Coalition governments are popular feature of parliamentary democracy. Since 1972, PNG has had coalition governments. As explained in this survey, one theory is that to minimise the bargaining cost of coalitions with different policies, parties with the smallest ideological differences tend to form a coalition. Another approach is the “office-oriented” theory, whereby parties seek to form a winning coalition with the goal of securing a majority of the portfolios. This group would restrict the number of political parties in an attempt to maximize their portfolio numbers. However, if MPs from a few parties are not sufficient to form government, numerous parties can combine, with the major party in the coalition negotiating and controlling the distribution of portfolios.

In general, PNG’s political parties lack political ideology, but parties do have some policies. For this blog, I look at each party’s education policies (whether they support free or subsidized schooling) and their position on regional autonomy to see what impact, if any, policy similarities and differences had on coalition formation. These two areas were chosen because they seem to be the only ones where parties have relatively clear policy positions.

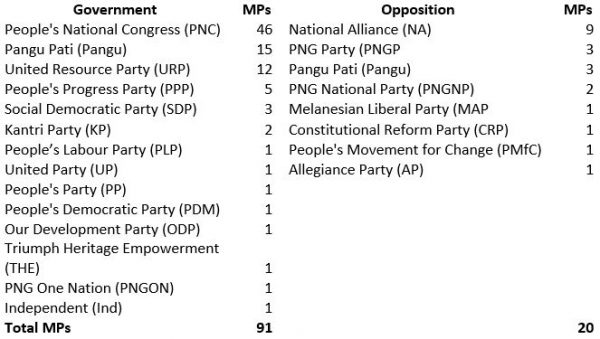

Table 1 below shows the number of parties currently in parliament, their MPs, and whether they are in government or the opposition. The People’s National Congress (PNC) dominates the government coalition with 46 out of 91 MPs, whilst the National Alliance (NA) leads the opposition with 9 out of 20 MPs. Pangu has MPs in both the government (15) and opposition (3).

Table 1: Political parties and MPs as of July 25 2018

Source: Brian Kramer, Facebook (13th July 2018); Loop PNG (17th July 2018).

Education policy

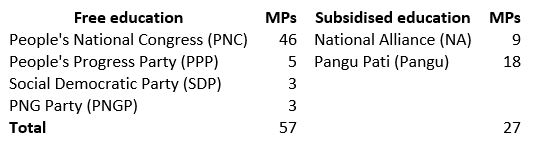

Based on analysis of their speeches and other material in the run up to the 2017 elections, four political parties – PNC, PPP, SDP and PNGP – support no tuition (school) fees, and two parties – Pangu and NA – advocate for subsidised tuition fees (Table 2). The other parties do not have a clear position on whether there should be tuition fees or not.

Table 2: Parties supporting free or subsidised education

Source: Author’s own from NRI seminar (April 2017), newspapers, and IPPCC website.

A coalition based on free education would have had PNC, PPP, SDP, and PNGP with 57 MPs on one side, and NA and Pangu on the other side with 27 MPs. Currently, as shown in Table 1, NA is in the opposition with only two Pangu MPs and PNGP, whilst the rest of the Pangu MPs are out of place in the government coalition with PNC, PPP, and SDP.

Autonomy

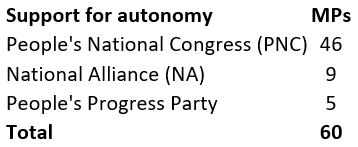

A coalition based on policies supporting regional autonomy would have had PNC, NA and PPP on the same side. PPP has advocated for autonomy as a policy since 2008. Leading up to the 2017 elections, Peter O’Neil stated that New Ireland East and East New Britain would be granted autonomy, and the Bougainville referendum would go ahead in 2019. This was captured in Alotau Accord II, a coalition agreement. It became a key element in attracting PPP to the coalition. Following the seminar on the Bougainville Referendum hosted by the National Research Institute (NRI) in June 2018, East Sepik Governor Allan Bird from the National Alliance party talked about his desire for Greater Sepik Autonomy on Facebook. The other parties do not have a clear position on autonomy. Table 3 shows what a coalition would look like if based on pro-autonomy policies. However, as Table 1 shows, NA is in fact in the opposition.

Table 3: Ideal coalition partners based on policies supporting autonomy

Source: Author’s own from NRI seminar (April 2017), newspapers, and IPPCC website.

Conclusion

On education, Pangu’s policies are incompatible with the government coalition (PNC, PP and SDP), and yet it joined the government. PNGP is content to remain with the opposition despite having similar policies on education as PNC, PPP and SDP. PNC, SDP and PPP have a similar free education policy. However, senior PPP MPs (Ben Micah and Julias Chan) joined the opposition in an attempt to oust Peter O’Neil (PNC) as Prime Minister in 2016. The role of education policy in determining a coalition is therefore not clear. On autonomy, the only clear case is PPP’s decision to join the coalition, which was largely based on Peter O’Neil’s (PNC) promise of autonomy.

This analysis confirms that what best explains the decisions of political parties in PNG is not policy or ideology but the interest of MPs in attaining Cabinet portfolios and gaining access to financial resources (DSIP/PSIP). There are 31 ministries, 12 vice-ministries, and 31 permanent committee chairmen positions that the government distributes. The major party in the coalition, PNC, acts as the centripetal force, distributing these portfolios. PNC holds 20 of the 31 portfolios, URP has four, PPP three, Pangu two and SDP and UP have one each. The portfolios are roughly proportional to the number of MPs each party has except Pangu, which has two portfolios despite having the second largest MPs in the coalition. This is because Pangu joined the coalition late.

The opposition awaits the end of the grace period in order to to replace the government coalition via a vote of no confidence. Based on this analysis, their interest is in government portfolios rather than government policies.

Since this post was published, an error in Table 3 has been corrected to reflect the actual number of MPs in the National Alliance (NA) who support autonomy – nine.

It’s a good post that all PNG politicians are working together, but it seems that no change in our country. How will our country change, that’s the question.

Dear Michael Kabuni, this is an an excellent blog post.

Political parties as a institution have only begun to form political positions on some issues affecting Papua New Guinea in a broad range of area’s. However, the maturity continuum of PNG political parties and their party policies have only began to discover the importance of party policies platforms only insofar as it attracts membership to their party, relatively recently.

I think part of this interest is buttressed or aided by the establishment of the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidate’s Commission.

I do agree with you to some degree that political party coalitions have largely been influenced by monosaturated politics over time since the first General Elections in 1962. It is only recently that there is a huge contradiction between Monosaturated Politics and Polysaturated Politics.

The question is : do policies matter? I think the answer to that question is best informed by how the party leader’s and political power-brokers answer this question on the floor of parliament during the formation of government. Of course the party with the biggest number of votes is invited by the Governor General to form government.

Academically , yes political party policies are important. Politically, it’s important to be in a party. In practice, it depends on political thinking at that very moment.

I think the most important question for me is: why can’t smaller parties merge with bigger parties?

Most people dont realise how important party platforms and policies are. I personally see that most policies our current political parties dwell on seems old. For instance, ‘Free education policy’, that was PDM pary platform .

However, many smaller parties do not have a clear cut on their partys platform and policies.

It is better to draw party policies and platforms according to situations and changes we are facing now and what would come after.

Very interesting blog.

How about health policy(ies)?

It looks obvious our leaders are concerned too much on power grabbing than addressing or having less consideration into public health.

Almost all parties have some form of policy towards, though it’s not stated in terms which would be easy to analyse. For instance, phrases like “improve rural health, promote healthy living, provide critical drugs, improve human resource and capacity building etc.” It’s the same with most of the policies of these parties. Generic.

This is a good paper however, sever issues with analysis. In your conclusion, you argue that what explains the decisions of political parties in PNG is not policy or ideology but the interest of MPs in attaining cabinet portfolios and gaining access to financial resources (DSIP/PSIP) and that the ruling party (PNC) distributes cabinet portfolios roughly propositional to the number of MPs in each party. This is something I also agree with however, your data and analysis has loopholes that contradicts these arguments.

1. Why didn`t the National Alliance Party join the ruling coalition despite a similar policy take on Autonomy? Clearly it would have comprised of the third largest party after United Resource Party (NA: 11 and URP: 12) and its members would have been given cabinet portfolios or why didn`t it split like Pangu, where three quarters of its members along with their leader moved to the ruling party for greater access to portfolios and finance as per your arguments?

2. Why did PNG Party members remain content with the opposition despite having a similar take on free education policy and having three members? Clearly they would have gotten at least one cabinet portfolio if all three or at least 2 crossed over. This can be justified based on your data since SDP with three members has one member with a cabinet portfolio and United Party with only one member but still managed to get a ministerial portfolio.

3. If the PNC Party acts as a centripetal force distributing portfolios roughly in proposition to the number of MPs each party has and that policy or ideology has little relevance over ministerial portfolios than why didn`t Kantri Party receive a cabinet portfolio despite having two members compared to United Party with just one member?

Cheers

Hi Francis,

Thanks for the comments and points raised. I have advanced the argument on possible reasons a to why MPs move over to the government side. I briefly stated towards the end why the other parties are content to remain in the opposition. Response to your questions:

1. Why didn’t National Alliance join PNC with it’ larger numbers and have the portfolios? NA initially hoped to form the government, that is why it did not join PNC after elections. Patrick Pruaich also fell out of favour with PNC towards the end of last parliament, and after 2017 elections, was joined by the likes of Allan Bird, who are vocal against the government.

Why didn’t they NA MPs then break away like Pangu members did? NA members did break way from NA: Richard Masere, MP for Ijivitari Open was an NA member, now he’s with PNC; Jimmy Ugoro, Usino-Bundi MP, left NA to be with PNC; John Simon, Maprik MP, left NA to be with PNC. Each of these MPs cited relative ease of accessing funds for their electorates as the reason for leaving NA and Opposition.

Why were they not given ministry portfolios? They moved to PNC at different times (Masere moved before the two). They didn’t have the numbers to negotiate as Pangu did. PNC had to remove one ministry from it’s own party to give to Sam Basil, and revived the another dormant portfolio (minister assisting the PM) to give to Basil’s deputy. Number does determine portfolios.

2. PNG Party: Again, they were at the Kokopo Camp with NA & Pangu hoping to form the government. That is why they did not join PNC initially. Also, these parties were all anti-PNC during the campaign (in fact they were anti-PNC way before the campaign started). Pangu’ movement to the government after they failed to form the government proves my point that access to funds and portfolios determines coalition. When they failed to defeat PNC, they joined PNC to access them. The others will wait for a chance to change the government. They are content to remain on the opposition. Belden Namah’s long-standing feud with O’Neil may be another reason why he remains in the Opposition.

3. Why didn’t Kantri Party have a portfolio when it had 2 MPs compared to United Party which had one MP but has a portfolio? Loyalty: United Party leader Rmnbink Pato has stuck with O’Neil since 2012, supported him in vote of no confidence in 2016, and moved to PNC-led camp as soon as he won.He is someone O’Neil can trust to support him. That is something Kantri Pati not done.

Congratulation, it’s a good blog.

I didn’t read the entire blog but, I noted the issue of MPs deflecting from embracing party policies on basic services such as health and education and pursuing DSIP/PSIP and privileges that accompany portfolios in the government camp.

Many of them claim that they moved in the best interest of their people but fail to deliver during their term. The data presented says it all. Keep publishing and exposing these realities. Some day, some body will use this factual data to get things right for PNG.