On 24 April, Manasseh Sogavare was declared Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister. This prompted first protest, and then riots and looting. Why?

The riots were largely an inchoate expression of anger – people empowered by the fact they had numbers on their side. The looting was opportunistic – people taking advantage of a breakdown of law and order. But what about the protests themselves? The first spark. Why were people angry? Why were they protesting?

This footage of the initial protest at parliament is illuminating. In between imploring people not to throw stones, one of the protesters, a spokesperson of sorts, angrily contrasts the protesters’ economic situation with that of the newly-elected politicians before saying in Pijin, “Sogavare step down. That’s all we need. We want a new one [Prime Minister]”. The protesters’ problem with Sogavare wasn’t necessarily personal; he was a popular politician once, but in 2019 he was returning for his fourth stint as prime minister. To the protesters he was an embodiment of the status quo. The footage ends with the protesters chanting in English, “We need change. We need change!”.

There’s no justifying violence, vandalism, and looting. But those first protesters had a point. They do need change.

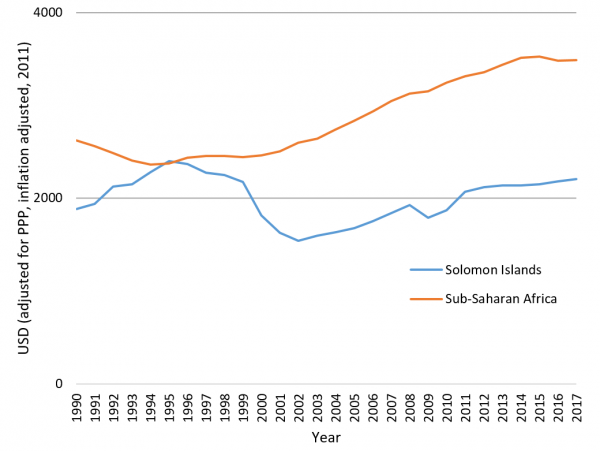

This chart shows GDP per capita over time in Solomon Islands, with the mean for Sub-Saharan African countries included for comparison. Data are from the World Development Indicators.

GDP per capita over time

GDP per capita has increased in Solomon Islands since the height of the Tensions, but the increase has been slow in recent years, and GDP per capita hasn’t yet returned to where it was in the 1990s. GDP per capita is a flawed measure of human well-being. But it’s sufficient for purpose here. Change for most people in Solomon Islands would include improved economic livelihoods. An effectively stagnant economy won’t provide them.

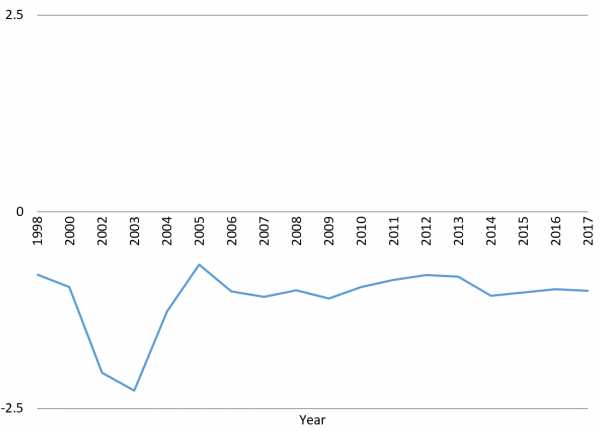

This next chart shows the World Bank’s measure of government effectiveness for Solomon Islands. The World Bank has other governance measures and, to be fair, Solomon Islands has improved on some of those measures. (All data are here.) But government effectiveness is the most relevant measure for trying to explain the protests – it captures what the government is directly capable of doing to assist its citizens on a regular basis.

Government effectiveness over time

As the chart shows, government effectiveness is not improving.

With an economy in the doldrums and a government capable of doing little to help its people, there’s an appetite for change in Solomon Islands. Particularly amongst those at the bottom of the heap. It’s hardly a surprise.

What does this mean for aid? Stagnation leading to protest and riots doesn’t sound good. Aid agencies aspire to be change agents, after all.

To give aid workers their due, some aid has helped Solomon Islands. As I said, aspects of the country’s governance have improved, and aid, alongside some Solomon Islands civil servants and parts of civil society, deserves credit for this. Aid has assisted in other areas too: electoral quality, Malaria reduction and policing are examples. Aid is helping. Aid can’t do everything. Even so, it’s hard not to see the frustration of those protesters and look at charts showing stagnation, and wonder: couldn’t aid do more?

The Australian government is clearly asking itself this question. I estimate, based on OECD Creditor Reporting System data, that between 2003 and 2014 about 75% of Australian bilateral aid to Solomon Islands was spent on governance. In this financial year, according to the latest Orange Book, just 28% will be spent on governance. (It’s possible that this one year figure may overstate the change; regardless, a major shift is afoot.) While some governance aid helped in the past, and while some needs to be continued, it is reasonable to shift aid’s focus and try something new.

The problem is that the government has lurched away from governance and towards infrastructure. An undue focus on infrastructure would be a mistake. Even setting aside donor motives, large infrastructure projects are difficult in poorly governed countries like Solomon Islands. There is a better approach.

A better alternative would be for donors working in Solomon Islands to admit there’s a lot to learn – and then to bring learning and flexibility to the fore in their work. In practice this would involve:

No fixed preference for any particular sector. If it works, aid can meet many needs: economic development, governance, human development, and more. But aid needs to work to do this. Donors should let need and efficacy drive their focus, not their own preferences for particular types of work.

Flexibility also needs to be coupled with learning. In challenging contexts like Solomon Islands, donors need to up their investment in gold standard evaluations – endeavours which aren’t subjective, or afterthoughts, but which bring the knowledge needed to decide, on the basis of effectiveness, whether work should be continued, abandoned, scaled-up, or modified.

Learning also requires donors to build their own country expertise by employing more staff who know the country well and to build systems for retaining the lessons of previous work.

In addition, learning requires employing more staff, full stop. This will increase costs, but it will also afford staff the time to learn, build relationships and make decisions in countries where giving aid well is hard.

In countries like Solomon Islands, donors should also use other development tools alongside aid, such as promoting and facilitating greater labour mobility.

What I’m suggesting isn’t radical; it would fit with approaches like Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation. Nor is it associated with any particular political ideology. It’s practical, that’s all.

Some aid already helps Solomon Islands. Some aid will continue to help. But our approach to aid giving needs to evolve if aid is to contribute to the one thing Solomon Islands needs most: change.

Terence – thanks for an interesting piece. The heavy emphasis on governance spending by Australia between 2003 and 2014 presumably reflects the costs of the RAMSI commitment (particularly but not only on the policing side). With the wind down and then conclusion of RAMSI in 2017 we should not be surprised to see a fall off in spending under the broad heading of governance since then, and a return to a more balanced portfolio.

Thanks James,

Great comment. I don’t doubt you’re right, the lion’s share of the RAMSI spend would have fallen under the category of governance.

(As an aside: I was curious how much of that went to policing, and wanted to give you a more data intensive response here, but I’ve just wasted an hour on the OCED’s CRS website trying to workout how much of the RAMSI spend went on policing, before giving up in frustration.)

The end of RAMSI, however, didn’t have to necessitate a fall in governance spending. Much of the work started under RAMSI in a range of sectors was handed over to the bilateral aid program. There’s clearly a need for better governance in Solomons. A governance focus, albeit with less emphasis on security, could still be at the centre of Australian aid work in Solomons. Indeed, in 2017 governance was still the largest sector by a clear margin (see link below). This will no longer be the case.

I don’t think that’s a bad thing per se, but I do think the best approach moving forwards would be driven by a combination of need, what other donors are doing, and likelihood of success.

My guess is that we’re probably not in disagreement on that?

And my end I’m very happy to acknowledge the importance of RAMSI’s impact on sectoral spending.

Thanks again.

Terence

Those interested Australian spending by sector in Solomon Islands over time can see the chart here:

https://twitter.com/terencewoodnz/status/1135319281032355840/photo/1

which is based on OECD CRS data.

One comment as a postscript to this. I was intending to write solely about aid, but at a colleague’s suggestion I included a line on labour mobility, which is important. However, thinking about it now, if I was going to include policy options other than those directly associated with aid I should have also included climate change, obviously. This is crucial for the Pacific — not just sea level rise but also broader changes in weather patterns.

Any donor country government that is failing to take serious action on climate change is failing the people of the Pacific. Climate change will be change, but of the worst possible sort.