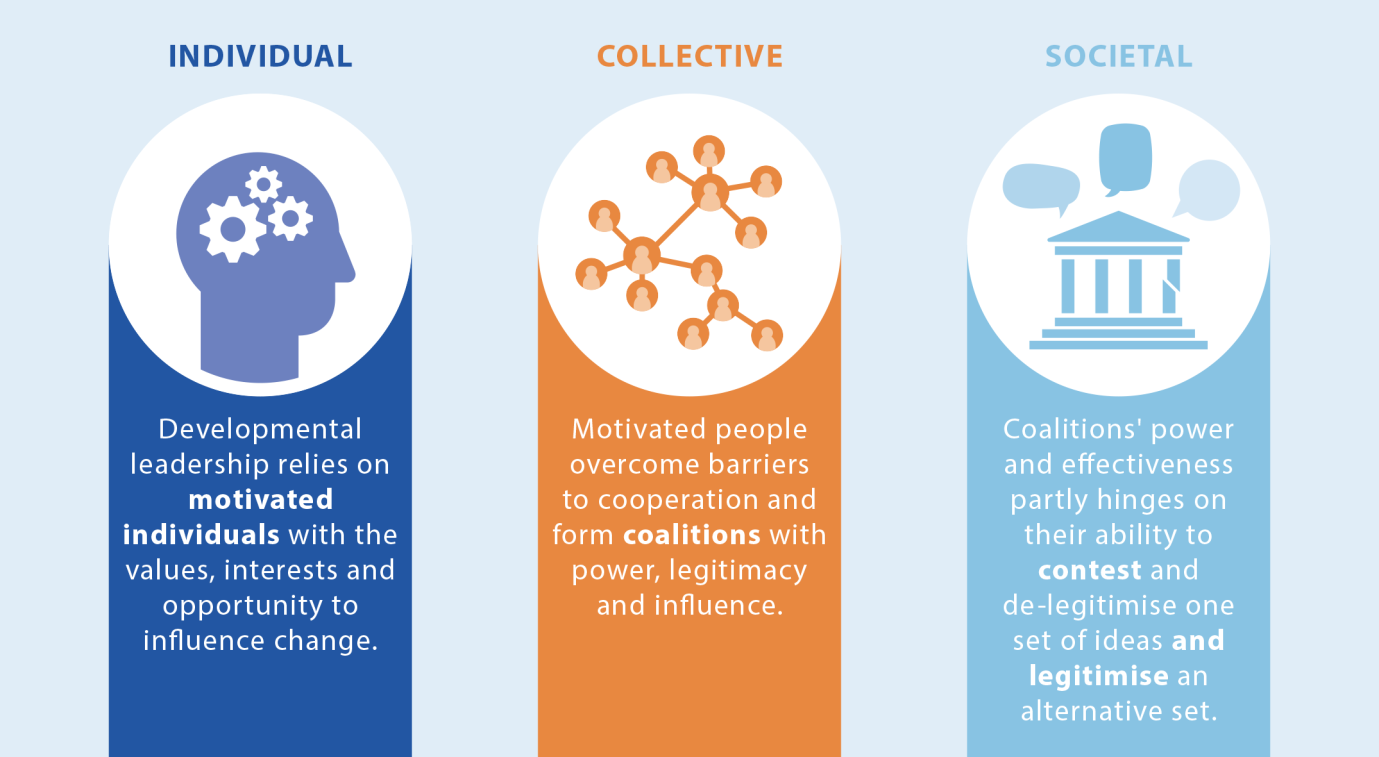

Elements of positive development outcomes (Credit: Developmental Leadership Program, 2018)

The fate of leadership which aspires to leave no-one behind

By Chris Roche

31 May 2019

Australia’s new government faces a range of challenges, including – along with 192 nations – how to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As a number of observers have noted, this will require sustained and creative leadership. But what kind of leadership does the country, and the region, need if we are to address the challenges we face? What kind of leadership is required if, in the words of the SDGs, we are to ‘leave no-one behind’? How do different groups understand and experience different forms of leadership? And critically, what kind of leadership do citizens seem to want?

Arguably, one place we might start to look for answers to these questions is from other countries who are also seeking to achieve the SDGs, given their universal aspiration and the fact they seek to address social, economic and environmental concerns simultaneously. As David Lewis has previously suggested, ‘South-North’ learning in this regard has been largely undervalued.

For example, recent publications by the Developmental Leadership Program (DLP) have synthesised ten years of research on these questions, and have explored the relationship between gender, leadership and politics. This work suggests that leadership which is developmental, i.e. that which contributes to positive development outcomes, tends to rely on three elements:

- First, it relies on motivated and strategic individuals with the incentives, values, interests and opportunity to push for change. These characteristics are often shaped by secondary and tertiary education.

- Second, these motivated people must overcome barriers to cooperation and form coalitions with sufficient power, legitimacy and influence.

- Third, coalitions’ power and effectiveness partly hinges on their ability to contest and de-legitimise one set of ideas and legitimise an alternative set. In already divided societies, whether services support or undermine state legitimacy can hinge on competing perceptions of fairness.

These findings would suggest that the individual leadership of single political parties will be insufficient in the absence of the collective leadership of broader cross-sector coalitions which bring public sector, private sector and non-governmental actors together. Arguably there does not yet seem to be a large or powerful enough coalition to shape societal perspectives on issues such as inequality, international cooperation or the climate crisis – indeed such concerns are still seen or portrayed to be either irrelevant to their lives or indeed ‘post-material’.

Secondly, it suggests that we have not yet found successful means by which these issues can be properly and inclusively debated and contested. Filter bubbles, shrill polarised arguments and personalised attacks seem to characterise public discourse at the expense of more measured dialogue and debate. DLP’s research suggests that it is perhaps the absence of venues and spaces which are conducive to exchanges of this type that explains why these concerns are not yet seen to be legitimate enough to command the support of a majority of the electorate.

Thirdly, it is clear that societal and gender norms shape perceptions and practices of leadership in all countries. As Julia Gillard noted on her ousting as Prime Minister “gender doesn’t explain everything about my prime ministership, it doesn’t explain nothing; it explains some things. And it is for the nation to think in a sophisticated way about these shades of grey.” If ‘no-one is to be left behind’ in Australia then there is clearly a discussion to be had about the forces that seem to be reinforcing divisive rather than inclusive forms of politics and leadership. There is much to be learnt from the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, which is comparing and contrasting the experience of women’s leadership in different countries.

All of which may mean that if Australia is really interested in achieving the SDGs and leaving no-one behind it might learn a lot from the experiences of developmental leadership elsewhere. Fortunately, these issues and more will be discussed at the RDI 2019 conference on leadership for inclusive development on 12-13 June at La Trobe University in Melbourne. If you want to hear a great range of speakers from around the world talk about these issues, including Fiame Naomi Mata’ afa, Deputy Prime Minister of Samoa; Dan Honig, author of Navigating by judgement: why and when top down management of foreign aid doesn’t work; and Srilatha Batliwala, Senior Advisor, Knowledge Building and Feminist Leadership with CREA (Creating Resources for Empowerment in Action), register here.

About the author/s

Chris Roche

Chris Roche is Director of the Institute for Human Security and Social Change, and Associate Professor at La Trobe University and a Senior Research Partner of the Developmental Leadership Program. Chris has worked for International NGOs for nearly 30 years, and has a particular interest in understanding the practice of social change and how it might be best catalysed and supported.