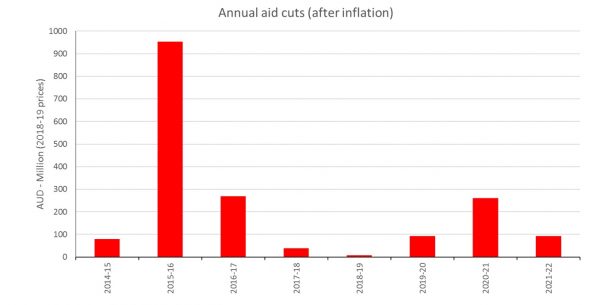

This year’s budget sees a small increase in foreign aid in 2018-19 almost in line with inflation. There is also a modest boost to aid this and the following year to fund our capital subscription to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. That’s the good news. The bad news is that there is no increase at all after this year out to 2021-22 to offset inflation. If these forward estimates come to pass, aid will have been cut in real terms for a record eight years in a row – by a government that was elected to office in 2013 on a promise to increase aid in line with inflation. The funding freeze for foreign aid which previously ran to 2020-21 has been extended by one year in this year’s budget compared to last. So accustomed is it to cutting aid, the government didn’t even both to give a reason for the freeze extension this time.

Following rumours that the aid budget was in the firing line for savings once again, many readers will be breathing a sigh of relief that there were no immediate cuts. It could have been worse. After all, the Abbott-Turnbull governments have already overseen the largest ever reductions in Australian aid.

Nevertheless, this budget is a disappointing one for aid. The fiscal and broader economic context in which the budget has been delivered is the most positive since the Coalition took power. Robust growth has boosted government revenue, enabling the government to both increase spending and cut income tax without significantly damaging the budget bottom line. Indeed, the underlying budget deficit in 2018-19 will be the lowest since the Great Financial Crisis. By 2019-20, the budget is projected to move into surplus. If aid was cut because of deficit and debt problems, why is it cut further when these problems are receding?

The aid cuts are not the result of austerity. Government spending increases 16.8 per cent over the forward estimates, and will be 46.3 per cent higher in 2021-22 than it was when the Coalition came into power (when measured in nominal terms). Foreign aid will have fallen 17.6 per cent (in nominal terms) over the same period, a decline of 32 percent when adjusted so as to account for inflation.

These reductions have taken place in a period of affluence. Australia has entered its 27th consecutive year of economic growth. As a result, aid as a percentage of Gross National Income – a measure of generosity used across the world – has already fallen to a record low of 0.23% and will continue to fall to 0.19% by 2021-22, which will put Australia about equal with crisis-hit Spain. Interestingly, tonight’s budget comes at the same time as New Zealand announces large aid increases.

If there is a silver lining in this year’s foreign aid budget, it is the Pacific.

The undersea telecommunications cable to PNG and to, and within, Solomon Islands had already been announced by the government, following its decision not to allow Huawei to connect its proposed cable to Australia on account of security concerns. It was expected that funding for this initiative would come at the expense of other aid commitments in these countries. That will not be the case. Instead, the cost of these initiatives will be borne in part by real reductions elsewhere in the aid program, as well as nominal cuts to Indonesia and Cambodia (the latter having failed to resettle more than a handful of asylum seekers attempting to enter Australia).

There is also new funding for regional activities in the Pacific, including the Australia-Pacific Security College, and support for labour mobility through the Pacific Labour Facility – an acknowledgement of both the real economic benefits of labour mobility for the Pacific, and of the role that aid can play in support of such mobility.

Australia has also announced it will open a high commission in Tuvalu (the first for that tiny nation, unless one includes Taiwan’s embassy).

So, a good budget for the Pacific but another gloomy one for foreign aid as a whole. What will it take for this government to stop cutting aid?

Here it’s only the rumors that the aid budget is low. I think Helen Hughes has a different view on increasing the budget of aid in the Pacific islands. She had a bad impact on the Pacific. The Australian government is giving no sign on the labor. I have much more to say but will conclude my comment they are improving the quality submission to aid.

Why does AU continue to ignore that a Vanuatu private sector-led initiative is already building a cable to SI without aid support? VU has awarded the cable supply contract to a USA supplier (not China). The enormous AU cable grant to SI and PNG is distorting the market.

The former Director of Development Studies, the late Helen Hughes had a different view about increasing aid in the Pacific islands. She said that aid is bad for the Pacific. A Harvard economist Dambisa Moyo also shared similar views in terms of giving aid to Africa. Aid in PICs needs new thinking and approach. Where do we capture the voices/views of those carrying the burden and the problem? Do they also participate (and or trained to meaningfully contribute) in needs assessment and consultations.

Thanks for this comment. Moyo’s book is very weak, and I don’t think she can be described as an economist. But Helen Hughes had a point. Whether or not aid is bad for the Pacific, it doesn’t seem to be that good. New approaches are needed, which is why it is so good that the Australian government is now giving much more emphasis to labour mobility, including starting to use the aid program to promote labour mobility. A lot more could should be said in response to your important comment, but I’ll conclude for now by saying that we welcome all quality submissions related to aid – positive or negative – and especially from those in recipient countries.

Why does AU contunue to ignore that a Vanuatu private sector led initiative is already building a cable to SI without aid support? VU has awarded the cable supply contract to a USA supplier (not China). The enormous AU cable grant to SI and PNG is distorting the market.

To add to Peter’s aid ‘success’ examples, microfinance has over more than 3 decades, developed into a widely used method for moving people out of poverty.

By making small collateral free loans available to even the poorest people, families are given a dignified self-employment opportunity. It has been shown over the years that microfinance clients – mostly women – improve their living standards, educate their children and become respected members of their community.

With persistent encouragement by NGOs, Australian aid has supported microfinance programs. I wonder if it still does?

Can I suggest a somewhat different slant to that question, which I do suggest should alternatively read: “when will the Australian public believe in the merits of Australia’s aid” ?

The big picture surely is the excuse given by the very Minister in charge of the aid budget – no increase, because the Australian people don’t believe in it. Thus abrogating her role to argue in favour of her responsibilities.

There does seem somewhat of a disconnect between the people who believe in aid and those who decide the aid budget, with the unbelievers seemingly in between. Result is – the aid budget keeps being cut, despite the appropriateness of your original question.

There is rarely good news about successes in the outcomes from our aid budget – either from the Foreign Minister or her junior. Much less from the NGOs actually in the field spending money from Australia’s aid budget.

And by “good news”, I mean publicly – in the media and other places where the voter can be informed. Not quietly circulating in NGO offices or DFAT cabinets.

I once helped fund an AusAID program in Afghanistan – training women to be paralegals and act as defence counsel in domestic violence cases. I appreciate the security situation affecting civilians in that country, but that is just one example of what I would call success.

At the time of the World Summit for Children in 1990, 40,000 children were dying each day from preventable causes. In 2016, UNICEF estimated that figure to be 15,000 https://www.unicef.org.au/about-us/media/october-2017/7-000-newborns-die-every-day-worldwide-despite-st

Still preventable, but that does represent progress and results, by aid donors and aid recipients – over a long time.

That’s what’s lacking in your comments above – bringing about changes for the better among the people of our world.