When the countries of the Pacific are compared to the cluster of small island states in the Caribbean, the common response by Pacific Islanders is one of annoyance. The title of a recent blog post on the Development Policy Blog by Nik Soni declared emphatically: the Pacific is not the Caribbean. Those familiar with the Pacific note that the Caribbean’s close proximity to the major markets of the US, Mexico and Latin America compared to the Pacific’s great distances marks a defining point of difference. This has huge implications on the viability of export-based economic systems for example.

While agreeing that the Caribbean-Pacific comparison is very limited, with the risk of inciting more annoyance from my Pacific colleagues, I would like to suggest that the countries of the Pacific might have lessons to share with the often-forgotten small island states surrounding the African continent. Most of us will have seen pictures in tourist brochures of Mauritius and Seychelles but few of us will have heard of Cape Verde or São Tomé and Principle.

These small island states of Africa share the tyranny of distance that creates challenges for the Pacific. The distance from Mauritius to Johannesburg (the closest big city) is 3077km; quite similar to the distance between Fiji and Sydney. The Seychelles is more than 2000km from Nairobi (similar to the distance between Tonga and Auckland) and more than 3200km from Mumbai. They also share small populations and limited arable land making dependence on large-scale agriculture a non-viable growth model (table 1).

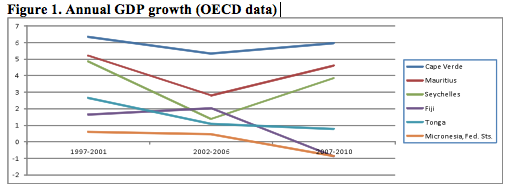

Their geographic isolation and great distance from large, rich-world markets has not stopped these island nations from achieving strong economic growth and charting a path to a strong, sustainable future. Over the past decade and more, the GDP of Mauritius, Cape Verde and Seychelles has grown twice as fast as that of Fiji, Tonga and Federated States of Micronesia (figure 1).

The comparison between Fiji and Mauritius has been made before. Like Fiji, the economy of Mauritius was heavily dependent on the sugar crop in the middle of the 20th century. Unlike Fiji, Mauritius was able to transform itself into one of the most successful economies averaging more than 5 percent GDP growth between 1970 and 2009 and increasing GDP per capita more than tenfold. While the exact reasons for Mauritius’ success have been debated (see for example here [pdf] and here), they are generally seen to include liberal open trade policies, a good education system, a competitive exchange rate and strong institutions. This allowed the country to diversify to become an exporter of textiles and clothes supported by significant foreign investment.

Arvind Subramanian of the Center for Global Development posits a further reason for Mauritius’ success that again has parallels to that of Fiji. Subramanian asserts that Mauritius took advantage of its cultural diversity to build important links to global trading partners especially in India and China. Furthermore, the ethnic diversity demanded the development of participatory political institutions that maintained law and order and stability.

Cape Verde resembles a number of Pacific nations being an archipelago of volcanic islands with few natural resources and little available drinking water. Yet Cape Verde is on track to meet most of the Millennium Development Goals and has dramatically reduced poverty rates. The country has put good governance at the centre of its strategy thus securing substantial investments and loans from various donors to support its tourism and service sectors. It has put its growing budget to good use investing heavily in education. Recently, Cape Verde graduated from being a least developed country to a middle income country.

The Seychelles is one of the few globally to have achieved the Millennium Development Goals targets in poverty, education, gender equity and health. The economy is driven by tourism which accounts for 26% of GDP as well as fisheries including a tuna cannery which is the largest single employer in the islands. There is also the potential of oil and gas deposits in territorial waters. Like the Mauritius, the Seychelles is diversifying their economic relationships and embracing China, India and the United Arab Emirates as key trading partners.

The underlying reason for the success of Africa’s Small Island States is perhaps no surprise. In the Ibrahim index of African governance – three of the top four spots are held by Mauritius, Seychelles and Cape Verde.

The small island states of Africa are not resting on their laurels but are rather charting a clear course forward. Mauritius is now positioning itself as an information technology hub leveraging its linguistic diversity and strong education system. Seychelles is diversifying into renewable energy development and has positioned itself as a leader in environmental conservation.

The experiences of African island countries highlight that economic growth and social stability is achievable for remote, small island states. While the Pacific is unique and will have to find home-grown solutions for its unique challenges, a fuller understanding of the path charted by its African cousins might be of significant worth.

Joel Negin is an Associate of the Development Policy Centre, a Senior Lecturer in International Public Health at the University of Sydney and a Research Fellow for the Menzies Centre for Health Policy.

Many thanks for your post. In relation to comparisons between Fiji and Mauritius, I would like to highlight the importance of trade preferences for the development of industry in both nations.

Subramanium and Roy (2003) found that export manufacturing was the foremost reason for the economic success in Mauritius and that furthermore, preferential access to OECD markets for garment manufacturers in Mauritius (particularly relative to Asian producers with obvious competitive advantages in terms of economies of scale and lower-cost production) was important for growth of the sector. Whilst the multi-fibre agreement, which had been important for Mauritus, ended in 2004, it had allowed Mauritius to develop an industry that could shift to more complex, and more value-added, manufacturing tasks.

I won’t go into the full details here (perhaps another blog piece is in order) but the preferential access to Australian and New Zealand markets for Pacific manufacturing exports, provided under SPARTECA, were also absolutely vital for the explosive growth of garment exports from Fiji from 1987 onwards (though Rabuka’s incentives for foreign investors in the form of tax-free factories probably helped too). While maligned by many as an industry that was ultimately uncompetitive, by the late 90’s 18,000 people worked in Fiji’s garment export industry and it had overtaken sugar exports as the single greatest source of export earnings. Whilst the sector contracted significantly following the removal of subsidies for Australian fabric exporters in 2000 (which had been a key incentive for exporting fabric to often-Australian-owned ‘cut, make and trim’ operations in Fiji, which would in turn re-export finished articles back to Australia under SPARTECA preferences), and the expiry of the MFA (which had guaranteed a quota of Fiji exports to the US) garment exports from Fiji are still worth around FJD 90 million per annum, and the sector could yet remain a longer term prospect (particularly if the restrictive rules of origin requirements of SPARTECA are reviewed).

Sorry to bang on, but the overall point is that meaningful access (and in many cases preferential access) to metropolitan markets has clearly been important for economic growth in both Pacific island countries and the African small island states. A lesson to be drawn is that Australia can do a lot more to improve market access for Pacific exporters.