In setting out the Australian government’s aid budget for 2018/2019, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop, and the Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, wrote: “Our region is home to 40 % of natural disasters and 84 % of people affected by natural disasters worldwide. Our development program is one of the ways Australia can respond to these pressures. In this context, the development program is more important for Australia than it has ever been.”

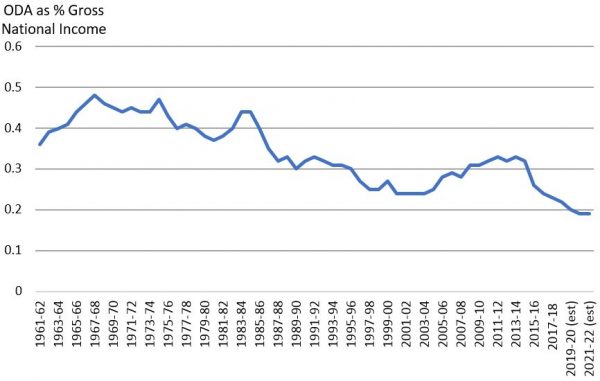

Why, then, if the development program is more important to Australia than it has ever been, has the Australian government aid program (Official Development Assistance or ODA) now fallen to the lowest level as a share of GDP ever, as shown in the graph below? Put simply, if the Australian economy was $100 we now contribute just 22 cents in overseas aid.

Source: Aid Tracker

One possible explanation, originally stated by Foreign Minister Bishop, is that cuts to the aid budget are needed to help repair the deficit and debt challenge in Australia. But the Australian aid budget is less than 1% of government expenditure: cutting it is simply not going to make any meaningful difference to the deficit. Furthermore, if reducing the budget deficit was the real reason for the cuts, why has the aid budget been cut by 32% in real (adjusted for inflation) terms since 2012/13, yet much larger government expenditure overall actually increased over that period by 31%? For every dollar of aid, Australia now spends $42 just on health and social welfare in Australia; independent think-tank The Australian Institute now rightly asks if charity now not only begins, but also ends, at home. Analysis by the Development Policy Centre shows that Australia is currently on track to spend more than $10 on defence for every $1 it spends on aid, reversing the age-old vision of turning swords into ploughshares.

A second possible explanation for the decline is that perhaps Australia’s aid program is not particularly effective. But the Australian government’s own latest annual report on the aid program found that nine of ten strategic targets set by the government had been met, including reducing poverty; engaging the private sector in both Australia and overseas; achieving value for money; and combatting corruption. The only strategic target not yet met (empowering women and girls) is nevertheless making substantial progress.

A well-designed and well-managed aid program not only saves lives but saves public money. Smallpox was eradicated in 1980, something that was only achieved through global cooperation and aid programs. As a result, the US government every 26 days saves what it formerly had to spend every year on vaccinating and treating the disease. Australian advisers have helped increase tax revenue in the Solomon Islands from $370 million to $1.34 billion between 2003-2011, thereby enabling the Solomon Islands to become less reliant on aid over time. Similarly, Australian aid for tax reform helped the Philippines generate an additional US$1.18 billion in 2013. Australian aid, in combination with multilateral agencies, also helped Kiribati’s total revenue to more than double between 2014 and 2017.

A third possible explanation for the historic decline in Australian aid is that economic growth in Asia has reduced the need for aid. But World Bank figures show that 327 million people in Asia and the Pacific live in extreme poverty (less than $US 1.90 per person per day) including more than 20 million in neighbouring Indonesia. Public expenditure on health in Myanmar is just $US 13 per person per year. Papua New Guinea has the fourth highest rate of stunting (short for age due to malnutrition) in the world. Less than half of people in Cambodia, PNG, and Solomon Islands have access to electricity. Cutting aid can only hurt the poorest and most vulnerable in our region.

The Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, says there is simply a lack of support for Australian aid among Australians. When asked to nominate suggested cuts to the budget, surveys do show a preference for cutting aid programs. But three-quarters of Australians surveyed approve or strongly approve of Australia giving foreign aid to poorer countries. Less than half (40%) of Australians surveyed think Australia gives “too much” aid. But here is the most important point: few people know the actual size of the aid program. Only 13% of Australians surveyed correctly understood that Australian aid is less than 1% of government expenditure.

Given our geographic location, there are few, if any, other countries in the world that have more at stake in having a properly funded and well-managed aid program than Australia. We need to regain Australia’s role and reputation as a trusted and reliable development partner in the region and globally.

Leave a Comment