Australia’s 2016 aid budget likely represented an acceleration of a decade-long trend away from country programming in the Australian aid program, as was shown in the first post in this two-part series. Country allocations, already falling as a share of the aid budget ever since 2009-10, and now also way down in absolute terms owing to Coalition aid cuts, will face huge pressure from the global programs side of the budget from 2017.

The 2016 budget savings, totalling $224 million, all came from global programs, and the single largest contribution was made by ‘other multilateral’ programs, which include global health, education and environment partnerships. Commitments to multilateral organisations, the government says, are only temporarily down because the 2016 cuts were achieved mainly by ‘re-profiling’ such commitments across the years.

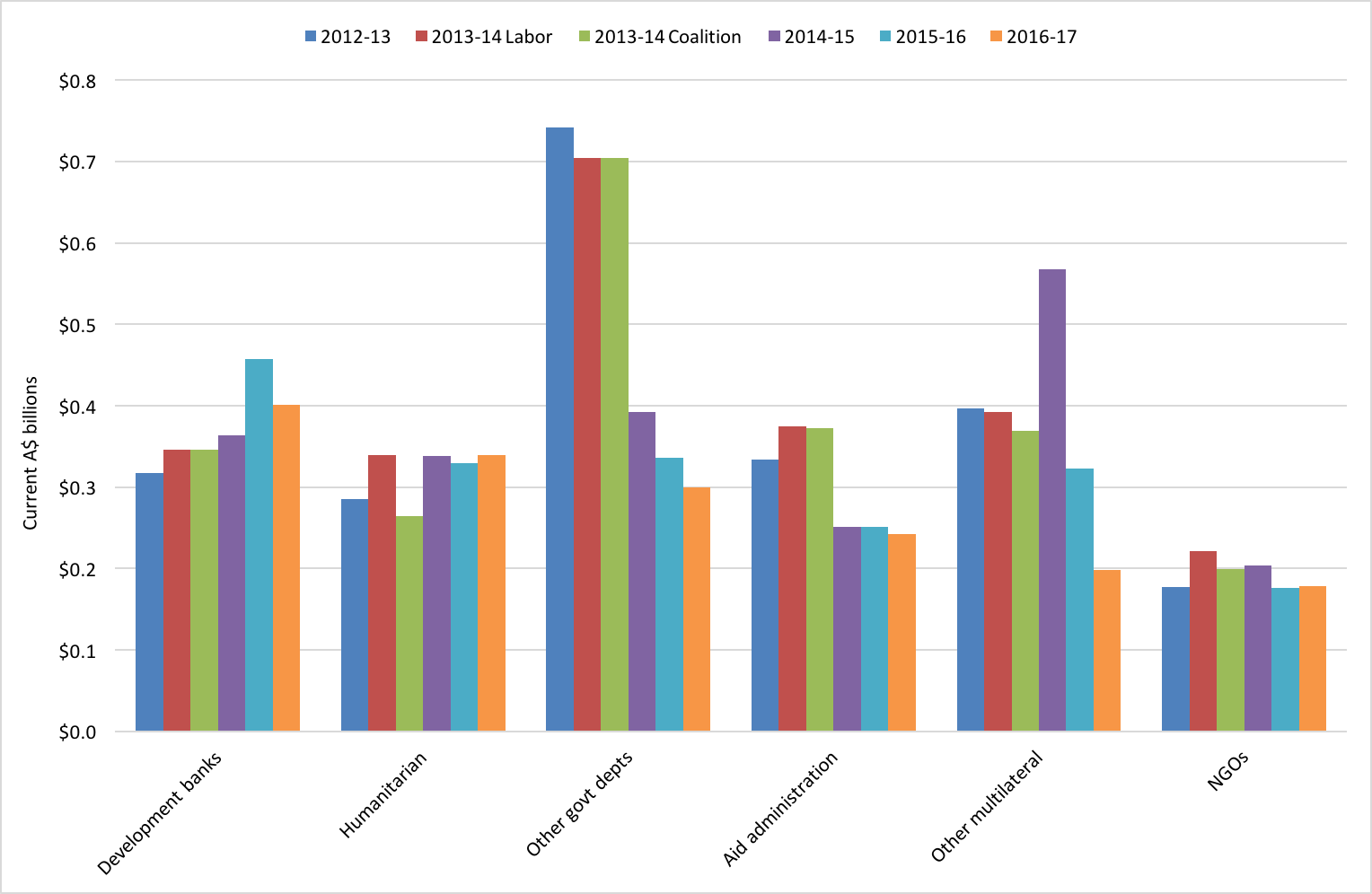

The chart below, which relates to the six main building blocks on the multilateral side of the aid budget, shows exactly where the savings came from, together with trends over the last six budgets (counting the Coalition’s major 2013-14 budget revision as a separate budget).

Australian aid allocations to global programs

The savings came mainly from the part of the budget that any foreign minister would be most loathe to cut. Organisations like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the Gavi Alliance and the Global Partnership for Education are, among other things, formidable money-raising machines. Politicians of all stripes are generally eager to support them. So it is easy to believe that the government will not in fact reduce contributions to these organisations overall, even if it is paying them less this year.

Winners and losers

Regardless of how the government manages to maintain the global programs side of the budget from 2017, it is interesting to consider how the 2016 global program allocations affect its shape, and to put the single-year changes in the context of medium-term trends.

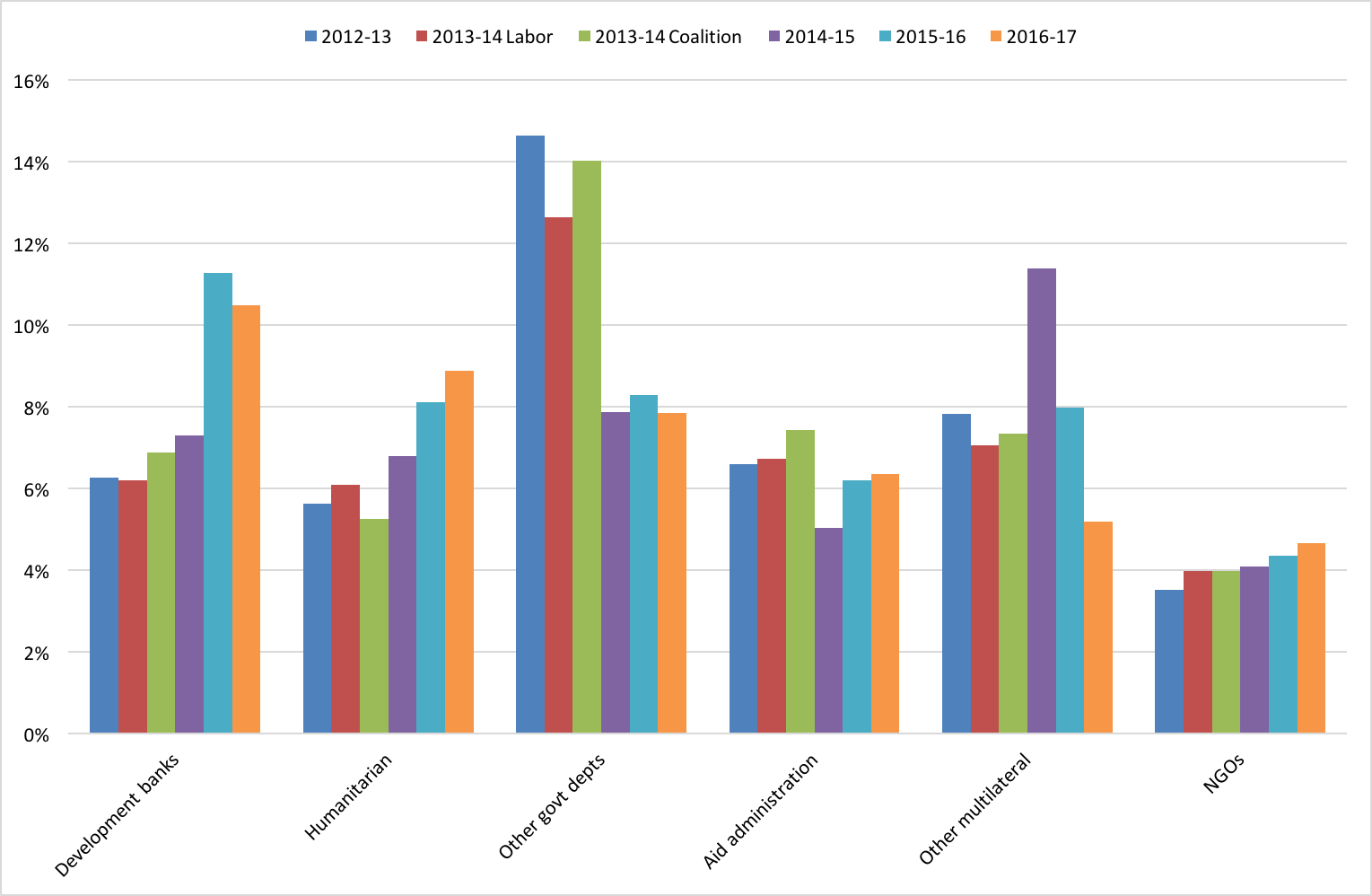

In order to gain a clear view of what is happening on the global side of the budget, it is useful to abstract away from the dollar amounts and consider the building blocks in terms of their shares in the aid program, as in the figure below.

Share of global programs in Australian aid allocations

There was only one significant loser in 2016-17, ‘other multilateral’, but there are several clear winners and losers over the six budgets shown above.

First, after a mis-step in the 2013-14 budget revision, humanitarian aid has grown steadily both in dollar terms and as a share of the program under the Coalition, though Australia still sits below the current OECD average, which is around 11%, on this measure. The dollar amount has grown only a little in 2016-17, and must now accommodate a three-year commitment, announced in the budget, of around $75 million per annum for Syria-related assistance. While the predictability of this commitment is to be applauded, it seems to lock in the peak level of annual funding contributed to humanitarian programs in Syria and Iraq in 2015 (judging from UN contribution data). Any consequent trade-offs over the next few years will need to be made within the humanitarian, emergencies and refugee allocation.

Perhaps related to this, the government has for the first time not disclosed allocations to global humanitarian organisations individually in its main allocations table, but has lumped them together under ‘global humanitarian partnerships’. (The total is a fraction higher than last year.) To find allocations to organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) you have to delve into the latter part of the Orange Book (p. 50). Here you find that WFP’s allocation has fallen $7.5 million to $40 million, with $7.2 million of this shifted to UNHCR and the ICRC. This seems a reasonable rebalancing but it is unclear why individual agency allocations are now being given less prominence.

Second, aid administration as a share of aid spending is now back at the upper end of the usual range for OECD donors, around where it was before the merger in 2013. The allocation has stayed about the same through the last two budgets, despite the huge program cuts.

It should not be assumed, however, that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is spending all or only the $243 million allocated for aid administration for that purpose. The merger has made it impossible for anybody, including DFAT itself, to know how much DFAT really spends on the management of the aid program. It is even possible that the above allocation would not actually cover the costs of the 1,200 or so current positions inherited from the 1,700-strong former Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID). If so, DFAT will have merged the unfunded positions with pre-existing or emerging vacancies. To the extent that this has saved the jobs of some former AusAID staff, that is a good thing. However, it is problematic that there is no longer any way of getting even a rough handle on how efficiently the aid program is run.

Third, other government departments’ share in the aid program is declining. When one looks at the details, this is largely but not only because Australia has ceased incurring onshore asylum-seeker costs in the last two years. The share has almost halved since 2012-13, to 8%. Again, this could be viewed as ironic given that transferring the aid function to DFAT was meant to ensure greater alignment between aid and Australia’s ‘international policy agenda’.

There is, however, one winner among other government departments. The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), which is included in that category but sits within the same portfolio as DFAT, saw a funding increase of over $10 million to $103.4 million in the 2016-17 budget. It is not easy to see any reason for this in the current budget context, aside from foreign minister Julie Bishop’s feeling that ACIAR is the jewel in the crown of her portfolio.

Emerging pressures

An earlier, pre-budget post pointed to three potential new sources of pressure on Australia’s straitjacketed aid budget, as discussed below. These, like the deferred commitments discussed above, are pressures that come mainly from the global programs side of the budget. None were explicitly realised in the budget, but neither has any disappeared.

Climate change. Climate change financing was the least of the pressures, and in 2016-17 is being held to the undemanding floor level of $200 million which is required to deliver on the Prime Minister’s December 2015 pledge in Paris. As noted previously, this game could get harder as negotiations proceed in the UN context on what can and cannot be counted as climate finance.

Refugees. There is no indication in the budget documents that any costs associated with the 12,000 Syrian and Iraqi refugees (in practice, it seems, they tend to be Iraqi Christians) whom Australia has pledged to resettle are being thought about as a charge to the aid budget. At the same time, Australia has barely processed any refugees at this point—the latest estimate is just 180 people—so this question might arise more forcefully as time goes on.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The budget papers contain no obvious provisions for DFAT or any other department to meet the cost of Australia’s paid-in capital subscription to this new institution. The cost, according to the December 2015 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, will be close to $1 billion over five years. It is very likely to be an eligible charge to the aid program, despite premature suggestions to the contrary by DFAT. The DFAT forward estimates in Budget Paper 1 include some huge, lumpy add-ons for 2016-17 and 2019-20, about which they say:

The increase in Foreign Aid spending in 2016-17 and 2019-20 reflects renewed multi-year funding commitments to multilateral funds such as the Asian Development Fund and the World Bank’s International Development Association.

The figure for this year is $520 million above that for 2015-16; the figure for 2019-20 is more than $1 billion higher. These amounts are hard to interpret, and to compound the problem the DFAT forward estimates do not correspond to the Official Development Assistance budget. (They use accrual rather than cash accounting and leave out non-DFAT expenses.) Nevertheless, a capacity to meet future AIIB costs could be buried within these forward estimates. Undoubtedly any cash payments will be pushed as far out in time as possible, but this potential budget pressure remains even if, like other multilateral pressures, it has been put on the never-never.

Overall, the global programs side of the budget is now deeply in the red, and the internal aid budget balance can only be repaired by increasing the budget or subtracting funds from country programs. The latter course is currently much the more likely. Given a static budget, reducing bilateral allocations is in fact preferable to reducing multilateral allocations, and the other building blocks on the global programs side of the budget either should not or realistically could not go much lower. Australia should be a generous supporter of global programs, much more generous than it is. Sir Gordon Jackson might not agree, but he is history.

Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Leave a Comment