comparator countries. Different organisations operate on different funding cycles, so the extent to which these replenishment rounds coincide varies over time. And it just so happens that four replenishment rounds are occurring between now and the middle of next year.

The four upcoming replenishment rounds

The Global Fund fights the major global diseases of HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. It operates in three year cycles, and its sixth will commence in 2020. There will be a pledging conference in less than a month from now, on 10 October. The Global Fund secured pledges of just over $US12 billion in each of its last two replenishments, and is seeking $US14 billion for the next three years. Some major donors (including the United States) have already pledged increases.

The World Bank is the world’s oldest and biggest international fund-raiser. In the last replenishment round it raised $US27 billion from donors for its International Development Association (IDA). That was for the period July 2017 to June 2020. It is now fundraising for its next three years. Two international meetings have already been held and there are two to go, in October and December of this year.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is the regional equivalent of the World Bank. Its concessional arm, the Asian Development Fund (ADF), operates on four year cycles. The last one secured donor funding of $US2.5 billion. The next one will commence in 2021, meaning that the pledging has to be wrapped up in the first half of next year.

Finally, Gavi, the Global Vaccine Alliance, runs on five year funding periods, the last of which started in 2016. It was backed by funding of $US9.3 billion and will conclude in 2020. Gavi will have its third replenishment in 2020, with the new funds to be spent from 2021 onwards. Gavi kicked off its replenishment process at the end of last month. Its major fundraiser will be mid-2020.

Australia’s contributions

Because these organisations are so big, Australia is a fairly minor donor to them, except for the smaller, regional ADF.

In the last World Bank IDA replenishment, we pledged a commitment of $A640 million (see Table 1a, p.143), which made us the twelfth largest donor out of 52. Australia gives less to the ADB’s ADF, but we are a much more important donor. Our $A467 million to the last ADF round made us the second largest donor after Japan (Table 5). Despite aggregate aid cuts, our giving to the Global Fund has actually gone up in recent years. Australia provided $A200 million for both 2011-2013 and 2014-2016, and then $A220 million for 2017-2019. That made us the eleventh biggest donor. Gavi is similar. We are providing $A250 million to Gavi over its current funding round, which again makes us the eleventh largest donor.

(If you want to find out more about Australia’s commitments to each of these four international organisations, check out the “Commitments” page of our Aid Tracker.)

Where are we going to find the money?

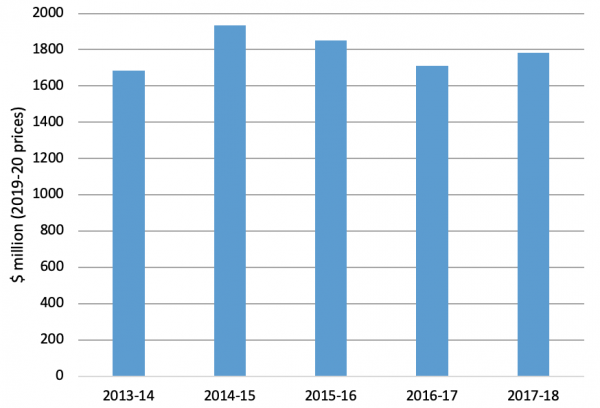

There is a threefold squeeze. First, the overall aid story since 2013 has been one of deep aid cuts. After inflation, the aid budget has been slashed by 27% from 2012-13. Second, aid to the Pacific is on the increase with the Pacific step-up and growing concerns about strategic competition from China. Third, these replenishments rarely ask for less than they got last time.

So far, the Coalition has managed this predicament by cutting aid to Asia (and wiping out aid to Africa) while protecting multilateral spending. As shown below, spending on international organisations has in aggregate been spared the aid cuts in toto.

No aid cuts here: Australian aid delivered to international organisations in recent years

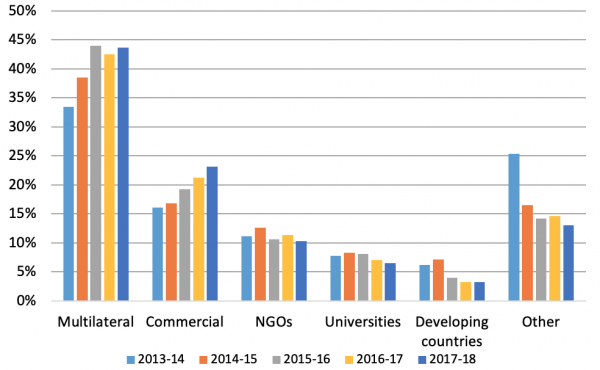

Since international organisations have been spared, it follows that the share of the aid program given to them has increased in recent years. The next graph shows just how dramatic the increase has been. (When Australian NGOs and development contractors came together for the first time to make a statement on aid just before the election, one of the main things they could agree on was that this tendency to give a larger share of our aid to multilaterals was a bad thing.)

Australian aid by delivery partner

What will and should happen?

Can Australia continue to insulate international organisations from its overall aid cuts and its desire to give more aid to the Pacific? This is a hard question to answer. On the one hand, Australia professes an ongoing commitment to multilateralism. This will protect the amounts we provide to the World Bank and the ADB. And the Global Fund and Gavi are politically savvy machines with strong support bases in Australia among MPs.

On the other hand though, entire country programs are now being dismantled in Asia, and the pressure to provide more to the Pacific is inexorable. Without an aggregate aid increase, it is quite likely that the multilaterals will be the next in the chopping line. The World Bank and ADB in particular are easy to discredit as faceless and remote international bureaucracies.

There is an upside. A positive response to the replenishments might force the government’s hand to increase the aid budget. Pledges are made before the start of each funding period, but the money is transferred over that funding period. So, Australia could be bold and make announcements that require an aid increase not now but in the future. After all, after two terms of aid cuts, and with our aid generosity at an all-time low, it is surely time to start rebuilding our aid program.

These replenishments will certainly be testing times for Australia, and the outcomes are uncertain. I’ll end by saying what I think should happen, which is that we should at least maintain our multilateral contributions to the global ones (World Bank/IDA, Global Fund and Gavi). They are all focused on Africa, and, while one can justify a lack of Australian bilateral aid to Africa, it is heartless to think that we should not contribute in a proportional way to global efforts to help the world’s poorest continent. Note that we are typically eleventh- or twelfth-placed in replenishment rankings – on the low side for an economy that is the ninth largest in the OECD, and the eighth richest. We might not aspire to lead multilateral efforts to combat global poverty, but we should not be lagging.

Graphs are from my 2019 aid budget analysis, based on DFAT statistics.

Thanks Stephen, This is a related dilemma facing ACFID in its work to contribute to the review of DFAT’s Country Aid Investment Plans. With dozens of these country plans up for review (nearly all ended in 2018/19) the strategic focus with which to approach this task is blurry. Most of these plans were developed in 2015/16, prior to the Foreign Policy White Paper, and using benchmarks from the Making Performance Count Framework of 2014. A lot of water under the bridge since then. So, yes, I agree with the above posts that generous replenishment of the global health funds is important. But, without an updated policy framework and greater budget predictability for the aid program, it is increasingly challenging to look across the portfolio to inform these case by case assessments and budget decisions.

Thank you Stephen for the timely analysis. A very good article as usual.

There are some small clarifications that might be made with respect to the contribution to the GFATM. The contribution by Australia in 2011-2013 was AUD 199.88m, in 2014-2016 it was AUD 195m (Australia pledged AUD 200m but actually contributed AUD 195m), and for 2017-2019 the pledge is AUD 220m however to date the contribution is AUD 104.6m leaving AUD 115.4m outstanding. Hopefully the outstanding amount will be forwarded by Australia over the next 3 months to honor our pledge!

However, while this may look like Australia has maintained the level of contribution reasonably level over this 9 year period, when one looks at what it has meant in USD terms so that we can compare how we stand against other donors, the contributions have fallen from USD 198,712,176 in 2011-13, USD 177,611,811 in 2014-16 to USD 168,221,440 for 2017-19 assuming that Australia honors its pledge. That is, because of the fall in the AUD against the USD, our contribution in international terms has fallen. This data is freely available on the GFATM website.

With the GFATM replenishment meeting next month, it will be interesting what is announced when other major donors have already announced increased commitments.

Stephen, thank you for highlighting the replenishment of the Global Fund, but why did you not ask the Australian Government to increase its pledge to the Global Fund like everyone else? The ‘maintain’ argument is fine if it is maintain by keeping in step with others: including USA (a 15.6% increase), Germany (17.5%), and UK (16%). With Australia starting from a low base (A$73m p.a.), matching others would require only about an extra A$12-27m per year; a modest contribution to an effective program to help end AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.

Great question Matt! I also think when it comes to health security, we need to be increasing our investments to multilateral programs such as Global Fund, Global Polio Eradication Initiative and Gavi the Vaccine Alliance. I hope Australia really steps up over the coming months as these key replenishments take place. Gavi’s replenishment due in June next year provides us an opportunity to show our regional leadership in ensuring every last child receives a vaccine. These programs are critical in delivering life-saving vaccines and in tacking infectious diseases: a threat that knows no border.