China’s growing global influence has brought competition to development aid, a sector long dominated by several highly developed countries and Western-backed organisations. Once sold as the voluntary burden of the developed world – to lend a helping hand to poor countries – aid is often labelled ineffective, politically self-serving and economically predatory. However, the emergence of China as a donor country is a potentially disruptive event. Does China’s newfound influence – an ideological counterpart to neoliberal developmentalism – presage a sea-change in the aid concept, or will China embrace the same model that has failed for decades? China’s growing infrastructure expertise is an insightful indicator when forecasting its potential impact on development aid.

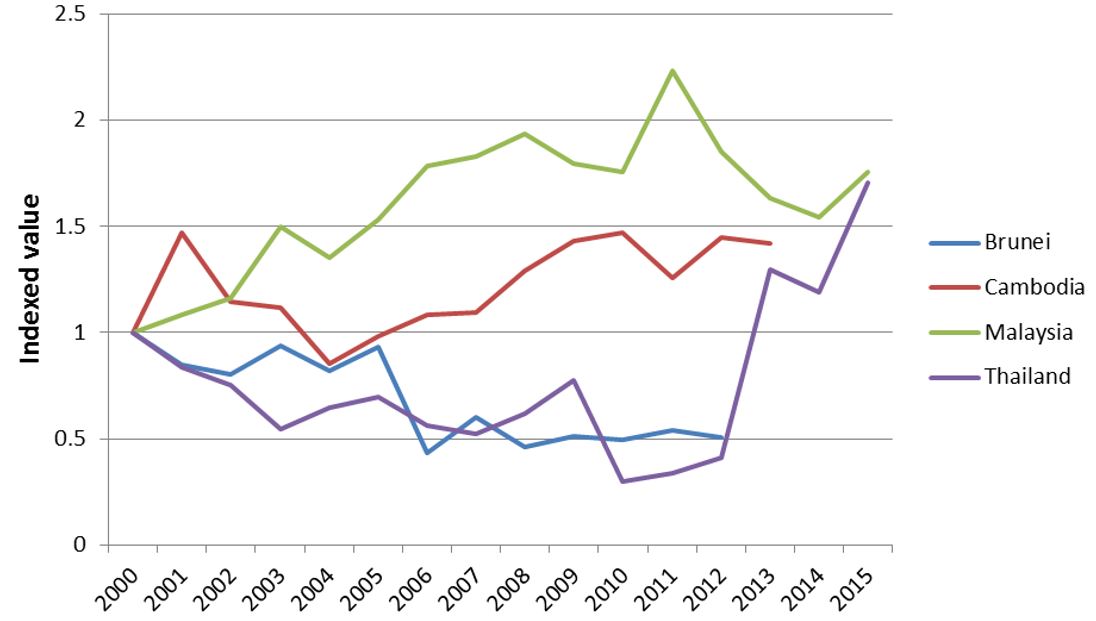

While China is globally preeminent in infrastructure development, since 2000 the ASEAN region’s per capita spending on infrastructure services for transport and communications has been spiky and inconsistent (Charts 1 and 2). Several trends are clear. First, Malaysia and Cambodia adopted moderately stable spending patterns since 2000, although Malaysia has decreased spending since 2011. Second, Thailand was a laggard until 2012, after which spending sharply increased. Finally, China has maintained a relatively consistent and aggressive spending effort since 2007. Unlike most of its regional neighbours, China’s expertise and credibility in infrastructure are borne of the country’s tightly coordinated and decades-long domestic development initiative; the Chinese landscape is a showroom of examples. Operating since 2007, the high-speed rail system now services over 80 per cent of provinces. In the past 15 years, all of China’s major cities have built or renovated airports, and in 2016 China was expected to invest nearly US$12 billion in civil aviation. Such rapid infrastructure growth is not possible without expertise, which is increasingly home-grown and now broadening as domestic infrastructure projects mature into their operational and maintenance phases.

Chart 1: Transport and communications (government service expenditure per capita)

Chart 2: Transport and communications (government service expenditure per capita)

Source data: Asian Development Bank (delimited by national data availability). Yearly data for China can be compared only since 2007 due to revisions in accounting methods.

With this store of expertise, China now views the developing world as a market for infrastructure services via development aid. It appears to have adopted a two-pronged approach: direct intervention through investments in hard infrastructure (targeting South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia) and indirect intervention through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

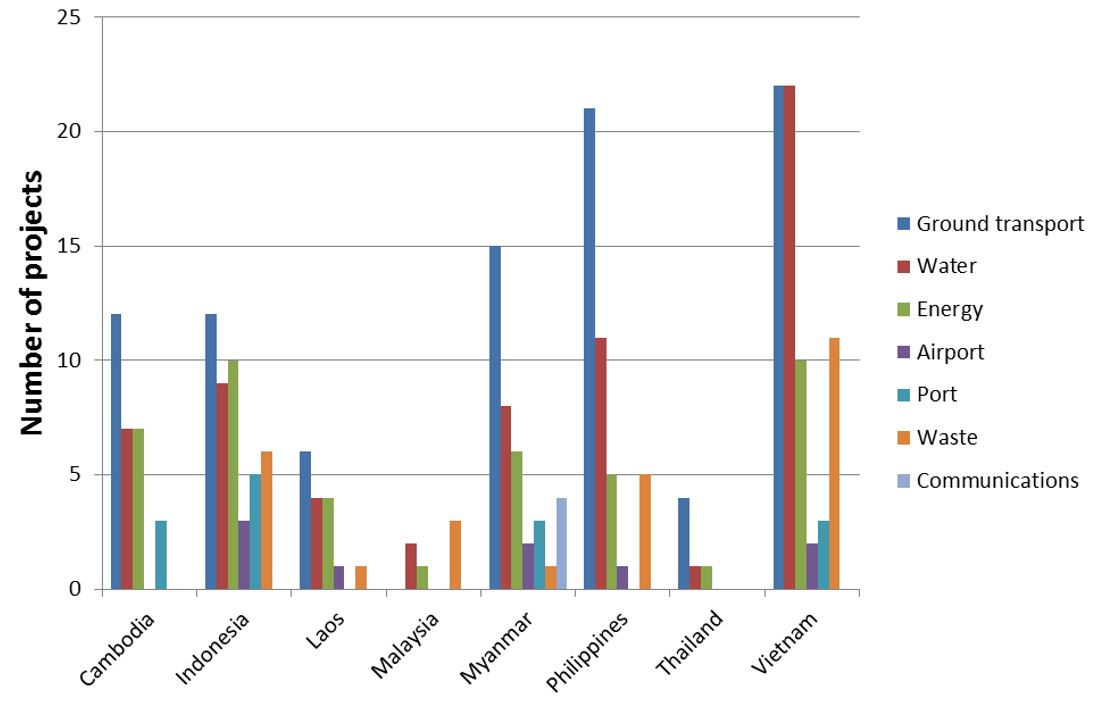

Sitting behind these efforts is geopolitical complexity, now manifest in an infrastructure “proxy war” between China and Japan. The spoils are not only a potentially lucrative portfolio of contracts in Southeast Asia, but also status as the region’s infrastructure export leader for the 21st century. With a long history providing infrastructure services, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) maintains an active role in projects including urban and regional railways, power generation, and water resource management (Chart 3, derived from JICA data). In 2014, JICA was involved in US$5.7 billion worth of projects in the region and is now assisting in India’s first bullet train project valued at US$15 billion.

Chart 3: JICA infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia

Nevertheless, China is chipping away at Japan’s development influence in Southeast Asia. In late 2015, China won a bid for a US$5.5 billion high-speed rail line in Indonesia, beating Japan by promising more peripheral investment. China also proposed a wildly optimistic completion date of 2019. In a region where the development phase for infrastructure projects is often measured in decades rather than years, China’s promise must have seemed both enticing and unrealistic.

Beset with delays in permitting and administrative approvals, the project was predictably halted only one week after the first sod was turned. Some analysts cited a lack of understanding by Chinese managers about the mechanics and realities of doing business in Indonesia, where democratic systems and politicking often stonewall infrastructure progress.

In similar fashion, China has also proposed a US$7 billion rail project for mountainous Laos, part of a regional network linking Kunming with Vientiane (and ultimately Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore). The amount Laos will borrow from China is nearly equal to the landlocked country’s $8 billion annual GDP, adding fiscal stress to an already lengthy list of uncertainties. Enabling conditions such as a unitary developmental administrative apparatus, present in China, are absent in Indonesia and much of Southeast Asia.

China continues to build credibility through image and visibility, having made global headlines for ambitious and “sexy” infrastructure projects like bullet trains and massive dams, the type it hopes to export. JICA, on the other hand, is also involved in a variety of less visible project types including irrigation, waste management, and transport optimisation systems. Further, Japan has found a way to overcome administrative hurdles, even where local conditions lack the efficiency and transparency of Japan’s own. This can be attributed, in part, to decades of experience.

Providing an alternative to long-established aid programs requires focus and discipline. China faces three challenges in becoming a leader in developmental aid. First, China is learning difficult lessons about deploying infrastructure in countries where governments have no experience with such project scale. Will China remain patient as land appropriation, public hearings, regulatory approvals and impact assessments lumber slowly through inept bureaucracies? Second, if a recipient nation’s default risk rises, will China have the will and financial stability to complete projects? Finally, smaller communities impacted by infrastructure projects will win (or lose) big. If they endure the headaches of the development and operational phases to benefit more prosperous regions, will China be prepared to compensate these communities and will domestic governments withstand the inevitable political blowback? In short, China must accommodate vastly diverse national contexts across a growing global portfolio of programs. Expertise in engineering is not enough; China must manage the unpredictability and inefficiency that typifies public works projects in developing countries.

In the development aid world, as in almost any market, competition is healthy. With China’s emergence, Japan is boosting its development budget and softening loan terms. Both can compete on traditional measures like technical and managerial expertise, financial stability, and promises of ancillary investment. However, with technology-enabled political mobilisation growing, public concerns about the negative impacts of projects on individuals, communities, and the environment necessitate substantive policy action. Infrastructure development in an aid context no longer relies only on the state-of-the-art, but on the state of the heart. It is not too late for China to adopt a humanitarian approach while remaking the failed concept of development aid into a 21st century model of efficiency and effectiveness – with “Chinese characteristics.”

Kris Hartley is a Lecturer at Cornell University and a Nonresident Fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. This post is published in collaboration with Policy Forum, Asia and the Pacific’s platform for public policy analysis, debate and discussion.

Leave a Comment