The atoll of states of Kiribati and Tuvalu have the unenviable distinction of being among the countries in the world that are most vulnerable to climate change. Both atoll nations are situated just metres above water. Both are already feeling the effects of a changing climate, with recent years seeing king tides affect the urban atolls of South Tarawa and Funafuti, and cyclonic activity causing extensive damage in Tuvalu.

Together with Nauru, these countries also have another unenviable trait: their citizens are afforded few opportunities to migrate overseas to live and work.

Nauru (population approx. 11,000) is the only Pacific island state with a population of fewer than 100,000 people that has no special migration access to a larger country. Kiribati and Tuvalu have very limited access to New Zealand, with 75 places available each year for applicants selected by ballot. This minimal level of migration access sets these countries apart from other similar small nations in the Pacific, whose citizens are able to freely migrate to wealthy larger countries with which they have a special relationship (New Zealand, in the case of Niue and Cook Islands; and the US, in the case of Palau, Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia).

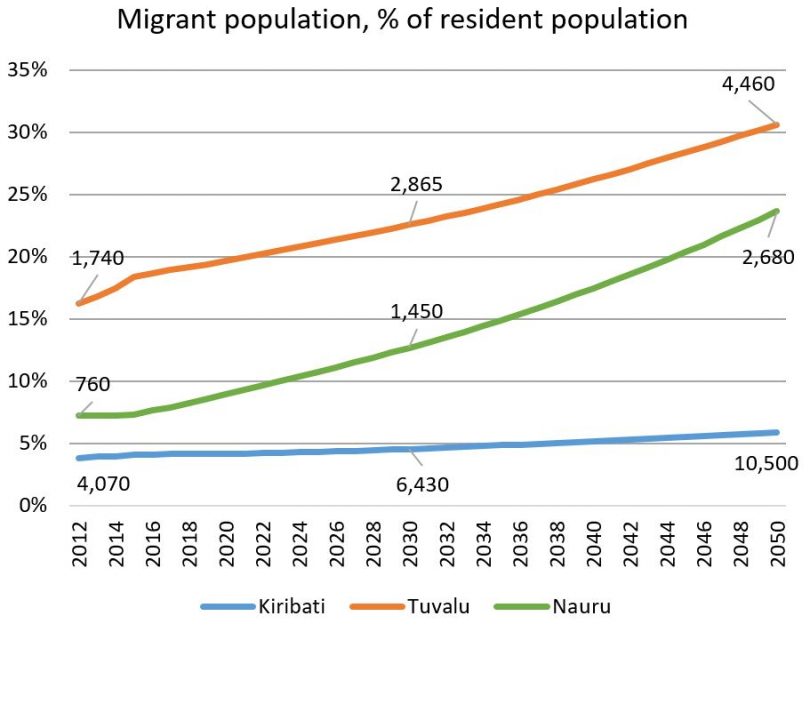

Kiribati (population 118,000), unlike Tonga (population 108,000), has low levels of emigration and a very small diaspora resident in Australia and New Zealand. The migrant population in Kiribati numbers less than 5,000, or about four per cent of the resident population. In the case of Nauru and Tuvalu, this percentage is about eight and 19 per cent respectively. The diaspora of all three countries, but especially Kiribati and Nauru, is modest when compared to those of other small island states like Tonga (approx. 50 per cent), Samoa (46 per cent), FSM (34 per cent), Marshall Islands (27 per cent) or Palau (31 per cent), Niue (81 per cent), and Cook Islands (63 per cent).

Citizens of these countries have struggled historically to access skilled migration opportunities. An IT worker from, say, Bangalore, can use Australia’s skilled migration pathways in a way that a prospective migrant from Kiribati simply cannot do (there would be few I-Kiribati with the necessary qualifications, and a tiny private sector in Kiribati makes it difficult to gain relevant experience).

The reason this is important for climate change adaptation is that migration opportunities can form an important household strategy for coping with the harmful livelihood effects of environmental changes. Indeed, as the effects of climate change become more burdensome, other adaptation strategies will become less effective, making access to migration opportunities more important.

In a recently released report, we examine migration opportunities and project future migration from Kiribati, Tuvalu and Nauru through to 2050, examining fiscal and economic impacts.

Climate change is not the only factor influencing migration from these three island states, of course. Small island developing states have long faced a number of challenges to their survival.

Growing population density is especially problematic for the atoll states, given the limited amount of arable land that is available and the ongoing reliance on subsistence agriculture and fisheries (less an issue in Nauru). One CSIRO study has suggested that the human carrying capacity of small islands is approximately 100 people per km2 (Foale 2005, Butler et al. 2014b). UN population density estimates show that in 2015, Nauru and Tuvalu had 563 and 367 persons per km2 respectively, while Kiribati (excluding Kiritimati Island) had a population of 251 persons per km2. These figures are increasing in Tuvalu and Kiribati, and rapidly so in the case of Kiribati.

Migration, both internal and overseas, has historically been a key adaptive strategy for some households in these countries (for example, Tuvalu and Kiribati for decades sent large numbers of seafarers overseas to work on container ships). But in today’s bordered world, opportunities for migration overseas are limited for those without the requisite qualifications. The migration opportunities that do exist are least available to those who live in the most vulnerable locations and circumstances.

We argue in our report that for migration to perform its role as an adaptive strategy (one of several), more migration opportunities need to be provided to low-income households. Freely chosen, managed migration of a population is more effective than large-scale, reactive migration in response to a humanitarian crisis.

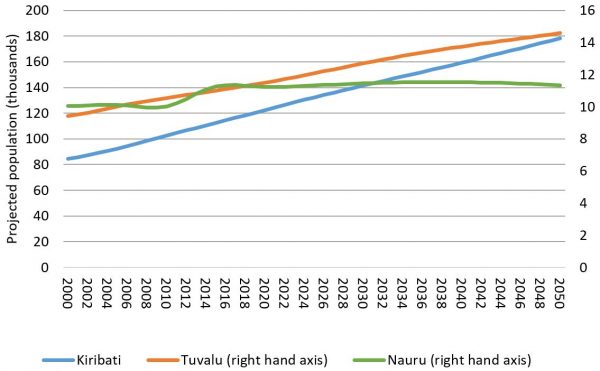

Present trends are especially concerning in the case of Kiribati, given a growing population and limited availability of arable land. By 2050, the UN projects that Kiribati’s population will have risen to 180,000 (that of Tuvalu and Nauru will be 14,000 and 11,000 respectively). Kiribati’ diaspora resident overseas, when measured as a proportion of the Kiribati population, will barely grow at all.

Figure 1: Projected population, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Nauru

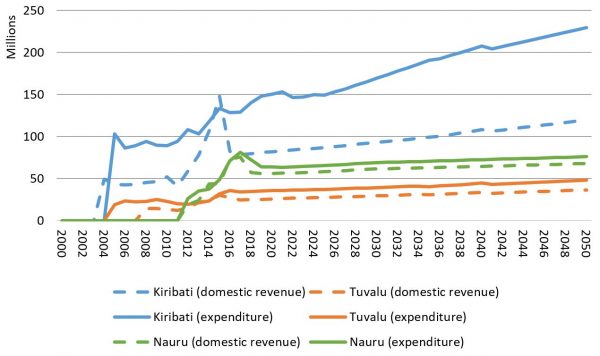

Though formal sector employment and the number of I-Kiribati with a post-school qualification will rise, the increase will not be commensurate with growth of the working age population. As a result, expenditure on health and education will rise relative to domestic government revenue (which is linked to formal employment). This in turn will contribute to a growing fiscal gap (caused by a mismatch between government expenditure and revenue) that must be met through aid funding or reduced services. A similar – though less extreme – picture is also evident in Tuvalu and Nauru (see Figure 2), with developments in the latter strongly influenced by the future of the offshore processing centre.

Figure 2: Government revenue and expenditure

Migration can form an important adaptive strategy for households in over-populated areas, including areas affected by climate change. Yet historically, we know that migration from Kiribati, Nauru and (less so) Tuvalu has been limited. The major constraint? Limited opportunities are available for low-skilled workers to migrate for the medium to long term to Australia and New Zealand.

If we are serious about adaptation in atoll contexts, migration should form part of the discussion. The challenge is to work out ways that managed migration pathways can be fostered for more vulnerable households: pathways that benefit low-skilled workers, and which are accessible to those who want to migrate but lack the resources to do so. Such pathways, combined with a larger diaspora residing overseas, will help those who are prepared to migrate. As well, such migration pathways will benefit those who want to stay through the development of a safety net and more general support for those with family overseas.

In Australia, the establishment of temporary labour mobility schemes and the re-design of the Australia Pacific Training Coalition signal steps in the right direction. But more is needed. Linkages between different schemes should be strengthened and made more explicit. Special permanent migration pathways for these countries to Australia are needed, like the type, albeit on a larger scale, that have existed for years to New Zealand for citizens of Pacific island countries through the Pacific Access Category and Samoan Quota visas.

Read the full report here.

One of the main factors preventing Tuvaluans from using the PAC visa is the cost- of the various medical and X-ray examinations, the entry fee for the ballot ($150 for the first try, and $50 thereafter), and the cost of travel from Tuvalu to NZ to secure a firm job offer. This means that only the fairly affluent Tuvaluans can afford to migrate, and with their better (presumably?) education levels, these might be the very people that Tuvalu needs to keep to help in future development? At the very least, NZ could abolish the entry fee for the ballot?

The authors provide figures for projected OUT-migration from these three central island states as they link Them to outsiders’ concerns about Climate Change.

But whose concerns are they citing? Are ‘opportunities for skilled migrants’ the concern of these populations?

Surely the figures/graphs indicate the answer. Home is best.

Have the authors considered the historical background to the Tables of percentages of the populations’ out migrations.

the early histories of these three nations indicate a strong adherence to their lands in the face of outsider interests.

In the case of Nauru during the 20th century their population has been decimated several times by forced out- Migrations, particularly 1941-1945 when one third of their population died during forced exile to Truk/Chuuk by Japanese; later Australian suggestions to relocate Nauruans on islands off Australia were soundly rejected by Hammer de Roburt and his team ( See Pollock 2016 for a History of the effects of Mining Phosphate on Nauru – The Mining Curse, JSO).

Nauruans, as well as IKiribati and Tuvaluans are strongly attached to their Lands — and, as in the case of many other Pacific Island studies, see no need to leave their Homelands. Out migration Is not an attractive proposition.

In Nauru’s case their small land area, 21 sq km., was drastically reduced by 80 percent by Australian and New Zealand phosphate mining activities during 20th century; Nauruans have been reduced to living on the small perimeter of their island. Why leave their island home? And Australia’s Pacific Solution (2002-2017) has contributed significantly to increased population density adding increasing the 9000 strong population Nauru by some 4000 Asians held in Australian Detention Camps.Sharing their Island makes Nauruans treasure their island even more highly. No emigrant skills are needed.

A study of the concerns about climate change by I Kiribati living in New Zealand will reveal reasons for that aspect of their ‘Diaspora’ (Petra Autio 2018).

Nancy

Thanks for your feedback. Unfortunately, the blog did not allow us to report all of our analysis. In particular, we cite three UN funded surveys of the attitudes of the residents of Kiribati, Nauru and Tuvalu to climate change and migration, conducted by social scientists from New Zealand. See for example Oakes, Robert, Milan, Andrea and Campbell, Jillian (2016). Kiribati: Climate Change and Migration – Relationships Between Household Vulnerability, Human Mobility and Climate Change. United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security.

These surveys found that that more than 70 per cent of households in Kiribati and Tuvalu, and 35 per cent in Nauru believe that migration would be a likely response for them if droughts, sea level rise or floods worsened. However, the same surveys show that only a quarter of households in Kiribati, Nauru, and Tuvalu believe that they will have the financial means to migrate.

We concluded from these results and other evidence such as the number of applicants for the 75 places each year for Kiribati and Tuvalu to migrate permanently to New Zealand that there is a large group who want to migrate to live and work overseas. The size of the group will depend on whether they have the resources to do so. We suggest that providing more opportunities and resources to support short, medium and long-term migration Australia or New Zealand will give more residents in these three countries the chance to choose whether to stay or go as a response to climate change.

Hi Richard and Matthew,

I really appreciate your recent study on migration as a pressure release valve – I couldn’t agree more, it is adaptation with human rights and development at the stroke of a pen. It’d be great if that would become policy, but I fear we are a long way form that right now.

Another reason why this is a good idea is because if displacement ever arises social networks in and familiarity with the places people may have to move to reduces the economic and psychosocial impacts on people who are displaced.