As discussed in this blog, I recently helped launch a report on Papua New Guinean perceptions of corruption. The report focused on findings from a household study undertaken in 2010/11. Preceding this study, in 2008, I was engaged by Transparency International PNG – who were funded by the agency formally known as AusAID – to conduct focus groups in rural locations in Madang, Southern Highlands, East New Britain and Milne Bay provinces. The aim of the research was to better understand citizens’ understandings of corruption. We conducted 64 focus groups with 495 people in two locations in each province: one remote and one close to resources. The results of these focus groups informed the larger household study.

This blog summarises the findings from focus groups, and reflects on what they mean for addressing corruption in PNG.

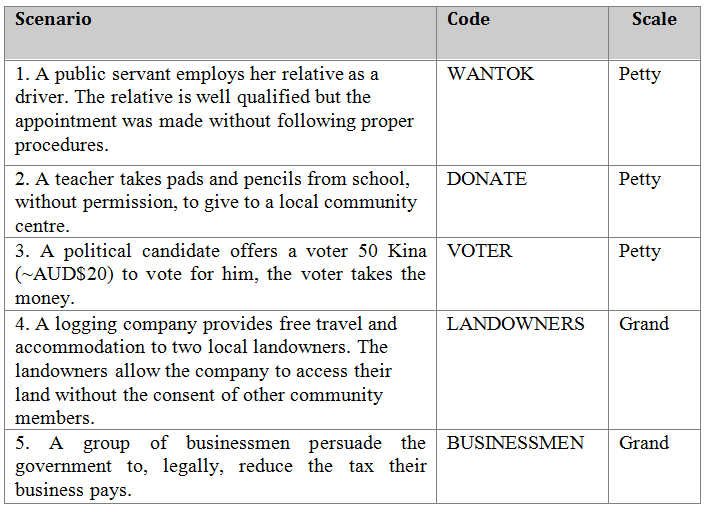

Focus group participants were asked a range of questions; this included responding to five scenarios that represent different scales and types of possible corruption. As shown in Table 1, three scenarios represented possible petty corruption while two represented possible grand corruption. Scenarios involved public officials, the private sector and citizenry, and featured embezzlement, abuse of power, bribery and nepotism. Respondents were presented with these scenarios and asked: 1) if the type of activity mentioned occurs in PNG and why it does or does not; 2) what they thought about the actors mentioned in the scenarios; and 3) what they believed the consequences of such scenarios would be.

Table 1: Scenarios

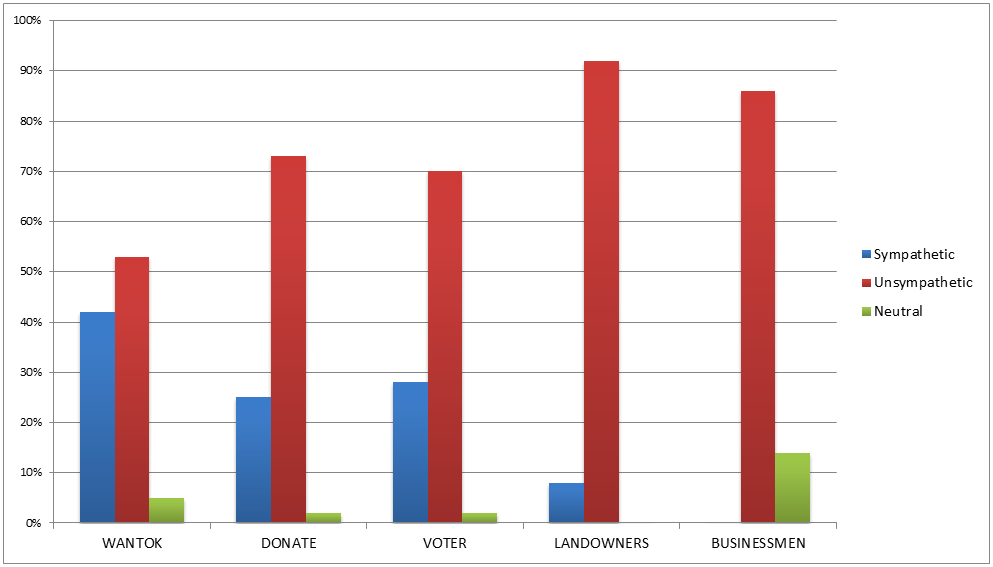

When analysing the results, focus groups were categorised by whether or not respondents were sympathetic to one or more of the respondents depicted in the scenarios. As Figure 1 illustrates, most were not sympathetic. However, there were significant differences between responses to scenarios suggesting different scales of corruption; more focus groups were sympathetic to those engaged in petty corruption.

When analysing the results, focus groups were categorised by whether or not respondents were sympathetic to one or more of the respondents depicted in the scenarios. As Figure 1 illustrates, most were not sympathetic. However, there were significant differences between responses to scenarios suggesting different scales of corruption; more focus groups were sympathetic to those engaged in petty corruption.

Figure 1: Responses to scenarios

Unsympathetic respondents rallied against what they saw as the transgression of rules and laws. This was particularly the case with the Wantok scenario, with respondents – particularly those with higher levels of education – concerned that the public servant knowingly abused the official appointment process. As a result, one male from Milne Bay said, ‘if I missed out on this [job] I would be angry… it’s not right’. Respondents were also concerned about the impacts such transactions could have on their communities. In response to the Donate scenario, a young male in his twenties from Madang, said such acts, ‘deprive children of learning’. A female in Milne Bay feared that ‘the school will run out of materials and [children] will give up school’.

Unsympathetic respondents rallied against what they saw as the transgression of rules and laws. This was particularly the case with the Wantok scenario, with respondents – particularly those with higher levels of education – concerned that the public servant knowingly abused the official appointment process. As a result, one male from Milne Bay said, ‘if I missed out on this [job] I would be angry… it’s not right’. Respondents were also concerned about the impacts such transactions could have on their communities. In response to the Donate scenario, a young male in his twenties from Madang, said such acts, ‘deprive children of learning’. A female in Milne Bay feared that ‘the school will run out of materials and [children] will give up school’.

Responses to both scenarios depicting grand corruption were overwhelmingly unsympathetic. Most responding to the Landowner scenario were concerned about negative social and environmental consequences. For example, a male in Madang, said, ‘this is happening now to us, the company has destroyed our natural resources, we have nothing’. Responding to the Businessman scenario, respondents feared a reduction of social services, and that the company would increase the price of their goods regardless. In other words they believed they would see no benefit from the business having a lower tax rate.

Unsympathetic respondents were, at times, passionate about disciplining those involved in the scenarios. They spoke of taking wrongdoers to court (although many doubted the effectiveness of this strategy) and even beating them up.

Sympathetic respondents highlighted the social, cultural and economic factors that shape such transactions. Many suggested that scenarios reflecting possible petty corruption could help address poverty. One male from East New Britain said that the public official’s relative employed in the Wantok scenario was likely poor and that getting a job, no matter what the circumstances, meant they ‘could now eat rice’.

Some believed the scenarios could redistribute state resources. Responding to the Voter scenario, a male from Southern Highlands, summed up this position, saying, ‘such bribes should be given to the whole community and leaders so every one benefits and not only a few people’. Respondents also spoke about the importance of kinship ties. Responding to the Wantok scenario, a man from the Southern Highlands said the public official was right to employ her relative as she was acting out of ‘traditional obligations’, and rightly supporting a member of her tribe.

Females, those who identified as illiterate, and those from the most remote villages were most likely to sympathise with scenarios depicting petty corruption. It was these groups who were least likely to understand state rules and laws, and expressed concern that they were excluded from state resources.

Conclusions emanating from this research are discussed in length elsewhere (see pay-walled article here; and online report here), for the purpose of this blog I’ll conclude with two points. First, understanding corruption in PNG means acknowledging the context in which these transactions occur. There is a tendency in the corruption literature and the policy documents of donors to view all forms of ‘corruption’ in a normative light: corruption is considered immoral behaviour that can only lead to dysfunctional outcomes. While most respondents supported this view, sympathetic respondents highlighted how social, economic and cultural factors play an important role in attitudes towards (particularly small-scale) corruption in PNG.

This suggests that ignoring how marginalised communities can benefit from corrupt transactions, in the midst of a weak state, can misrepresent the problem and overlook the reasons for citizens supporting those who engage in corruption.

Second, findings suggest that mitigating corruption in PNG will require a broad range of approaches. With some respondents unsure about the laws and rules that applied to the scenarios, it is important to educate citizens about the law, as well as their rights and responsibilities (proper voting practices, for example). Many unsympathetic respondents were keenly concerned about the activities depicted in the scenarios and suggested that they would take action against those involved. This suggests it is important to improve mechanisms for reporting corruption and to support those who are willing to report it.

However, responses also suggest that there are constraints on collective action against corruption. In rural settings where there are strong cultural ties and a weak state, supporting corruption can make sense. Given this, encouraging collective action against corruption in PNG remains a key challenge for policy makers.

There’s no quick fix to this challenge; but here’s a couple of ideas that might help. First, encouraging collective action could mean working with communities to demonstrate how, by following due process, the entire community – particularly the poor and marginalised – can tangibly benefit from developmental processes. This could include mobilising communities to keep the development actors accountable when providing health, education and infrastructure (as explored in this blog).

It may also require encouraging cultural practices that deter corruption and support openness and transparency. This approach has been taken by the PNG Department of Personnel Management, which has drawn on local and Western ethical frameworks to develop their new Leadership Capabilities Framework (highlighted in this blog). The effectiveness of this program is still not clear, but such approaches are important for discovering how culture might augment anti-corruption efforts.

Some fear that highlighting structural constraints (such as the impacts of culture and poverty) in debates about corruption, can excuse corrupt behaviour. However, not acknowledging these factors runs the risk of misunderstanding the problem of corruption, and failing to meaningfully address it.

This blog is based on a recently published article (pay-walled) in the journal Public Administration and Development and a preliminary findings report [pdf] published by Transparency International.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

Wantok affiliation or as most would like to call it “wantok system” has been taking a lot of bashing because of its linkage to acts systematised as corrupt practises. I think there is a reckoned divide on the accepted definition of corruption according to the external ‘citadels of the rule’ that determine what is corruption and what is not.

So another question that could be posed is “What makes corruption or acts perceived to be corrupt sometimes makes sense?” If it makes SENSE…does that mean the attributed sensibility is wrong? The most obvious ‘on the fence’ response would “Well it depends!” Context, context, context…It’s all contextual…What is perceived as wrong in another society might not be in other settings…

Hi Edward,

Nice to hear from you.

I’m with you on the importance of context. Although there are also many similarities in the way Papua New Guineans and Westerners understand corruption. It’s worth remembering that most respondents were unsympathetic to the scenarios. I think that it is important to understand these similarities when seeking to engage citizens in the fight against corruption.

Cheers,

Grant

Hi Grant & Jen

I guess I was not quite clear on what I intended to say regarding the wantok system. Like any other system there are gaps or loop holes that can be exploited by the unscrupulous for personal gain. It is very easy as in most instances to say “its the wantok system”.

For example, if a public servant illegitimately took public money (somehow) and gives it to a brother, sister, uncle, aunty, sister-in-law or brother-in-law to build a copra shed, the most likely reaction to this act will be? It’s the wantok system! Now, is that right?

If a public servant illegitimately took public money (somehow) and gives it to a foreign national of no blood ties with the public servant to finance a business interest. How will you react?

Will you react the same if the foreign national is married to a relative of the public servant? Most certainly the family ties will get more attention!

So what’s more important? the act of committing corruption or doing wrong? the socio-economic circumstances surrounding the act? or both?

Just remember what is called wantok system is unregulated!

Can wantok system be seen as a positive combination of resources through affinity to achieve a greater communal good? If wantok system has been a sustainable livelihood mechanism for the Melanesian societies of the Pacific is there room to explore further on how it can be adopted as a sustainable development model?

I believe there is more positive to wantok system that development partners and the wider donor community could harness.

Cheers

Edd

Hi Edward

Social networks are important and underpin our communities. I wanted to clarify that my comment didn’t intend any disrespect toward the wantok system. As you’ve said, it does come down to the context – the context in which a network is operating and how the it’s being utilised.

Cheers

Jen

Hi Grant

You make a good point that corruption is anchored in a cultural, economic and social context that needs to be unpacked to appreciate how people perceive, understand, process and justify corruption. If we’re taking a zero tolerance standpoint on corruption, how can we expect corruption to be effectively addressed without fully considering and understanding the audience that the anti-corruption message needs to go to?

I agree with Michael that the participants’ perceptions of corruption are possibly attributable to their proximity and likeness to the person benefiting from the actions. If a wantok got the participant their job, then they would perceive a similar story as a lesser crime. (Its a self-fulfilling prophecy – ‘My wantok got my husband a job and we’re good people and not corrupt, therefore its true that…’).

I find the participants’ perspectives about corruption addressing poverty and as a channel for redistributing resources incredibly interesting. We’ve heard this before haven’t we? … Remember that guy that was perceived favorably in western communities… Robin Hood…

This is interesting research. I’m looking forward to reading the article in full.

Jen

Thanks Jen, interesting comments.

Some of the responses do suggest a kind of Robin Hood approach to redistributing gains from corruption, although I most condemned all forms of corruption. I might just borrow the Robin Hood concept for upcoming papers though…hope you don’t mind…it’s rather catchy. Thanks!!

Grant

Hi Grant

You’re most welcome to use the Robin Hood analogy :). By framing it with a legend familiar to our culture, I think it makes it easier to relate/understand others’ perceptions.

Cheers

Jen

Grant,

Thanks for the article.

I may in a way be “taking the bait”, but I have to disagree with the notion that corruption can be beneficial. The notion that corruption can help as long as it benefits marginalised people seems to ignore the fact that every act of corruption contributes to the shaping of incentives. Specifically, the more dominant corruption is as the way of doing business in a society, the more incentive people will have to rent-seek, rather than work hard, invest or innovate.

The focus group respondents simply highlighted that corruption benefits those involved. In my opinion their sympathetic responses to the petty forms of corruption probably stems from the fact that they can relate closely to those that benefited from these corrupt acts. However I feel compelled to speak for the “silent masses” that your respondents did not relate to. These are all other people in society, who did not directly benefit from the corrupt transaction, but who are negatively affected by the perverted incentives (e.g. non-merit-based allocation of jobs, resources and votes) to which it contributed and which reduce societal productivity. Crucially, societal norms and the effects of reduced productivity tend to stick around, meaning that a sizeable portion of the silent masses are constituted by future generations of PNGeans.

Although corruption benefits those that participate in it, a micro analysis of corruption is inadequate because it is necessary to consider the overall consequences of each corrupt act, in the present and the future. I think we need to keep the message about corruption clear.

Thanks for your comment Michael, great to get your views.

First, I agree that a small-scale studies of corruption is inadequate to understand the complexities of corruption. But, given the difficulties of measuring corruption and understanding its impacts, so are all attempts to research it. The problem with most research into corruption to date is that it has relied on the perceptions of elites (see TI’s Corruption Perception’s Index, Bribe Payers’ Index, the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators, etc). Many researchers assume that we know what corruption is and it is ultimately bad for all involved, so there is no point in understanding it from a citizen’s point of view. As a result, there is a paucity of research into what ‘corruption’ means for poor people. So while small-scale research might be inadequate to capture the totality of a broad concept like corruption, right now it is absolutely necessary. Without this analysis we will continue to come to the problem informed only/mostly by elite views.

Moreover, understanding the views of the poor and marginalised should be a key concern for all of us engaged in the practice/study of development. For too long development has overlooked the views of those it is ostensibly meant to help – much to the detriment of people in developing countries.

The problem with your assumption that the ‘silent masses’ would think in a particular way is that, given the support for some of the types of practices described in the study across PNG, it is likely that we would find similar results elsewhere. (Although possibly less so with urbanites, who make up a minority of the PNG population). I’m also aware that future generations are likely to suffer from today’s corruption, as are many Papua New Guineans judging by the household survey we conducted. But future generations are also likely to be subject to the same pressures of today’s Papua New Guineans, making it doubly important to understand how poverty and culture influence people’s support/rejection of corruption. Having said this, it is very difficult to speak for future generations; it’s a group whose views are impossible to survey (I’m ruling out time travel). We’ve only got people alive today to participate in our research.

Second, the sympathetic respondents (who, it should be noted were a minority) did more than showing us that those who engage in corruption benefit from it. They highlight why corruption can be justified, and the difficulties that anti-corruption agencies face in changing these views. Anti-corruption efforts often focus the blame for corruption on those involved in corrupt acts. This sounds right, but it might be inadequate for garnering popular support against corruption. It also overlooks the structural violence of the state (and, it might be argued, other actors), through failing to provide essential services to the poor and marginalised. Given this, providing a link between acting ‘ethically’ and tangible development might help create better conditions for people to reject corruption. I’m not guaranteeing this will work, but I think it’s an option worth considering/testing. The relevance of such options, I think, only become apparent when garnering the views of local people and believing what they say.

Of course, no one wants to encourage ‘corruption’, but we must be mindful about how it is defined across time and space. As James Scott (1972) points out many acts that the west now decries as corrupt were a part of conquering colonial regimes of the past. Likewise, the rules around developers supporting political parties has changed in the past few years in NSW. Was this type of transfer always corrupt, or only when it was legislated against due to public pressure? I think we need to be mindful of these issues if corruption is to be meaningfully addressed with the support of citizenry.

Thanks again,

Grant