If recent speeches are anything to go by, politicians believe the best way to sell aid to Australians is to convince them it aids Australia too. It’s an understandable belief, but is it actually, empirically, correct?

In her forceful opening address to the 2017 Australasian Aid Conference, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop framed her talk around seeing, “our aid program through the perspective of Australia’s national interest”. Citing examples of ways in which investments in economic development, gender equality, and security offer mutual benefits for Australia, she stated:

Ladies and gentlemen, there are many ways in which development assistance is building sustainability and resilience in our region and thereby is in Australia’s national interest.

Now this is an important point, too often lost – because support for our invaluable aid program has to come from home, from the Australian taxpayer.

So the Australian taxpayers must support it, and that will come with a better appreciation of its purpose, its intent and the outcomes.

Meanwhile, at the inaugural DFAT Aid Supplier Conference on 17 February, in one of her most animated public presentations to-date, Minister for International Development Concetta Fierravanti-Wells stated,

The question is no longer what we are spending our [aid] money on, it is why are we spending our money, but more importantly what is the direct benefit to Australia.

Adding that,

We need to make it very clear to the Australian public why it is good for their government and their taxes to be used for development abroad.

In short, this requires us to promote our work…What are we doing, more importantly why are we doing it, but very importantly what is the direct benefit to the Australian public, because we need to take the Australian public with us.

We need to make very, very clear to them, why it is in their national interest for us to be spending this year $3.8 billion.

The idea that there’s such a thing as enlightened national interest, and that donors can benefit indirectly from doing good abroad, is not new. (Former UK prime minister David Cameron makes this point eloquently here.) And some recent research provides evidence that giving aid well can, in instances, bring these sorts of benefits to donors.

So the argument is reasonable, but is selling aid along these lines actually necessary to, in Minister Fierravanti-Wells’ words, “take the Australian public with us”?

Not if survey data are to be believed.

Along with the Campaign for Australian Aid the Development Policy Centre placed a series of questions in last year’s Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, a large, academic survey of public opinion that uses the best available methods to gauge Australians’ beliefs.

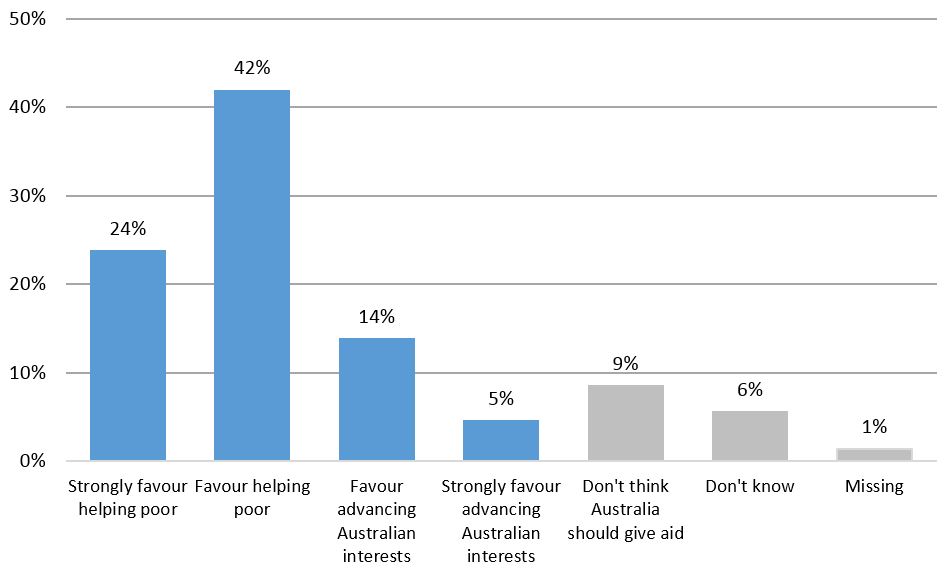

In one question, we asked: Do you think Australian government aid to poor countries should be given primarily for the purpose of helping people in poor countries, or do you think Australian aid should be given primarily to help advance Australia’s commercial and strategic interests?

You can see the results below. Faced with the choice of advancing Australia’s interests or helping developing countries, Australians overwhelmingly chose the latter.

In another question we asked about reasons for giving aid, giving respondents a range of options, including one akin to the enlightened national interest argument Ministers Bishop and Fierravanti-Wells advanced in their speeches. As you can see in the chart below, this option was quite popular. But even so, as the chart shows, most Australians want Australian aid given foremost because it’s a moral or kind act, not because it brings benefits, either directly or indirectly, to Australia.

Thinking now about why the Australian government should give aid to poorer countries, which one of the following comes closest to describing the main reason you think Australia should give aid?

Click here to download the data and background information on these charts [.xlsx].

Most Australians don’t need to see some sort of return to their aid, other than a moral one. This doesn’t mean politicians should never talk about how Australia may benefit indirectly from giving aid well. Different messages may be needed for different audiences. However, the survey data show that most Australians support aid on moral grounds. And if the Australian government wants a message that will resonate with as many people as possible, they should make the moral case for aid.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow and Camilla Burkot is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre.

Thanks for the article – how many people in the survey?

Thanks Julie. Good question.

We provided the sample size in the data download but not in the blog itself. 929 people were surveyed in the first 3 waves of the 16/17 AuSSA. (And it’s the first three waves of data we’ve drawn on in the post).

People were randomly sampled, and the numbers we’ve provided are based on data that were weighted to be nationally representative.

Terence

Terence and Camilla, is it possible that the Ministers you quote aren’t talking to “all Australians” (the demographic that the survey samples), but rather, are talking to the populist right flank of the Australian voting public that currently vote coalition, but are considering switching their support to One Nation (or similar)? I think the proposition that Australians are generally supportive of helping poor people in foreign countries is credible, but the populist right of the Australian voting public probably have a different attitude to foreign aid, and I think the Ministers may be referring more to the latter group, rather than all Australians. What do you think?

Thanks Marcus,

Good point.

For what it’s worth I think (as Tony points out below) that the moral sell (for want of a better term) is probably the most effective one for the wavering and pro-aid parts of the electorate. But I think you’re right that for a particular audience the enlightened-national interest argument may work best (if there are any arguments that work at all — some people aren’t likely to like aid no matter what you have to say about it).

However, the segment of the population likely to be swayed by enlightened-national interest arguments is a minority, which I think means it would be it a mistake on the government’s behalf to talk about benefits to Australia too much. (After all there’s a sort of person likely to be put off by this argument too.)

cheers

Terence

Thanks Chris, a good question

*Looking at correlations*

It’s not quite what you’re after but I looked for a relationship between support for aid and positive views about multilateral organisations and positive views about China and Indonesia in this (older) paper and found a positive correlation: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2672704

There were also questions asked about globalisation in the survey the paper was based on. There seems (with some caveats) to be a positive correlation between people who view globalisation as good for them (or for Australia, which was an additional question) and support for aid. However, the relationship isn’t super robust.

I need to look through our other datasets and see whether we have any surveys in which people were asked about climate change and about aid. That would be an interesting one to look at too.

*Looking at message testing*

This is what I think you’re asking after. I agree it would be an interesting area. It may well be better approached experimentally rather than simply looking for correlations. We haven’t done this yet. If you have good ideas for questions, please email them to us.

Terence

Terence & Camilla, has anyone tested public attitudes to messages around international cooperation to solve common problems (i.e. global public goods) vs messages about aid? I appreciate this would be hard to test – and coming up with compelling messages for the former might be a challenge(!) – but I think it might provide some useful insights into what new narratives may, or may not resonate.

Hi Chris,

We have conducted such research. Last year we commissioned message testing with 1500+ people (cross section of Australians) and dial tested six different messages. The survey was extensive (15min+ per person). We are presenting a summary of that research at three “Transforming our Message” workshops. The Canberra one was last week, but we have the Melbourne and Sydney ones next week. We hope to also present at ACFID conference and other opportunities.

One key finding – national interest arguments (what’s in it for us) are not mobilizing for our core supporters and not persuasive to the middle ground.

Thanks Tony – and sorry I missed the Canberra presentation (I was overseas). I’m definitely looking forwards to talking more about your findings.

Thanks Tony I will try and come along to the Melbourne event. Did you test a ‘common interest’ message (i.e. what is in it for all of us)?

It seems to me that is not quite the same as a national interest argument (i.e. what is in it for ‘us’ and ‘them’)