Papua New Guinea’s Tuition Fee-Free policy: is it working?

By Grant Walton, Anthony Swan and Stephen Howes

10 December 2014

In our previous blog post we looked at Papua New Guinea’s attempts to instigate fee-free education policies since independence. We suggested that the 2012 Tuition Fee-Free (TFF) policy – the fourth attempt to introduce ‘free education’ – has been more clearly communicated, better organised and funded, and has lasted longer than previous policies. In this post we draw on the findings of our recent research, to examine the TFF policy’s implementation and performance more closely.

How well is the TFF policy being implemented?

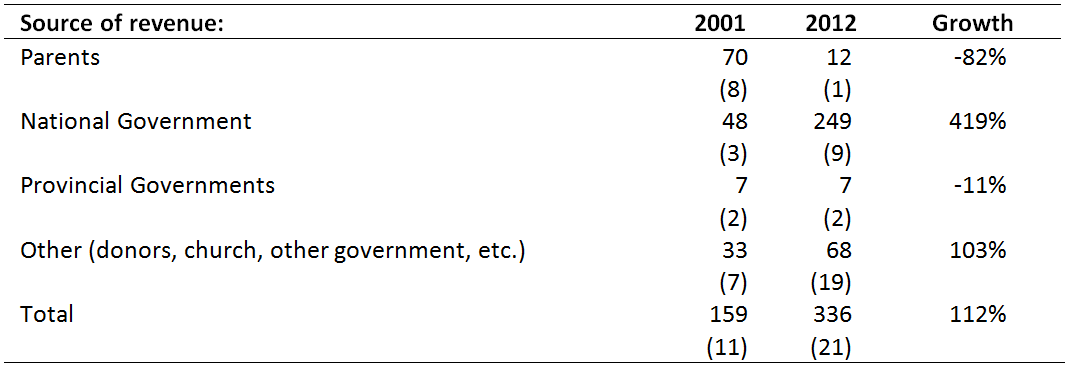

Our findings suggest that schools received most of their subsidy, and that this has helped to compensate schools for a loss of revenue over the decade. Between 2001 and 2012, national government subsidies increased from 48 to 249 kina per student, 21 kina short of the 270 kina per enrolled student that these schools are meant to get. (The shortfall is likely due to the fact that about 16 per cent of the schools we surveyed had not received their second payment, and about 10 per cent had not received a payment at all.) This increase more than made up for the loss of revenue from parents: support from parents dropped from 70 to 12 kina between 2001 and 2012. As a result, the total revenue per student was 336 kina per student in 2012, more than double the 2001 figure.

Revenues per student 2001 and 2012 in 2012 prices

Notes: Standard errors in parenthesis.

Notes: Standard errors in parenthesis.

This in itself is an achievement. A World Bank review of free education policies in Africa found that in some cases replacement revenues did not sufficiently make up for revenues lost. By and large this has not been the case in PNG.

Having said this, remote schools face excessive costs associated with accessing their subsidy. For the 216 primary level schools in our 2012 PEPE survey, on average it cost over 1,100 kina to access the subsidy, or about 4 per cent of the overall subsidy amount. In Gulf province, which is particularly remote, the reported average cost was 2,865 kina per school or 32 per cent of the average subsidy payment. Not only are travel and associated costs expensive, but there are substantial risks to transporting large sums of cash from banks to schools.

To work effectively the TFF policy requires oversight from both the government and the school community. The government funds Standards Officers and other district officers to monitor school expenditure – including subsidy payments – and school quality. The Department of Education’s TFF Policy Management Manual instructs Board of Management Chairs and Head Teachers to meet with district authorities twice a year to ensure they are using the TFF funding correctly. Results from the survey suggest that the department’s target is not close to being met. Only 29 per cent of schools said they received a visit to check the subsidy payment in 2011, and 33 per cent said they received a visit in 2012. In 2011 or 2012 only 39 per cent received a visit. This suggests that in both years inspections mostly occurred in the same schools.

As we outlined in our last post, there are signs that the community is playing an increased role in monitoring school subsidies. Still, this is not enough to make up for the infrequency of government monitoring. More needs to be done to ensure that education officials are actively monitoring subsidy payments; and at the very least, that they visit different schools every year, rather than the same schools as at present.

Is the TFF meeting its objectives?

The TFF has five key objectives: to improve access to schools (especially for girls); improve retention; improve the quality of education; strengthen education management; and improve equity to schooling across the country. Our findings give us insights into the policy’s impact on three of these objectives: access, quality of education and equity.

The TFF has led to an improvement in school enrolments. Between 2011 and 2012 enrolments increased by 17 per cent, the same percentage increase that our analysis suggests occurred in the 2002 attempt at introducing free education. There are two important conclusions to draw from the large changes over the two time periods. First, the magnitude of these increases in enrolments in a single year is large, given an average annual increase in the PNG population of around 3 per cent and an average annual increase in enrolments between 2002 and 2011 of 4.6 per cent. Second, the increase in enrolments in 2012 is particularly impressive since it is from a higher base.

These gains are, however, being undermined by reducing attendance levels. In 2002, 84 per cent of students were present on the day of the survey (based on Grade 5 students), this dropped to 71 in 2012. This is likely due to schools inflating enrolment figures, as well as enrolled students giving up on their education due to quality concerns (as we explore below). Still, overall more children are now attending school: in 2002, 62 per cent of parents said that most or all children in their community attended school, by 2012 that figure rose to 70 per cent.

It’s too early to assess the impact the TFF has had on girls’ enrolments. But the long term trend looks promising – only one third of the shared total enrolments in 2002 were girls, compared to 46 per cent in 2012.

In more good news, we find that the TFF has contributed to greater equity by substantially lowering the cost of education. Estimates of the total cost of schooling per student (including tuition fees, project fees and additional costs) reduced from 131 to 39 kina on average. These savings benefit the poor. According to the 2009-10 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, 33 per cent of parents said their children were not going to school because of fees, by far the most common reason. The figure was 35 per cent for parents who had girls and 50 per cent for those in the poorest wealth quintile of families.

These achievements are tempered by the impact that the TFF has had on the ability of schools to provide quality education. The TFF has certainly contributed to this overcrowding, which makes the Department of Education’s official goal to reduce classes with more than 45 students to zero by 2019 difficult.

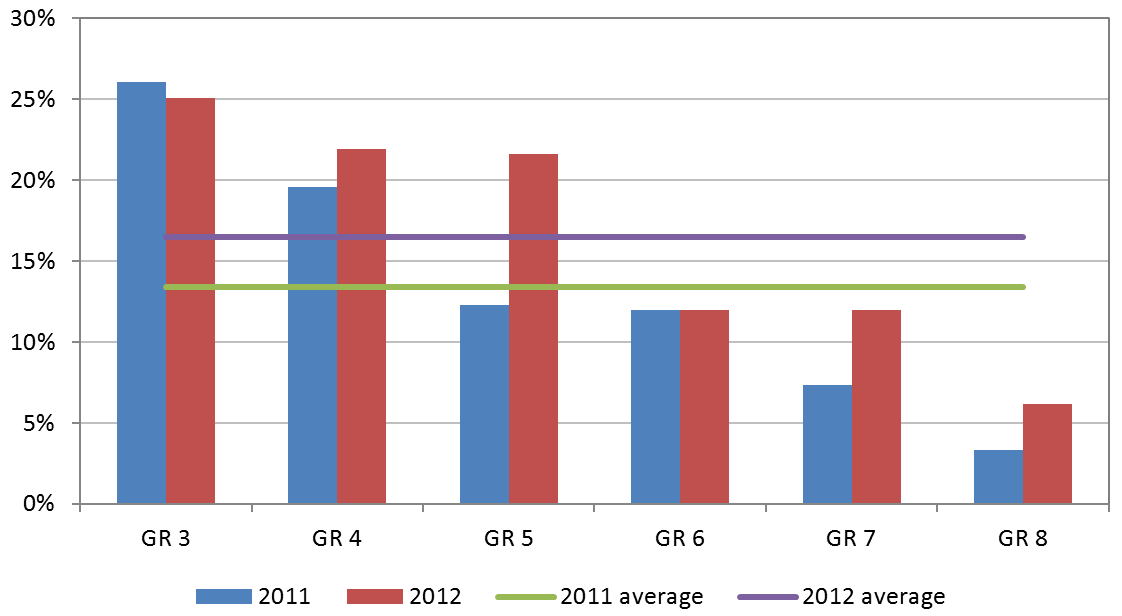

The graph below shows that the share of classes with more than 45 students has increased in 2012 relative to 2011, and that growth has been particularly high in Grade 5, 7 and 8. In 2012, the level of crowding was, in both years, worse for lower primary grades.

Share of classes with more than 45 students

Source: Based on survey with Head Teachers and, where there are missing values, statistics from the National Department of Education.

Some conclusions

While it is early days, the TFF policy shows a number of indicators of success. Schools are receiving subsidy payments, more students are accessing schools, and education costs have reduced. However, these initial achievements are threatened by poor monitoring, overcrowding, high costs for remote schools, and poor attendance. And the TFF on its own does not directly address other factors that contribute to poor educational outcomes, such as the quality and quantity of teachers.

We outline a number of recommendations for addressing these issues in Chapter 5 [PDF] of the report. In particular, we call for increasing teacher numbers to address overcrowding; better support for government officials and community representatives who can monitor the policy; and better targeting of the subsidy (which would mean increasing subsidies to remote schools, and reducing it for better off schools). Overall, the focus needs to shift from quantity (getting more students to enrol) to quality. Addressing these issues will go a long way towards improving the educational environment of schools across PNG.

The report ‘A lost decade? Service delivery and reforms in Papua New Guinea 2002-2012’ will be launched in Canberra at 12.30pm on Thursday 11 December at the ANU. Speakers will include NRI Director Dr Thomas Webster. Register for the event here.

Grant Walton and Anthony Swan are Research Fellows at the Development Policy Centre. Stephen Howes is Director of the Centre.

About the author/s

Grant Walton

Grant Walton is an associate professor at the Development Policy Centre and the author of Anti-Corruption and its Discontents: Local, National and International Perspectives on Corruption in Papua New Guinea.

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.