Women’s economic empowerment: the importance of small market stall vendors in urban Papua New Guinea

By Nayahamui Michelle Rooney

16 June 2016

Women’s economic empowerment is a key priority in the development agenda in Papua New Guinea, and is viewed as a key solution to empowering women and addressing problems like poverty and gender-based violence. To address this, significant attention is being given to employment creation, to women’s engagement in the agricultural sector or improving urban market places. In urban areas significant efforts, with considerable donor support, have been made towards improving the state of urban market places so they are safer and more accessible to women.

Less attention has been paid to the many women in urban areas who make their living from the smaller market stalls that are so prevalent in places like Port Moresby.

Rather than viewing these smaller local markets and home-based stalls as marginal players in the bid to improve women’s economic empowerment, small market stalls are just as – if not more – important than the larger markets because they are such a prolific feature of the urban landscape. Understanding these small stalls as sites of economic empowerment can shed important insights into local processes of women’s empowerment and disempowerment, and the moral values and norms that shape how women make a living.

Small market stalls play an important social role in the localities. They are places where people convene to catch up with the day’s news, organise plans to support each other with issues like childcare, or simply to take a breather and have a conversation. Community communication takes place at these sites not only through leaving messages for each other but through the sales of phone credits or sharing of news. Other important economic activities also occur, such as the borrowing and lending of cash by the vendor to a known customer who has fallen short of money to buy food or other items. Because many of these stalls operate into the night, they can also have implications for improving law and order in urban areas. As lit-up areas where people interact, they often provide a sense of security in localities which enables more people to move about in the evenings – something places like Port Moresby desperately need.

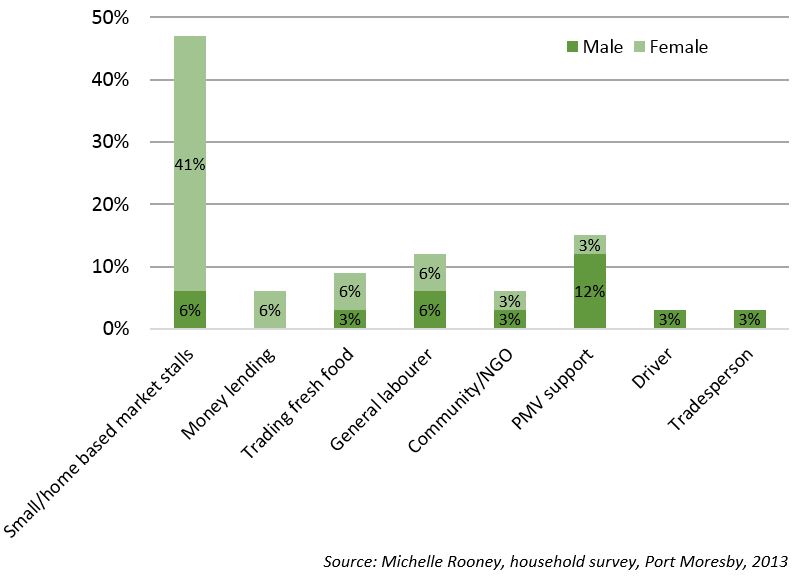

Evidence already tells us that a significant number of people in urban areas rely on the informal sector, and that women dominate this form of economic engagement [1]. A similar pattern is shown in the findings of a small survey I conducted during my fieldwork in Port Moresby in 2013. Men dominated income earning activities in waged employment while women were the key players in the informal sector (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Types of income earning activity, by gender (%; n=82)

Moreover, among those that were engaged in the informal sector, by far most people were operating small market stalls near their homes, which I refer to as ‘residential markets’ in an earlier paper [pdf] (Figure 2). Of those operating small market stalls, the majority were women who were mothers. Most had a husband who was employed in the formal sector.

Figure 2: Types of informal sector activity, by gender (%; n=34)

Although these figures are for a survey conducted in a settlement in 2013, it is worth exploring if this pattern is the same more broadly across Port Moresby and other urban areas in PNG.

Most of the women running home-based or roadside market stalls are mothers with young children, elderly or ill. Even if they are more able and willing to be more economically engaged, many lack access to land in the surrounding region to make gardens. Many are also not in a position to engage in the wholesale purchase of goods from rural gardeners to engage in the larger urban markets.

Perhaps most importantly, as this report highlights, we need to recognise that women’s economic engagement does not take place in a vacuum, void of family, social and cultural dynamics. Most of the households that I interviewed deployed an income generation strategy that combined different forms of income. Mainly, the husband was employed in wage employment while the wife ran a small market stall. Other members of the household may also be engaged in some form of income earning activities. Indeed, households that combined formal wage and informal incomes also had the highest incomes. In this role, women are vulnerable in the sense of having a low income which is subject to being appropriated by other family members, but they are also a powerful force in enabling their families to survive the fortnightly cycle of wage income. Without access to gardens, urban livelihoods depend on cash incomes, and urban household dynamics involve a negotiation between those in the formal and informal sectors that is critically important to enabling the household to survive. While formal incomes, generally paid on a fortnightly basis, provide a stable and predictable income, it usually falls short of sustaining the family’s entire needs over the fortnight. When the family falls short they turn to the informal income earner – usually the mother whose income is earned on a daily basis from her small market stall – to supplement income until the next payday. Because the income is earned daily, the family is able to buy food in smaller portions on a daily basis.

For many — perhaps most — women in urban areas, small market stalls are usually their most viable option for making a bit of money to support their families. These intimate spaces of economic and social empowerment have been long neglected, but deserve to be better understood.

Michelle Rooney is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. She is supported by funding from the Australian Aid Program under the Pacific Leadership and Governance Precinct, through the ANU-UPNG Partnership.

[1] Gibson, J. 2013. Technical Report: The Labour Market in Papua New Guinea (with a Focus on the National Capital District). Waikato: University of Waikato.

About the author/s

Nayahamui Michelle Rooney

Nayahamui Michelle Rooney is a lecturer in the School of Culture, History and Language in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.