Bins of apples at Otherwood Orchards, South Australia (Apple and Pear Australia Ltd/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

Seasonal Worker Programme: bigger and better in 2016-17

By Stephen Howes and Sachini Muller

8 January 2018

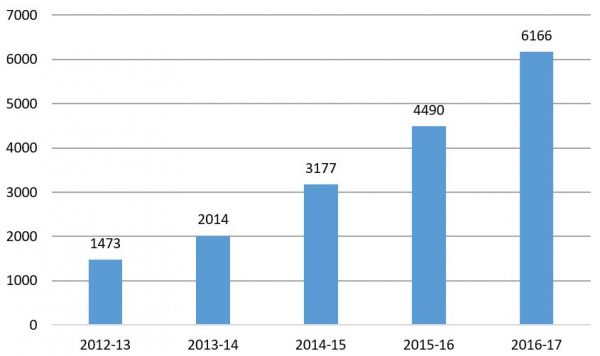

Data released by the Department of Employment indicate that it has been another year of rapid growth for the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP). Growth was down from the 50% of 2015-16, but still high at 37%.

Seasonal Worker Programme visa numbers

Rapid SWP growth may be a result of a fall in backpacker numbers, moves by state governments and supermarkets to more tightly regulate horticultural labour (which favour use of more regulated schemes like the SWP), and good feedback from those farmers using the scheme. On the supply side, there is no shortage of Pacific islanders wanting to participate in the scheme, with potential participants vastly outstripping the number of jobs made available by employers.

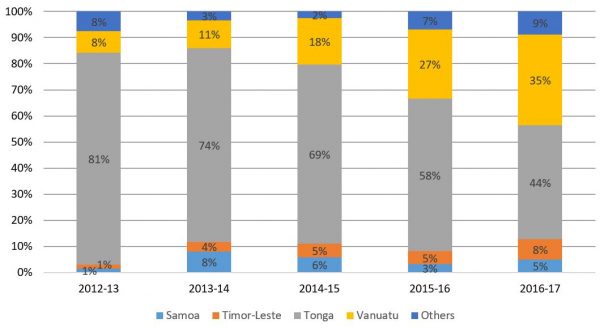

As well as growing in size, the SWP is becoming more diverse. In 2012-13, 81% of workers were from Tonga. That figure is now down to 44%. More than half the growth in the number of workers in 2016-17 was due to Vanuatu, whose share is now 35%. Timor Leste and Samoa are in third and fourth place respectively, and together the top four countries send more than 90% of all SWP workers. Some of the miscellaneous “other” countries did have a good year (PNG grew from 42 to 139, Kiribati from 20 to 124), but off a very low base.

Seasonal Worker Programme country composition

The percentage of return workers was steady at about two-thirds of the previous year’s number of workers, indicating both the preference of employers for returning workers, and the desire of most workers to return.

Seasonal Worker Programme percentage of return workers

Note: Percentage is of workers coming in the previous year.

The share of female workers has remained stable over the last five years at just under 15%. PNG and Timor Leste currently do the best for gender equity (just under 30%), Samoa and Solomon Islands the worst (3% and zero, respectively). No countries show a sustained improvement in gender equity over time. The small improvement in gender equity since 2013-14 is due to a switch away from Tonga (low equity) to Timor and Vanuatu (higher equity). In 2016-17, Vanuatu managed to send nearly 100 more women workers than Tonga despite having 540 workers fewer in total.

Percentage of female workers by sending country and for all

While or perhaps because it continues to grow, the SWP continues to attract bad publicity. Late last year, the Weekly Times ran a story on the fact that 12 SWP workers have died while in Australia since 2012. While the Government clarified that none had died on the job (five were in two car accidents), the article implied that at least some of the deaths were due to poor living conditions. All of these deaths are a tragedy. Clearly more needs to be done to ensure that only healthy workers are sent to Australia, and, regardless of the causes of these deaths, to clean up the horticultural sector. But the SWP is part of the answer, not the problem. The major research report on the SWP in 2017 was the University of Adelaide’s Sustainable solutions: the future of labour supply in the Australian vegetable industry. One of its major findings was that the “The SWP results in less exploitation of workers … when compared with other low-skilled visa pathways”, especially backpackers (emphasis added).

Also completed in 2017, and to be released in early 2018, is a new World Bank study Maximizing the development impacts from temporary migration: recommendations for Australia’s SWP. The Bank interviewed some 400 Pacific seasonal workers in Australia, and asked them how satisfied they were with their experience. On a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 is ‘not at all satisfied’ and 10 is ‘extremely satisfied’, the average was 8.6. For Tonga, the largest sending country, the average was 9.9.

Despite its rapid growth in recent years, SWP expansion should have a long way to run. It is still much smaller than New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employer Scheme (which is now capped at 10,500 workers per year), and much smaller than the number of backpackers working on Australian farms (approximately 40,000). In the Devpolicy-World Bank 2016 Pacific Possible report on labour mobility, we projected that with reforms, the uncapped SWP could reach 40,000 by 2040. That would be achieved with two decades of the absolute increase seen this year. The SWP is still being held back by red tape, but this year’s encouraging results and the farmer-friendly SWP reforms just announced suggest that our optimistic long-term projections may not have been totally unrealistic.

Note: Graphs and data available here.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.

Sachini Muller

Sachini Muller was a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. She is currently completing a Master of Globalisation at ANU.